A new and evolving health struggle for Heart failure patients: COVID-19

It’s safe to say we are not living in normal times. This is Heart Failure (HF) in the time of the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Patients with COVID-19 and preexisting cardiovascular disease (CVD) are at an increased risk of severe disease and death. Moreover, infection has also been associated with cardiac injury such as acute myocardial infarction (AMI), myocarditis, and stress-induced cardiomyopathy leading to subsequent cardiogenic shock (CS) requiring advanced heart failure therapies. There is a bidirectional relationship between viral upper respiratory traction infection(URI) and worsening HF with an increase in hospital re-admission rate as previously noted with influenza. Patients with HF are especially susceptible to influenza-related complications, including acute decompensated HF and secondary pneumonia. Furthermore, HF is associated with greater in-hospital mortality and adverse clinical outcomes. With around 1 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and counting in the US, one would expect an increase in heart failure admissions. Over the past several weeks as the number of COVID-19 admissions increase, the number of patients admitted with heart failure admissions have been at their lowest, which raises the following question: Where are all the HF patients?

We can speculate that people are terrified at home so they are not showing up to the emergency departments. Patients could be slowly accumulating fluids and getting into a decompensated state. On the other hand, being less active, they could also have been experiencing less symptoms. First it was influenza season now overlapping with a COVID-19 pandemic. It would be expected to see an increased number of HF admissions. It is suggested that we might be experiencing the calm before the storm when it comes to HF decompensation requiring hospitalization. The alternative is that social distancing is the remedy that we have long been waiting for to help decrease heart failure exacerbation and hospital re-admissions rates.

On one bright note, during a telehealth cardiology visit follow up with a long-term patient with chronic systolic heart failure known to have been admitted several times during the past year secondary to medication non-adherence, who admits that he has been feeling great. He takes all his medications religiously now, including his diuretics. He states that the fact that he stays home, he doesn’t have to worry about going to the bathroom to urinate so often when he gets out of the house, therefore he doesn’t miss any of his diuretic doses. He is also compliant with diet as he doesn’t eat out as often as he is used to. He admits that he stopped going out to fast food places. This is one very small sample. On the other hand, on another telehealth visit, there is a patient with newly diagnosed Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy and HF with reduced ejection fraction, who is been followed for up-titration of guideline directed medical therapy. It was a challenge to safely increase the dose of his medications without vital signs and avoiding to have the patient physically get to a laboratory to get blood work done. As of now, no major changes were made in the patient current management. Of note, patient did ask about holding angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors because of what he heard from another source. Once more, no changes were made to the medical regimen and it was explained that it has been recommended based on different society guidelines and expert consensus report, to continue with ACE inhibitors1.

COVID-19 times are dynamic and medical information is constantly being updated. This is an ongoing discussion as the clinical data comes in. As the pandemic evolves and more telehealth visit under our belts, we will continue to find out more. Although as our health care system is currently fighting the COVID-19; we must brace ourselves for the aftermath whether our patients are dying at home, or slowly decompensating. Only time will tell. As we are flattening to curve with social distancing, our patients with chronic conditions like HF are waiting at home with so much uncertainties surrounding their current and future medical care. “When life gives you lemon, make lemonade”.

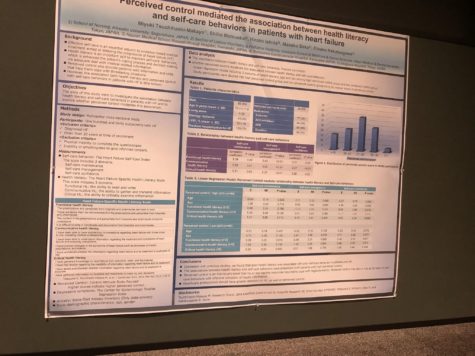

The following suggestions can be useful when taking care of heart failure patients during these unprecedented times. (Figure 1) With COVID-19, we should let our HF patients know although social distancing is essential, they are a higher risk population for a complicated course if infected. It is important to inform them on when to seek medical care, whether it’s to contact a health care provider, call emergency medical services, or go to the emergency department. Although, prevention remains the best medicine. They should take the extra step in precautions and follow the latest recommendations from their local department of public health as we should always remind them of what those recommendations consist of via our telehealth visits. From a cardiologist stand point, it is important to remain available whether it is via email, pager and/or more frequent telehealth visit if possible. If they don’t have a scale and/or automatic blood pressure machines, it should be suggested to obtain them along with a thermometer from their local pharmacies. With a phone camera, it is feasible to assess Jugular Venous Distention, pitting edema. In addition, with weight trends, blood pressure and heart rate, clinical decisions could be made. If available, assessment of data via CardioMEMS can also be very helpful in making medical decisions. Desperate times call for desperate measures. This is too shall pass. If this is the calm before the storm for our heart failure patients, we should be ready when it hits remembering the sun always shines after a storm.

Figure 1. Heart Failure Care Suggestions During COVID-19

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”