Summarized by Nidhi Madan MD Sarah Rosanel, MD; Cynthia Kos DO, Renee P. Bullock-Palmer MD, Kamala P. Tamirisa MD and Purvi Parwani MBBS MPH. Edited by Marissa Bergman.

Presented by the ACC Women in Cardiology (WIC) Section, AHA WIC Section and Women as One, this webinar highlighted a panel of female cardiologists with leadership roles in the field. The opportunity of gathering 11 female leaders of international Cardiology organizations comes rarely and the webinar was incredibly inspirational. It was co-moderated by ACC WIC Chair Dr. Toniya Singh, MD, Cardiologist at St. Louis Heart & Vascular and AHA WIC Chair, Dr. Annabelle Volgman, MD, Professor of Medicine, Rush College of Medicine;

The webinar focused on providing guidance, empowerment and optimism to women in cardiology through personal journeys and experiences. The presentations equipped attendees with the necessary skills and qualities to more than just survive, but, rather, thrive, during the ongoing pandemic and racial crisis.

Cindy Grines, MD, FACC, MSCAI

President of the Society of Cardiac Angiography & Interventions.

“Accept the situation and have a game plan.”

Dr. Grines began the presentation with her personal journey. She had an extremely successful cardiology career in Michigan for over 25 years. Then, she decided to move, for family reasons, and began a new position as Academic Chair of Cardiology in New York. She was told during the interview process that her focus needed to be 90% on academics, research productivity, mentoring the faculty, and gaining the program a national presence. Over the next 1.5 years, she worked hard towards these goals and exceeded the expectations. Yet, despite going above and beyond in her professional duties, Dr. Grines was terminated from her position without a valid reason – with claims that it was a “business decision” and “trying to merge some roles.” She alluded to how she handled this unprecedented situation, and formulated a game plan. She negotiated a severance package and found her current position, with which she is very happy. Her presentation emphasized the importance of networking and destigmatizing what might feel like a humiliating and isolating situation. Dr. Grines concluded with words of motivation:

“You need to pick yourself up, brush yourself off and get back in the saddle and ride that horse again. The bottom line is change is good and when these things happen to you it’s going to motivate you to do something different and to prove yourself.”

Roxana Mehran, MD, FACC, FACP, FCCP, FESC, FAHA, FSCAI

The Cofounder of “Woman As One.”

“Don’t give up on your goals.”

Dr. Mehran’s presentation started with a bang: “Celebrate Women!” She continued with powerful words, “When we focus on our goals, we can achieve everything and we should never give up on our goals. They are yours, cherish them, fight for it, you will achieve it.”

Dr. Mehran was born in Iran and she dreamt of being a doctor since she was quite young. Amidst the hostage crisis in Iran, her family immigrated to Queens, NY. Despite facing poverty and restarting her life as an outsider, she never lost sight of her aspirations and eventually became an interventional cardiologist. With her determination and strong will, Dr. Mehran was one of the first female fellows at Mount Sinai. She pursued her career and continued her mission to contribute to science and clinical outcomes. As a woman in a male dominated field, she felt the inequalities in interventional cardiology, and she made it her new goal to ensure women are heard. Ultimately, she co-founded “Women As One” to encourage women not to accept inequalities or harassment in any form. As she explained, “You just have to see it all, keep your eye on the ball just like they tell you in baseball and in tennis… and make sure you hit that bull’s eye. Work hard and it will come to you.” She concluded with her favorite quote by Maya Angelou,

“Do your best you can until you know better, then when you know better, do better.”

Athena Poppas, MD, FACC, FASE

President of the American College of Cardiology

“Strategic Leadership & Change Management”

Strategic leadership has never been as important as it is during the challenging times of the pandemic. Dr. Poppas referred to the importance of influential leadership and emphasized that one does not need a title to lead. These times are an incredible opportunity for everyone to step up and contribute. She explained that strategic leadership is not linear, but mostly circular – anticipating, recognizing challenges, interpreting and making decisions, staying aligned but learning along the way. She then shared some of the key tools from her leadership toolbox:

- Authenticity is essential.

- Use influential skills rather than just telling someone what to do – utilize the tools of change management to bring people along.

- Manage conflict and work together.

- Realize one’s own strengths, be honest about those strengths and bounce ideas off friends and allies. Be cognizant about weaknesses with a goal to improve them.

- Put yourself out there and seize opportunities.

Dr. Poppas concluded by reiterating that change management and strategic leadership is a continuum and a continuous cycle of learning. At the same time, succession planning with mentoring and helping others is key, so that there is an entire group capable of replacing you.

