During my graduate education years, my understanding and focus on attending conferences was almost exclusively centered on two priorities:

- Learning about the science happening in my area of interest, and the surrounding research that can complement and elevate my present projects.

- Being able to participate (via poster or a short talk) and deliver a useful and potentially distinguished presentation at the conference.

This is pretty much the default priority list for any grad student – not just in biomedical science, but this accurately applies to all academic fields. In fact I’d argue these are basically all that’s needed and required by students being exposed to academic conferences. Professional meeting events come with relatively steep learning curves when students are first experiencing them. Major conferences are (mostly, but not always) held in cities/towns that attendees don’t reside in, so the difficulty of housing, scheduling food, sleep and even clothing choices all come into play.

Unfamiliar surroundings and temporary changes in daily rhythms can lead to elevated stress levels; an effect called allostatic1 load, with measurable biological changes previously reported2, like elevated cortisol and Interlukin-1β levels measured from human salivary samples. Packed conferences potentially strain mental and emotional health, with the cognitive (over)loading that comes from the equivalent of attending a dozen classes (sessions) back-to-back, then doing it all over again the next day and so on, depending on how long the conference is.

These conference days are as demanding as can be, especially for the lesser experienced graduate students. Thankfully, none of what is mentioned here is presently unknown, denied, or ignored. These days enough writing3 exists, reporting all of these observations, sometimes in scientifically quantifiable4 and systematically assessed5 studies. Efforts towards counteracting these difficulties are now discussed, advised, and hopefully even the most ambitious and keen grad students are finding ways to mitigate and avoid negative experiences. Being a scientist in the cardiovascular field, I’ll emphasize two quick notes, extremely obvious, but worth highlighting whenever possible:

- Physical endurance is an undervalued factor in conference attendance, a lot of calories are getting burned moving from session to session, participating in posters/presentations, meeting people and asking questions – so it’s vital to learn, mind and strategize your conference attendance to best fit your physical endurance status

- What you eat matters (always!) and will affect every aspect of your time at the conference (too much/not enough coffee, too much/too little food intake during the conference, healthy vs. unhealthy available options), so again mind and strategize the food/drink variables as part of the overall conference equation.

With repetition and understanding of the general framework of conference proceedings, many of the initial difficulties and trip-ups become learned experiences, allowing attendees to become more comfortable and capable navigators of these unusual few days. This could and does happen sometimes in later grad-school years (senior PhD students, for example), but I’ll focus on the category of attendees that I myself now have become part of the early career professionals and AHA Early Career Blogger. Being in my third year of a postdoctoral fellowship in biomedical research, I’ve been to enough conferences to have a sense of the invisible “skeleton” of conferences. I can identify where the differences between various conferences exist, and where the similarities lie. I’ve learned to gauge how to pack for conferences (if at all possible, avoid checking in luggage! Pack clothing that best represents your professional ambitions. Comfortable shoes are a life saver!), how to navigate the sessions, what to eat and what to avoid. Of course there is no set formula to any of this, trial and error is the most used approach, and sharing experiences can be beneficial (at least that’s my hope in writing this piece!).

I’ll also highlight that for early career professionals, additional priorities/requirements emerge to be added to the original grad-school stage list of goals (namely: learning new information in the field, and fulfilling the level of participation duties offered when registering for the event, like poster or slide presentations). These new aspects are:

- Networking, which I’ll define here as establishing professional lines of communication that can be of benefit in building, and maintaining relationships with others to advance professional goals. This is a valuable advanced priority in conference attendance, but I do want to emphasize that it shouldn’t be a requirement within the early stages of conference participation, since at the beginning, conferences can be overwhelming without the additional stress of having to do expert-level professional socializing!

