RNA, DNA, and COVID-19

As my co-blogger Jeff Hsu, MD, PhD said to me this week, the COVID-19 pandemic has created the ultimate hackathon – the world’s smartest people hyperfocused on the same problem. For this month’s blog, I am outlining few ways that genomics researchers are hoping to advance our understanding of SARS-CoV-2.

Pathogen Evolution and Transmission

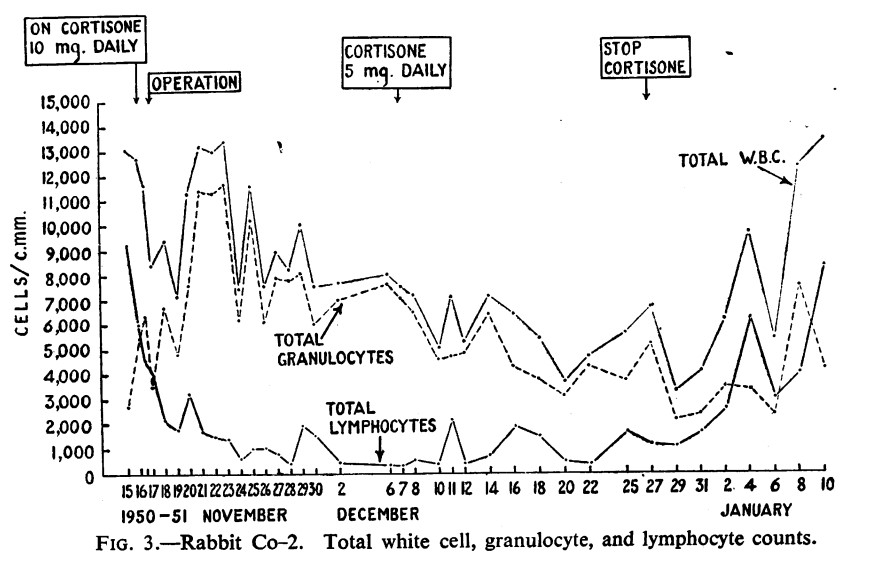

Scientists around the world have pledged to openly share genetic data to aid in the understanding of pathogen spread, and one of these collections of open-source tools is Nextstrain.1 Nextstrain is a database of viral genomes, a bioinformatics pipeline for phylodynamics analysis, and an interactive visualization platform that presents a real-time view of the evolution and spread of seasonal endemic viral pathogens (e.g. influenza) and emergent viral outbreaks (e.g. SARS-CoV-2, Zika, Ebola).1 Over time, viruses naturally accumulate random mutations into their genomes, and these mutations can be used to identify infection clusters that are closely genetically related. Therefore, this can lend insight into introduction events and growth rates. The Nextstrain 2019-nCoV page shows incredible graphical displays of the inferred phylogeny, global transmission events, and genomic diversity over time. At the time of their most recent Situation Report and Executive Summary (dated 3/27/2020), the Nextstrain team had analyzed 1,495 publicly shared SARS-CoV-2 genomes and provided transmission pattern reports for North America, Europe, Central and South America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

For a great introduction to the importance of genomics in identifying the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, check out this Cell Leading Edge Commentary, authored by two of the scientists who were involved in the initial genomic sequencing of the virus.2

Global map of inferred 2019-nCoV transmission from Nexstrain.