Andrea Russo, MD, FHRS

Immediate past President of Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)

“Resilience”

In Dr. Russo’s first week as President of HRS, a controversial topic of Maintenance od Certificate (MOC) surfaced. HRS was looking into ways to create a less disruptive and more customizable educational program and certification. Therefore, HRS put together an MOC Task Force and conducted a member survey assessing the feasibility of other options. Throughout this battle, resilience helped her look into options that would be relevant to the HRS members. The COVID-19 pandemic put the annual HRS meeting in jeopardy. She led the team, which considered the safety of travel and alternate ways to deliver education. Arrhythmias related to the coronavirus needed attention with protocols; how to deliver EP care to patients in the COVID era while also protecting the EP team by reducing their exposure became a priority. To answer these questions, HRS put together a group called the COVID-19 Rapid Response Task Force to collate the major information and provide guidance. There was an outpouring of volunteers and these documents were prepared in record time. This experience emphasized the resilience of a collective resolve from the volunteers who contributed to the HRS staff. Dr. Russo concluded by saying that COVID did jump start the utilization of online educational platforms and digital health to successfully deliver the HRS 2020 content online. She explained that one of the most rewarding experiences of her presidency was the ability to share ideas, work together with leaders from around the globe and improve knowledge.

Christine Albert, MD, MPH, FHRS

President of Heart Rhythm Society

“Embrace Change, Be Creative”

Dr. Albert’s advice is, when one cannot change the adversity, it is important to change gears and embrace the new opportunity. Listening to new suggestions, moving forward and ultimately bringing the group along as a leader are an integral part of being creative. Advances in digital forms of communication in COVID times are one such example of embracing the change. She ended with these empowering words, “Don’t be afraid to forge ahead in adversity.”

Mariell Jessup, MD, FAHA

Chief Science & Medical Officer of American Heart Association

“Believe in your Capabilities”

Dr. Jessup’s presentation focused on how it takes courage to overpower impostor syndrome and its nagging question, “Are you capable?” She pointed to Michelle Obama’s comments as a guiding example: “Am I good enough?” “Of course!” She argued that courage might not be easy to find every moment, and that friends and mentors play an important role against a doubtful mind.

She referred to Eleanor Roosevelt’s challenging life and quoted, “You gain strength, courage and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say to yourself, ‘I have lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.’ You must do the thing you think you cannot do.”

Dr. Jessup offered several more phrases and quotes to empower and remind women that it is vital to focus on courage to lift up mentees. She was reminded of Queen Elizabeth’s quote, “When life seems hard, the courageous do not lie down and accept defeat; instead, they are all the more determined to struggle for a better future.” Another voice of reason she found very relevant is Winston Churchill, regarding sharing courage “I never gave them courage; I was able to focus theirs.” She concluded her presentation on an uplifting note – “Have the courage!”

Michelle Albert, MD, MPH, FAHA, FACC

President, Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC)

“Remembering your purpose”

Dr. Albert emphasized being innovative and creative while also being kind and compassionate in a society facing healthcare disparities. It is important to remember the purpose, when attempting to have an impact. She also emphasized harnessing one’s background to help focus on one’s individual passion and follow that purpose.

Raised by her grandparents, Dr. Albert witnessed hardship and segregation, and she perceived how the socioeconomic background of the patients influenced healthcare. As she explained, “The largest gap in healthcare is in cardiovascular medicine”.

Dr. Albert further highlighted the importance of appropriate support, including key mentorship and faith to overcome adversity. She stressed that being disciplined; bold, collaborative and always thinking outside of the box are key for achieving ultimate professional purpose.

She concluded by warning against transactional relationships or being predatory in the professional setting.

Chiara Bucciarelli-Ducci, MD, PhD, FESC, FRCP

CEO, Society of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (SCMR)

“What opportunities can this adversity bring?”

Dr. Bucciarelli-Ducci believes there are endless opportunities and each challenge simply leads to more opportunities. She is a transformational leader, someone who tries to identify the need for change, create a vision, guide change through inspiration and work collaboratively. She always aspired to be that woman in cardiology and her experience has taught that with change always comes resistance. She stressed the importance of listening to all parties while honing the power of negotiation. She quoted Socrates, in emphasizing the power of a collaborative team, “The secret of change is to focus all of your energy, not on fighting the old, but on building the new.”

Her Italian background, upbringing and world history inspire her tremendously. To Dr. Bucciarelli-Ducci, the COVID-19 pandemic parallels what happened during World War II (WWII). Just like WWII, she believes that this pandemic is creating new ways of thinking, working and connecting with people across the globe.

Sharmila Dorbala, MD, MPH, FASNC

President, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNAC)

“Be Optimistic”

In Dr. Dorbala’s experience, “Optimism is one of the keys to success.” She believes that whether one looks at the glass as half-full or half-empty is a matter of perspective and choice. One can choose to be an optimist and train oneself to focus on the positives, and that optimism gives one confidence to take risks and then becomes contagious.

She provided an example of contrasting optimists and pessimists and how they view the world differently. Optimists see challenges as being temporary, something that can be conquered and used as a stepping-stone to better solutions, whereas pessimists view challenges as insurmountable obstacles. She referenced her research interest in cardiac amyloidosis to illustrate how optimism has influenced her own career. Dr. Dorbala actively chose to be optimistic and stayed in this field despite the hurdles she encountered. She always remained passionate about her field and confident that her hard work would lead to opportunities. She believes that the advances in medicine seen today are because the medical community chose to focus on the potential of the future.

