Why Advocacy is Critical for the Future of Cardiovascular Research & Medicine

As researchers and physicians, many of us got in to our professions to push the scientific enterprise further to ultimately help others. We’ve all trained for an insane amount of years and collectively we work as a unit to uncover the intricacies of the cardiovascular system, develop therapeutics and treat patients. We traditionally think of ourselves as researchers or physicians first, but obviously we are all so much more than our jobs. We are also citizens within a really complex system that has been continually struggling to serve all of its citizens equally. It’s no secret that access to affordable health care is currently not equitable within our society. Similarly, there are also large diversity & inclusivity issues within our training institutions for both researchers and physicians.

However, something we don’t think about enough is that our intensive training and experience within these systems has also prepared us to be effective advocates for these issues. We have the opportunity to promote tangible change and some might argue it’s even our responsibility.

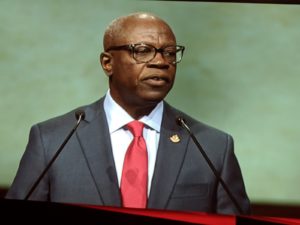

One of the things I really appreciate about being apart of the American Heart Association (AHA) is that this is something the organization doesn’t shy away from. During his presidential address at AHA Scientific Sessions 2018, Dr. Ivor Benjamin gave a heartfelt and determined talk about what the future of the AHA’s advocacy mission looks like. He discussed how supporting local and federal advocacy, early careers and mentoring is key to supporting the future of the AHA – but only 3% of cardiac professionals are African American men and this is something the AHA wants to help change. To help solve the diversity and inclusivity issues within the cardiac field, the AHA is expanding major undergraduate initiatives to fix the leaky pipeline. My favorite part of Dr. Benjamin’s talk was when he urged everyone at AHA18 to get involved in advocacy, not just for our field, but also for our communities. Because this is the key point: in order for our work to have meaning and to be effective, we need to ensure our communities are healthy. We also need to put value to advocacy efforts in our field – this is an essential part of our profession.

Well, this is all great, but how can you get involved? We are all insanely busy; I know adding advocacy efforts can seem daunting. Luckily for all of us, one of the focuses of the AHA for January is Advocacy. Since over 7 million Americans with cardiovascular disease are currently uninsured, advocating for the protection of the Affordable Care Act is something we can all do from our computers right now.

How can you help? (Provided by the AHA newsroom)

- Tell Congress to protect Americans’ access to health care.

- Add your voice: 21 million Americans could lose their health insurance coverage by 2020 if the Affordable Care Act is overturned. Tell Congress to protect Americans’ access to health care.

Looking for more ways to help on other issues?

- The AHA has a great advocacy resource page for to get involved with efforts at the federal, state and community levels with issues regarding health care, tobacco prevention, and healthy lifestyles for kids.

- Sign up here to become part of the AHA’s grassroots network, You’re the Cure, which is focused on advocating for heart-healthy and stroke-smart communities.

- There are many great non-profits around the country focused on promoting science funding, literacy, inclusion, diversity & advocacy – finding the right one for you is key and many of them have already done the legwork by developing toolkits for you to get started in your community.

- Interested in STEM outreach as a way to get involved in your community? The great Marian Wright Edelman said, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Participating in local educational initiatives is one of the best ways to expose kids to what scientists and physicians actually look like (in addition to getting them excited about science). The STEM Ecosystem is a great way to get started; there are local chapters all over the country.

I recently watched the brilliant documentary (I highly recommend it!) about Mr. Rogers, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor”, where I was reminded of his advice many of us take comfort in during intense times.

“When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” – Mr. Rogers

We are the helpers. Its time we use our power to advocate for equity within our field and communities.

Imagine having an annoying pain that you thought was just a pulled muscle. No, I am not referencing that episode of The Resident, a medical drama prime time series aired by Fox, where a young immigrant was having pains in her side and it ended up being a rare cancer. However, I am referring to a real-life hero story about Roxanne (an organ recipient) and Michael (an organ donor). Roxanne had complaints of side pain for about a week, but she continued to work because she thought it was a pulled muscle. She tolerated the pain for about six weeks before she arrived at the emergency room (ER) where she was diagnosed with cardiovascular disease (CVD). She was immediately taken into cardiac care, underwent extensive diagnostic test, and her medical team concluded they could not give her the required treatment locally. Roxanne was transferred to the Cardiac Care unit in Bronx, New York where she was admitted to the hospital for nine days of extensive medical consultations. Upon receiving the diagnostic results, her primary physician approached her with both good news and bad. The bad news was that her heart had started to fail; the good news was she was in a state of stable instability. Roxanne was placed on list to receive a heart transplant as Stat 2.

Imagine having an annoying pain that you thought was just a pulled muscle. No, I am not referencing that episode of The Resident, a medical drama prime time series aired by Fox, where a young immigrant was having pains in her side and it ended up being a rare cancer. However, I am referring to a real-life hero story about Roxanne (an organ recipient) and Michael (an organ donor). Roxanne had complaints of side pain for about a week, but she continued to work because she thought it was a pulled muscle. She tolerated the pain for about six weeks before she arrived at the emergency room (ER) where she was diagnosed with cardiovascular disease (CVD). She was immediately taken into cardiac care, underwent extensive diagnostic test, and her medical team concluded they could not give her the required treatment locally. Roxanne was transferred to the Cardiac Care unit in Bronx, New York where she was admitted to the hospital for nine days of extensive medical consultations. Upon receiving the diagnostic results, her primary physician approached her with both good news and bad. The bad news was that her heart had started to fail; the good news was she was in a state of stable instability. Roxanne was placed on list to receive a heart transplant as Stat 2. Roxanne has changed her activity of daily living to accommodate the dietary habits suggested by her nutritionist in addition to referencing a book she received outlining the things that she could and could not continue to remain healthy. She was adamant about following the instructions that were given because she did not want to risk damaging her new heart. She is now a self-proclaimed foodie although she had no interest in food or cooking to the extent she has developed. She has taken cooking classes and learned more details about mixing spices. Roxanne regularly attends conferences and deliver seminars to assist in her goal of encouraging people become organ donors. Roxanne has become an advocate for people that cannot advocate for themselves. This is an example that all can admire. Michael, real-life superhero, lives on though Roxanne as she goes on a mission to change people’s outlook on organ donations.

Roxanne has changed her activity of daily living to accommodate the dietary habits suggested by her nutritionist in addition to referencing a book she received outlining the things that she could and could not continue to remain healthy. She was adamant about following the instructions that were given because she did not want to risk damaging her new heart. She is now a self-proclaimed foodie although she had no interest in food or cooking to the extent she has developed. She has taken cooking classes and learned more details about mixing spices. Roxanne regularly attends conferences and deliver seminars to assist in her goal of encouraging people become organ donors. Roxanne has become an advocate for people that cannot advocate for themselves. This is an example that all can admire. Michael, real-life superhero, lives on though Roxanne as she goes on a mission to change people’s outlook on organ donations.