How to Protect Your Aging Heart

“Man is as old as his arteries.” –Thomas Sydenham

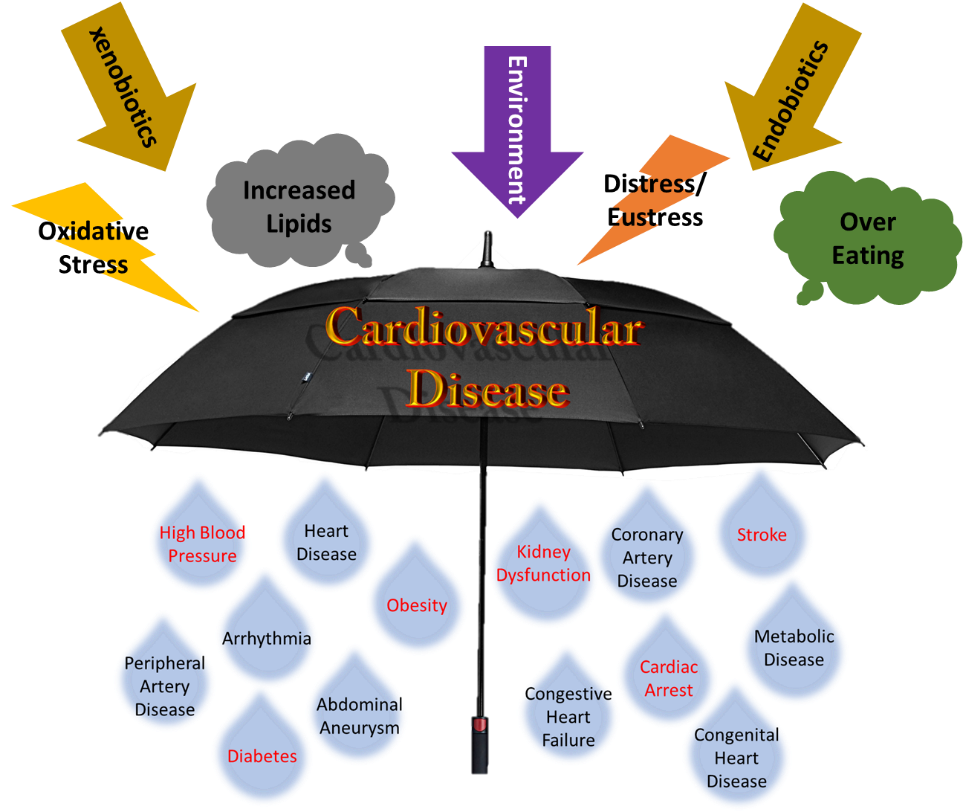

Cardiovascular diseases are commonly associated with unhealthy lifestyles. Do you know that age is a strong predictor of cardiovascular diseases in both men and women? As you grow older, your risks of suffering a heart attack, to have a stroke, or to develop coronary heart disease and heart failure are getting much higher. Ageing research has been evolving rapidly in the recent decades. In the early days, ageing research was mostly focused on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. To improve quality of life in ageing population, other symptoms of ageing including physiological function decline start to capture scientific community’s attention. In AHA Scientific Sessions 2021, a panel of experts and professionals in the field talked about novel strategies to promote healthy vascular aging.

To improve quality of life in ageing population, other symptoms of ageing including physiological function decline start to capture scientific community’s attention. In AHA Scientific Sessions 2021, a panel of experts and professionals in the field talked about novel strategies to promote healthy vascular aging.