Her overall advice for professional life is to have the integrity to do what is right, irrespective of the consequences, focus on excellence and be passionate about the cause. She reminds us to never underestimate the importance of having an optimistic outlook to gain confidence and to look for opportunities by embracing risks.

Judy Hung, MD, FASE

Incoming President, American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)

“Forget the noise and forge ahead”

Dr. Hung emphasized that during one’s medical career there will be many instances of biases and inequality, intentional or unconscious. She advised that these injustices should not distract one from pursuing their goals. To her, it is important to always stay in the lane. Dr. Hung explained that one could transform anger and sadness into positive energy, and make an impact professionally. Her strongest advice to women in cardiology is to stay focused and not let negative attributes of mental energy sway one away from their focus.

Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, FHFSA, FACC, FAHA

President of Heart Failure Society of North America

“Create Change and acknowledge the ‘never-evers’ ”

In a time that has left everyone grappling with unprecedented personal and professional challenges, how can do you thrive as leaders? Dr. Bozkurt argued, “most advancements come from acknowledgement of the ‘never-evers’”. “You have to face obstacles head on” or else face “stagnation and complacency.” She offered words of wisdom that adversity creates opportunity for resilience to get out of one’s comfort zone and create a meaningful change.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated a constant truth of the profession – doctors are witness to human suffering, but, at the same time, healing. “Do not sanitize suffering…learn from it… and teach the next generation,” said Dr. Bozkurt. She cautioned against disinfecting the truth out of uncomfortable realities. Amongst the suffering and sacrifice lies empathy, humility, and growth.

Dr. Bozkurt cited the story of Marguerite Matisse as a compelling example. Marguerite suffered from severe illness at a young age, requiring a tracheostomy. Despite poor health and a prominent scar, she became a lifelong muse for her father, the renowned artist Henri Matisse. As he once explained, “I don’t remember adversity, I remember resilience.” Dr. Bozkurt hopes that when the world looks back on the current healthcare, economic, racial, and political situations, Matisse’s quote will ring true.

Visit this website for access to this important webinar.

Summarized by Nidhi Madan MD Sarah Rosanel, MD; Cynthia Kos DO, Renee P. Bullock-Palmer MD, Kamala P. Tamirisa MD and Purvi Parwani MBBS MPH. Edited by Marissa Bergman.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

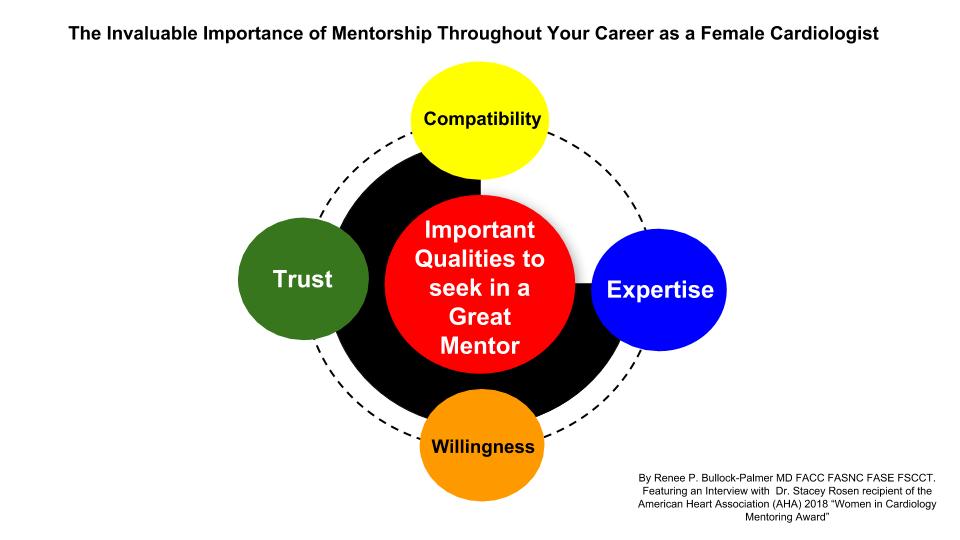

There is an ever increasing need to not only recruit more females in the field of Cardiology, but to also retain many talented female cardiologists in the field. Finding a good mentor and fostering good mentorship is invaluable for many females throughout their career in Cardiology. The Women in Cardiology Committee of the American Heart Association (AHA) values the importance of good mentorship and as such bestows the

There is an ever increasing need to not only recruit more females in the field of Cardiology, but to also retain many talented female cardiologists in the field. Finding a good mentor and fostering good mentorship is invaluable for many females throughout their career in Cardiology. The Women in Cardiology Committee of the American Heart Association (AHA) values the importance of good mentorship and as such bestows the