Genetic Influences on Disease Outcomes

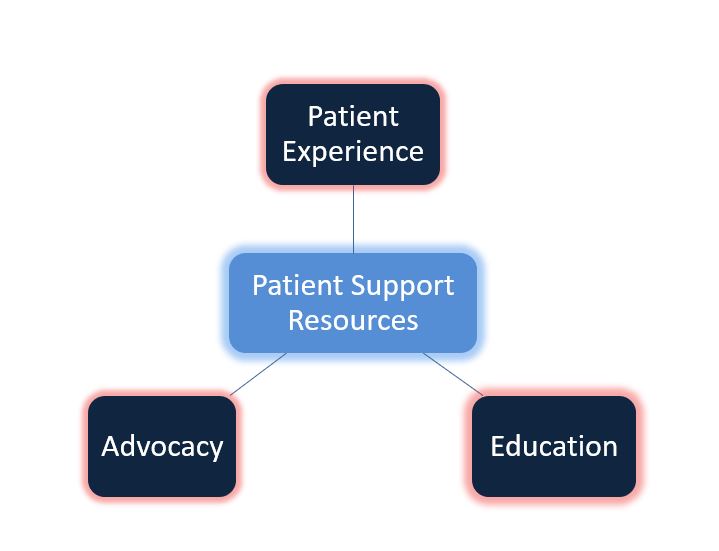

In addition to collecting data on viral genomics, researchers have come together to pool genetic data from patients to try to answer urgent questions regarding the variability in clinical outcomes across patients with COVID-19. To investigate the genetic susceptibility to disease, these researchers will be comparing the DNA of different cohorts of patients with COVID-19, for example, those with serious disease to those with more mild manifestations. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative is one of the largest collaborative initiatives with now over 75 biobanks and studies from around the world listed as partners. Their aims are to facilitate sharing of COVID-19 host genetics research, identify genetic determinants of COVID-19 susceptibility and severity, and provide a platform to share the results to the scientific community. Other large national biobanks like UK Biobank and Iceland’s deCODE Genetics are also planning to add COVID-19-related data to their genomic databases.

The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative at http://covid19hg.org

How can you keep up with the explosion of data in this space? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created an online Coronoavirus Disease Portal, which is a continuously updated database of scientific literature, CDC and NIH resources, and other materials that pertain to genomics, molecular and other precision medicine and precision public health tools in the investigation and control of coronaviruses, such as COVID-19, MERS-CoV, and SARS.

References

- Hadfield et al., Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution, Bioinformatics(2018).

- Zhang and Holmes, A Genomic Perspective on the Origin and Emergence of SARS-CoV-2, Cell (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.035

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

If you are like most medical residents and fellows, you probably do not regularly reflect on the federal government’s role in your graduate medical education (GME). In deciding where to study and train, you may have considered factors like class size, availability of specialty services, and diversity of training environments – but you may not have been aware of the complex influence of the law, federal insurance programs, and payment rates on your medical education. Now, active federal legislation is reinvigorating the conversation regarding GME, the impending physician shortage, our rapidly aging population, and equitable access to health care for all Americans.

If you are like most medical residents and fellows, you probably do not regularly reflect on the federal government’s role in your graduate medical education (GME). In deciding where to study and train, you may have considered factors like class size, availability of specialty services, and diversity of training environments – but you may not have been aware of the complex influence of the law, federal insurance programs, and payment rates on your medical education. Now, active federal legislation is reinvigorating the conversation regarding GME, the impending physician shortage, our rapidly aging population, and equitable access to health care for all Americans. DGME payments cover some of the direct costs of training residents and fellows: stipends, benefits, programming, education expenses, and overhead. IME payments are a bit more complex, so suffice it to say that these payments are intended to pay teaching hospitals’ increased patient costs linked to treating more complex patients. In fiscal year 2016, DGME funds paid to teaching hospitals totaled $3.79 billion, but an estimated total $18.5 billion in direct training costs were incurred. Some, but not all, states supplement funding support with Medicaid, so teaching hospitals are forced to find other avenues to offset these costs.1

DGME payments cover some of the direct costs of training residents and fellows: stipends, benefits, programming, education expenses, and overhead. IME payments are a bit more complex, so suffice it to say that these payments are intended to pay teaching hospitals’ increased patient costs linked to treating more complex patients. In fiscal year 2016, DGME funds paid to teaching hospitals totaled $3.79 billion, but an estimated total $18.5 billion in direct training costs were incurred. Some, but not all, states supplement funding support with Medicaid, so teaching hospitals are forced to find other avenues to offset these costs.1

Earlier this year, bipartisan members of both the United States House of Representatives and Senate introduced a bill called the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2019 (

Earlier this year, bipartisan members of both the United States House of Representatives and Senate introduced a bill called the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2019 ( Last month, over 65 medical associations and specialty societies sent a joint letter to the members of the U.S. Congress strongly encouraging them to cosponsor the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2019, and you can do the same! A quick email or phone call as a voting constituent can go a long way; you can start by

Last month, over 65 medical associations and specialty societies sent a joint letter to the members of the U.S. Congress strongly encouraging them to cosponsor the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2019, and you can do the same! A quick email or phone call as a voting constituent can go a long way; you can start by