Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine

Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) has been declared a pandemic by the world health organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. Since the outbreak, the WHO reported more than 70 million confirmed cases, and 1.5 million deaths globally. In the US, nearly 300,000 lost their lives and currently, we are facing another surge of cases with a record-breaking 3,124 new deaths in a single day last week. Over the past year, scientists, physicians, and pharmaceutical companies did phenomenal efforts to develop a safe and effective vaccine.

Finally, on December 11 2020, The Food and Drug Administration has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Pfizer and BioNTech’s coronavirus vaccine (based on a 17 to 4 vote with one abstention). It is important to note that an EUA is not equivalent to FDA approval. As the latter requires safety data for at least six months. The FDA clearance occurred in a record-breaking time frame for a complicated process that usually takes years. This EUA makes the United States the sixth country to clear the vaccine after Bahrain, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, and the United Kingdom. In this blog, I will review the data behind the EUA.

The study behind the FDA’s EUA was a multinational, phase 2/3, Placebo-controlled, observer-blinded randomized trial. Between July 2020, and November 2020, 43,548 participants (16 years and older) who were healthy or had stable medical conditions underwent 1:1 randomization to receive vaccine or placebo (saline). Of which, 36,523 received two doses (21 days apart) and completed the 2 months follow up. There were 8 cases of Covid-19 with onset at least 7 days after the second dose among the vaccine group and 162 cases among the placebo group. Hence the vaccine was 95% effective in preventing Covid-19. Moreover, among the 10 cases of severe Covid-19 with onset after the first dose, 9 occurred in the placebo group and 1 in the vaccine group.

