I hope someday we will be able to proclaim that we have banished hunger in the United States, and that we’ve been able to bring nutrition and health to the whole world. –Senator George McGovern

Food. Nothing is more basic to our existence than eating. However, in our modern era of plenty, we often take the presence of food for granted. That is, we take it for granted until we no longer have access to it or it makes us sick.

Food insecurity, when individuals lack access to adequate and safe food due to limited resources, is pervasive in the United States. In 2018, 37.2 million Americans were food insecure and of that, 6 million were children. A recent analysis found that 20-50% of college students were food insecure and hunger affects their ability to learn, be economically stable, and navigate social situations. While food insecurity tends to be higher in rural areas, it affects people of every gender, age, race and ethnicity throughout the United States.

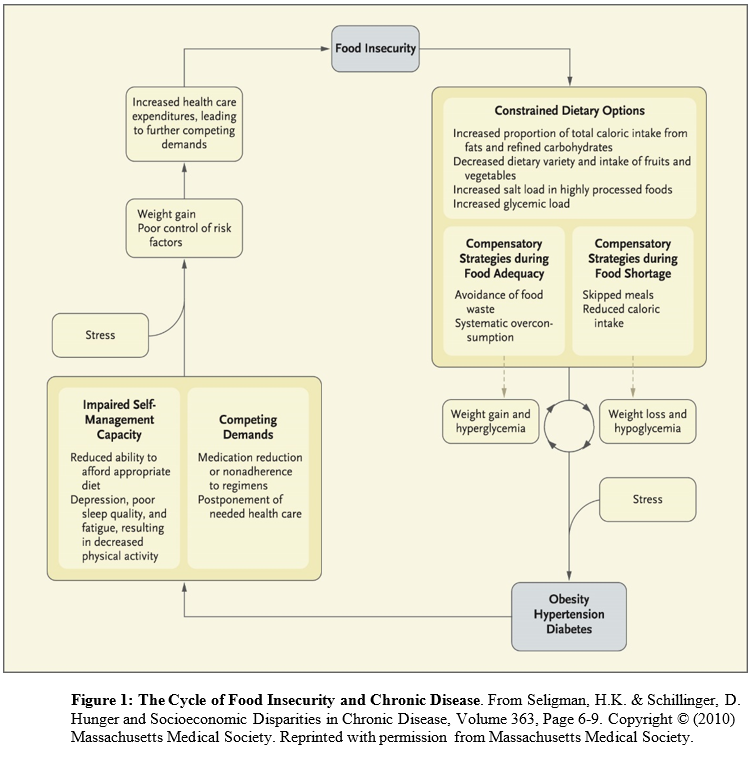

The health consequences of food insecurity are well-described and have a disproportionate impact on cardiovascular health. In children, food insecurity is associated with birth defects, cognitive and behavioral problems, increased rates of asthma, depression, suicide ideation, and an increased risk of hospitalization. In adults, food insecurity is linked to mental health problems, diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. Food insecurity affects health in multiple ways (Figure 1).  Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

As a driver of poor nutritional intake, food insecurity is among the leading causes of chronic disease-related morbidity. As such, there is increasing recognition that for many food insecurity is not behavioral challenge but a structural one. Indeed this is the reason for the creation and continued re-authorization of the supplemental nutritional assistance program (or SNAP) that in 2018 provided $60.8 billion to more than 40 million Americans. SNAP was initially conceived during the Great Depression as a strategy to stave off mass starvation while providing American farmers with a fair price for their surplus agricultural products. It has gone through many legislative and administrative updates since the 1930’s (for a full history, please see Dr. Marion Nestle’s recent review in the American Journal of Public Health) and today remains the 3rd largest, and one of the most effective anti-hunger programs in the United States. Yet, despite its success at reducing food insecurity, today, proposals to reduce the monthly benefit levels and impose restrictions to limit access to SNAP are gaining political traction. If the proposed SNAP reforms were enacted, 2.2 million American households would no longer be eligible for SNAP and an additional 3.1 million households would receive reduced benefits–many of those affected would be elderly and disabled. Thus, the cycle of food insecurity and chronic disease would worsen.

Food nourishes us and provides the sustenance we need to get through each day with our health, livelihood, and dignity intact. While I have outlined the public health case for mitigating food insecurity; it is clear that food insecurity is not just a health issue, or even just a political issue. Above all else, it is a moral issue and one that we that we cannot be on the fence on. We must decide if today, in the richest country on the planet, at its most prosperous time in history, our friends, patients, and neighbors – men, women, and children who are just like us – should be hungry.

If your answer is no, then thankfully there is much that we can do about it. Check back for next month’s blog on strategies that health care providers, neighbors, citizens, and professional associations can do to help address food insecurity in America. In the meantime, please share your experiences addressing food insecurity in your own practice or community with me at @AllisonWebelPhD.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”