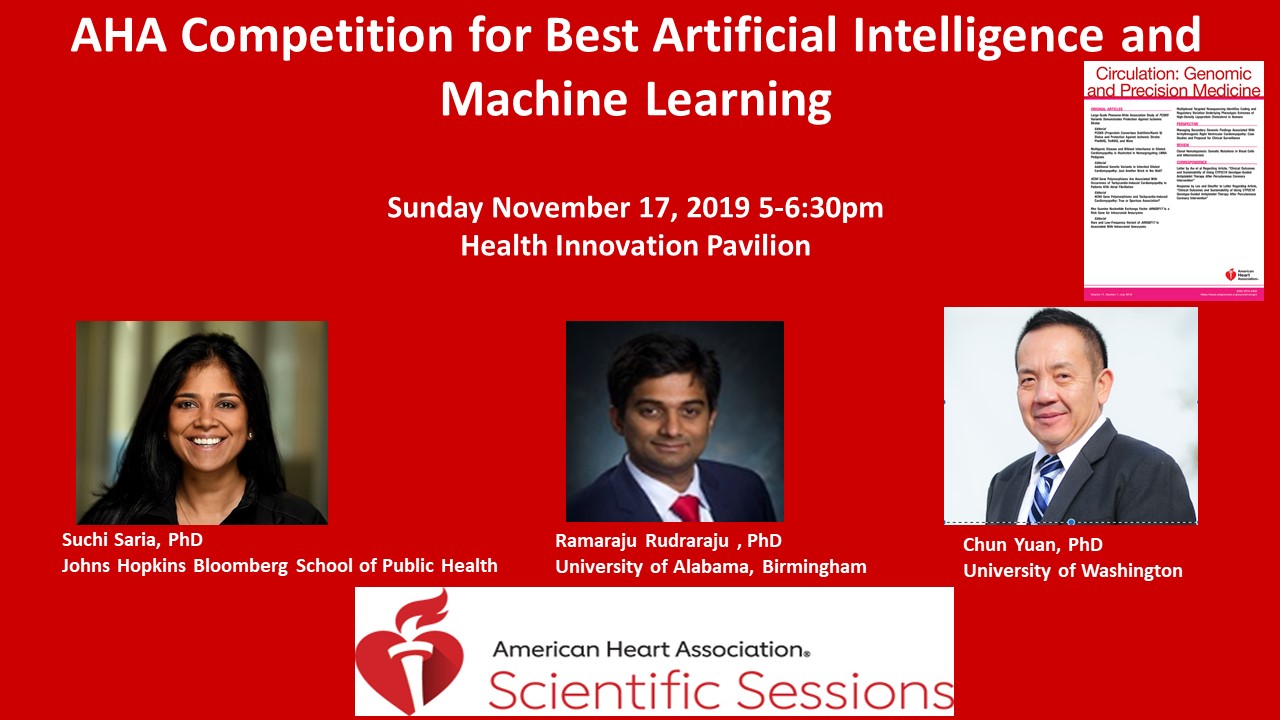

- The newest emerging priority I’ve added to my conference attendance efforts is discovering new elements, sufficiently outside the main field you’re involved in, that can enhance and elevate work/career forward. What I mean by that, being a biomedical research scientist, is seeking sessions in the program that address topics not directly related to: Heart Failure, genomic stability, inflammation, and similar keywords that relate to research my group and I work on. The new elements for me include things like: science communication, social media engagement, scientific advocacy, linking scientists to policy makers; and many other examples of topics that exist around health and scientific research but are not necessarily done in a lab or hospital setting.

Conferences, professional meetings, symposiums, and all types of organized events that occur within professional settings are designed to deliver a large impact to the attendees in a short period of time. Maximizing an individual’s professional development from these settings is key, understanding how to do so requires planning, optimization and gained experience from multiple trials. As with everything else in life, it takes one step at a time.

References:

- McEwen, Bruce S., and Ilia N. Karatsoreos. “Sleep deprivation and circadian disruption: stress, allostasis, and allostatic load.” Sleep medicine clinics1 (2015): 1-10.

- Auer, Brandon J., et al. “Communication and social interaction anxiety enhance interleukin-1 beta and cortisol reactivity during high-stakes public speaking.” Psychoneuroendocrinology94 (2018): 83-90.

- Elfering, Achim, and Simone Grebner. “Getting used to academic public speaking: Global self-esteem predicts habituation in blood pressure response to repeated thesis presentations.” Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback2 (2012): 109-120.

- Lü, Wei, et al. “Extraversion and cardiovascular responses to recurrent social stress: effect of stress intensity.” International Journal of Psychophysiology131 (2018): 144-151.

- Ebrahimi, Omid Vakili, et al. “Psychological interventions for the Fear of Public Speaking: a Meta-analysis.” Frontiers in Psychology10 (2019): 488.

Acknowledgement:

Extended gratitude goes to the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Librarian: Sarah Visintini, MLIS for assistance in compiling primary material sources in this article. Twitter @SVisin

The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.

And to be truly inspired, please add the

And to be truly inspired, please add the