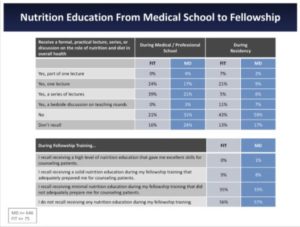

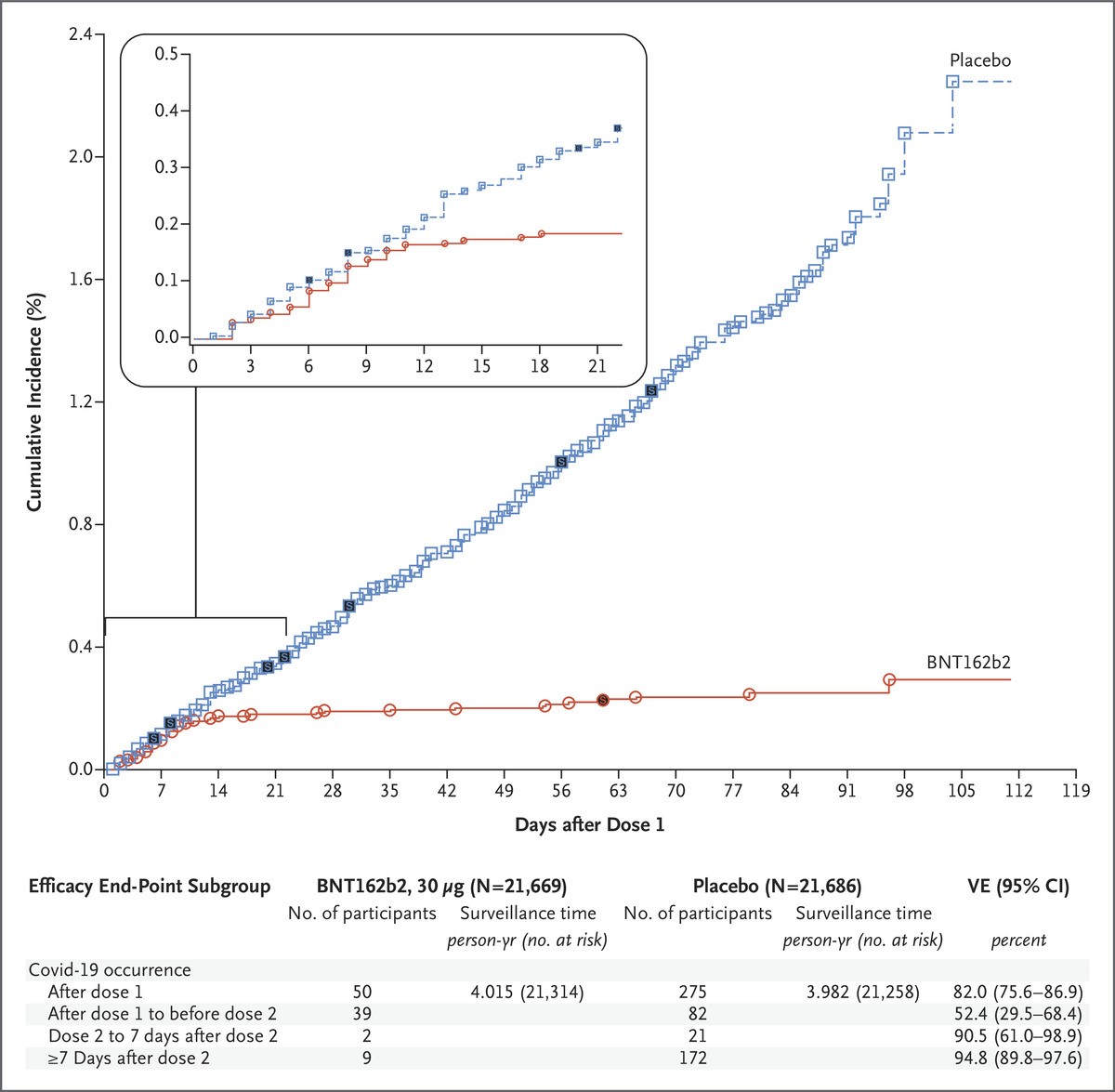

Figure 1: Efficacy of the vaccine against Covid-19 after the First Dose.

Each symbol represents Covid-19 cases starting on a given day; filled symbols represent severe Covid-19 cases. The inset shows the same data on an enlarged y-axis, through 21 days.

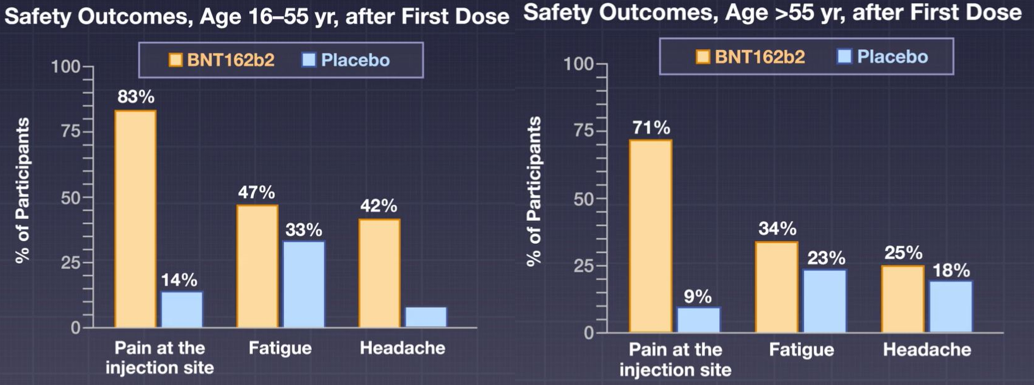

The noted side effects were short-term mild-to-moderate pain at the injection site, fatigue, and headache. The incidence of serious adverse events was low and similar in both groups (0.6% in the vaccine group and 0.5% in the placebo group).

Figure 2: Safety outcomes of the vaccine.

The Vaccine works simply as it contains a small piece of the virus’s mRNA that instructs cells in the body to produce the virus’s distinctive “spike” protein. After receiving the vaccine, the body will manufacture a piece of the COVID-19 virus named spike protein, which does not cause disease but triggers the immune system to learn to react defensively. Given the novel mechanism, theoretically, it carries no risk of infection, as it only codes for a piece of the virus. It is also important to note that currently, it is unclear how long the vaccine will provide protection, nor is there evidence that the vaccine prevents transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from person to person.