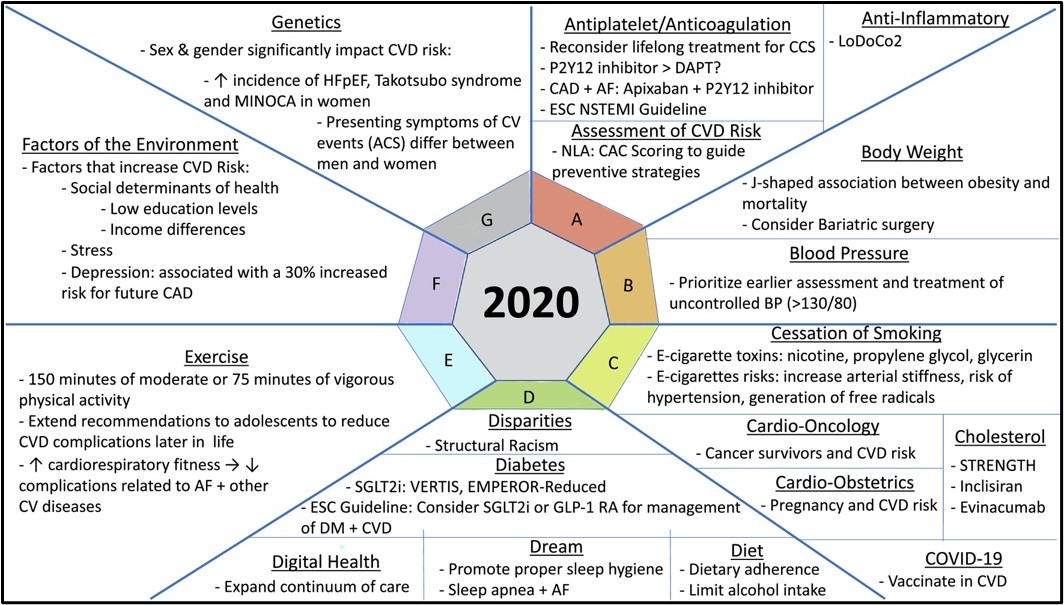

To prevent cardiovascular diseases in aging populations, there are many take-home messages from today’s live session. Dr. Blumenthal from Johns Hopkins University used a simple “ABCDEF” approach1 to highlight the most recent development in cardiovascular diseases management based on most recent scientific discoveries and epidemiological results. Two of the major factors: Diet and Exercise, which are closely associated with body weight management, are further elaborated by Drs. Willett and Donato, respectively.

Dr. Willett is a professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition from Harvard Medical School. He challenged the recommendation of Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). Dr. Willett encouraged the public to focus on evidence-based dietary recommendation, and to evaluate epidemiological studies by using randomized control trials with risk factor, disease incidence and mortality outcomes and prospective epidemiological studies with equal intensity intervention of 12-month and longer. Aside from canonical discussion of dietary recommendation based on health benefits, Dr. Willett raised a pertinent point in environmental sustainability. “How to feed 2 billion people in 2050?” he asked. Climate change is a global crisis and agriculture plays a pivotal role in fighting it. In “the Omnivore’s Dilemma”, Michael Pollan talked about how livestock production is responsible for much of the carbon footprint of global agriculture. The best practice for specific diets to prolong healthy life needs to take into consideration of reducing carbon footprint.

Vascular ageing is comprised of multiple processes including cellular senescence, inflammation and oxidative stress2. Dr. Donato talked about how ageing affects endothelial cell function and habitual aerobic exercise improves endothelial function in men. He also raised an interesting point: this beneficial effect of exercise on endothelial function is sex dependent. More research on sex differences needs to help us understand how to promote healthy ageing. DNA damage is associated with vascular aging. Dr. Shanahan discussed the signaling pathways involving in DNA damage and cellular senescence-associated phenotypes on vascular calcification. Inhibition of DNA damage agents can mediate vascular calcification progression. Can we use DNA damage as a biomarker to detect vascular ageing?