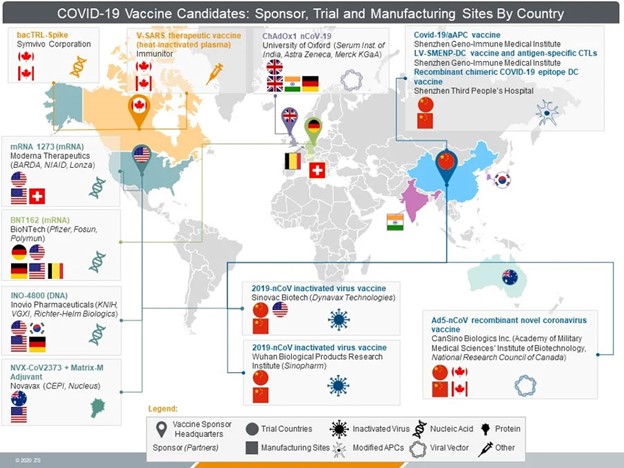

Given the promising results and the EUA, Pfizer is planning on shipping 2.9 million doses over this week and 100 million doses of the vaccine by next March. The pharmaceutical giant has a deal with the U.S. government, under that agreement, the vaccines will be free to the public. Understandably, the distribution will be in phases with the most critical workers and vulnerable people being on top of the list. At this point, strict monitoring of any side effects will be enforced at all sites. Apart from the approved vaccine, Moderna’s vaccine utilized a similar technology and is currently under review by the FDA and could obtain an EUA soon. Other pharmaceutical companies such as Johnson & Johnson, Oxford, and AstraZeneca, are in late-stage trials and their vaccines could be authorized in the near future. This Vaccine is the light at the end of the tunnel which gives humanity hope to reach an endpoint to this pandemic. In the meantime, we must practice social distancing, trust the data, and get vaccinated!

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

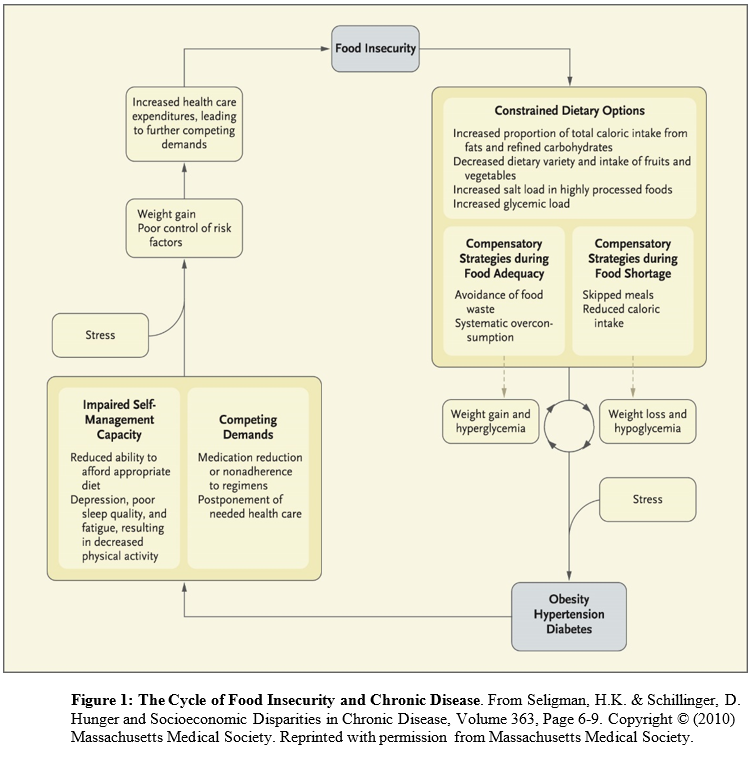

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.