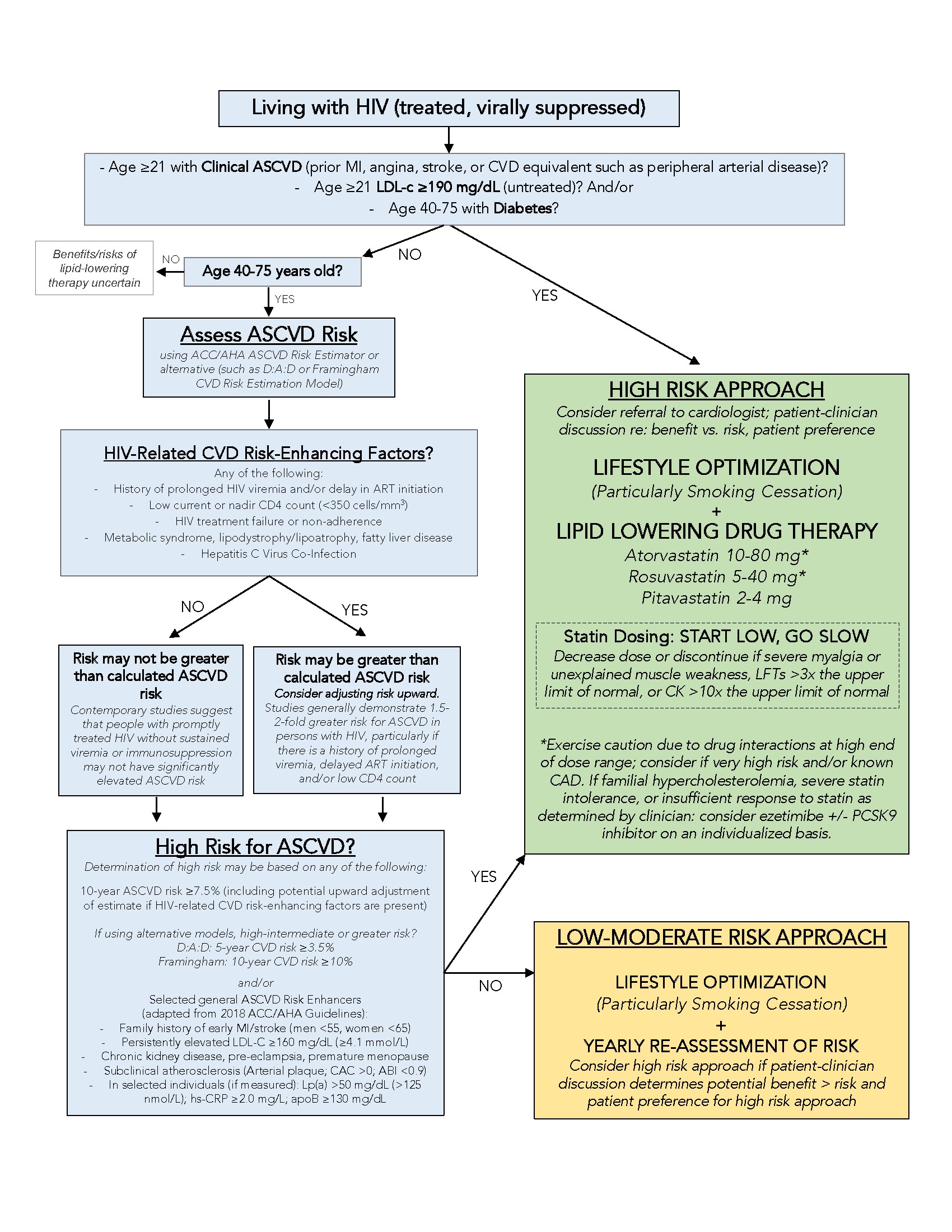

The “One-size-fits-for-all” approach in disease prevention and treatment requires a new perspective. In 2015, Precision Medicine Initiative was launched to accelerate research in disease treatment and prevention by considering individual differences in people’s genes, environments and lifestyles. With the development of next-generation sequencing, risk factors for coronary artery diseases require a modification. Dr. Wolford discussed her research on incorporating genetic backgrounds for disease prediction using polygenic risk scores3. It’s only the beginning of an exciting era using precision medicine as a tool for disease prevention and intervention in cardiovascular diseases.

To protect an aging heart, many approaches need to be implemented. Healthy lifestyles, nice environment and consideration of individual differences are all part of a clue.

REFERENCE

- Feldman DI, Wu KC, Hays AG, Marvel FA, Martin SS, Blumenthal RS, Sharma G. The Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center’s expanded ‘ABC’s approach to highlight 2020 updates in cardiovascular disease prevention. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2021;6:100181.

- Donato AJ, Machin DR, Lesniewski LA. Mechanisms of Dysfunction in the Aging Vasculature and Role in Age-Related Disease. Circulation Research. 2018;123(7):825–848.

- Wolford BN, Surakka I, Graham SE, Nielsen JB, Zhou W, Gabrielsen ME, Skogholt AH, Brumpton BM, Douville N, Hornsby WE, Fritsche LG, Boehnke M, Lee S, Kang HM, Hveem K, et al. Utility of family history in disease prediction in the era of polygenic scores. medRxiv. 2021:2021.06.25.21259158.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

As we know, skeletal muscle mass decreases during the aging process, while cardiometabolic health often declines. A recently published epidemiology study investigated the relationship between skeletal muscle mass and cardiovascular disease in a group of adults (3042 people) without pre-existing cardiovascular risk in a 10-year follow-up study, ATTICA1. After adjusting for various confounders, this study showed a significant inverse association between skeletal muscle mass and cardiovascular incidence (HR 0.06, 95% CI 0.005 to 0.78). Moreover, it showed that people in the highest skeletal muscle mass group had 81% lower risk for a cardiovascular event. The results are quite intriguing. Does decreased skeletal muscle mass contribute to poor heart health or does a failing heart cause muscle mass decrease? It’s hard to figure out the cause and effect without understanding the relationship between skeletal muscle and the heart.

As we know, skeletal muscle mass decreases during the aging process, while cardiometabolic health often declines. A recently published epidemiology study investigated the relationship between skeletal muscle mass and cardiovascular disease in a group of adults (3042 people) without pre-existing cardiovascular risk in a 10-year follow-up study, ATTICA1. After adjusting for various confounders, this study showed a significant inverse association between skeletal muscle mass and cardiovascular incidence (HR 0.06, 95% CI 0.005 to 0.78). Moreover, it showed that people in the highest skeletal muscle mass group had 81% lower risk for a cardiovascular event. The results are quite intriguing. Does decreased skeletal muscle mass contribute to poor heart health or does a failing heart cause muscle mass decrease? It’s hard to figure out the cause and effect without understanding the relationship between skeletal muscle and the heart.