As we embark on this new year, we are bound to field questions from our patients (and likely, family members) centered around the most popular new year’s resolution: Eating healthier. Reflecting upon my own answers to these questions in clinic over the years, I realize they have been some combination of:

“Eat smaller portions.” “Eat less meat.” “Cut out soda or juice.” “Don’t eat for 3 hours before going to bed.” “Have you heard of the Mediterranean diet?”

And the basis for my recommendations? While I’m sure my years of medical training were factored in somewhere, I feel like these suggestions were largely based on a combination of my own experiences with managing my nutrition, anecdotes from colleagues and friends, and quite possibly my favorite podcasts.

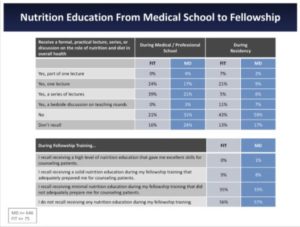

Upon further reflection, though, this is not all too surprising. For all the years that we spend in medical school, residency, and fellowship learning about pathophysiology and pharmacology, we receive much less structured education on nutrition.1 In four years of medical school, one study estimates that the average medical student receives approximately only 19 hours of didactic lectures in total on nutrition, with most of this education focusing on the manifestations of nutritional deficiencies (thiamine, vitamin C, etc.).2 If your recollection is like mine though, 19 hours seems like an overestimation, and it only declines in post-graduate medical training. In a recent study published in the American Journal of Medicine, 31% of cardiologists reported receiving no nutrition education in medical school, 59% reported none during residency, and 90% reported receiving no or minimal nutrition education during fellowship.3

Figure 1: Nutrition Education from Medical School to Fellowship. (From Devries et al.3)

“But we are cardiologists, not nutritionists,” one might say. Yet in the same study, 95% of cardiologists believed that their role is to provide their patients at least basic nutrition information (68.6% believed they should personally provide detailed nutrition information to patients).3 While many of our cardiovascular care teams include dieticians specifically trained to counsel our patients on their nutrition habits, we as cardiologists often find ourselves directly answering these questions from our patients.

Indeed, some physicians have made names for themselves by proselytizing specific diets for their patients. Yet what I find a bit unsettling is the variability of the messages we deliver to our patients when it comes to nutrition. While the AHA provides dietary recommendations we can share with our patients, new diets continue to pop up and gain traction in the headlines, inevitably leading to questions from our patients about whether it is safe for them to adhere to these diets. Notably, (1) intermittent fasting, (2) plant-based or vegan, and (3) ketogenic or “keto” appear to be the diets du jour.

While I personally have experimented with intermittent fasting and a plant-based diet, I am a bit uncomfortable fully endorsing one or the other to my patients, each with his or her own metabolic profile and potential list of glucose-lowering medications. When it comes to diet, more than anything, individualization is key. More so than exercise and medications, diet has deeper roots in the cultural, financial and societal environments in which our patients live. Helping them navigate a healthy lifestyle through these obstacles requires not only more time in clinic but also a deeper, more evidence-based foundation in cardiovascular nutrition.

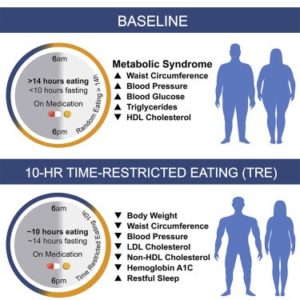

Fortunately, we are entering an era in which we are gathering more evidence in nutrition science. A recent study published earlier this month in Cell Metabolism studied “time-restricted eating” (AKA intermittent fasting with a 10-hour eating window) in patients with metabolic syndrome,4 finding that it had beneficial effects on weight loss and metabolic profile in its albeit small sample size. (Figure 2) Additionally, a New England Journal of Medicine review article published over the holidays highlighted the existing evidence we have, both in animals and in humans, of intermittent fasting on health, longevity, and various disease states (including cardiovascular disease and cancer).5 Importantly, these recent publications and the responses they have elicited in the news and on social media have called attention to the need for more dedicated studies to address the safety and efficacy of specific diets and dietary patterns in our patients with metabolic and/or cardiovascular diseases. Indeed, more clinical trials are underway: a quick search on ClinicalTrials.gov shows that 24 registered clinical trials with an “intermittent fasting” intervention are actively recruiting participants, including the LIFE AS IF trial from the University of Chicago.

Figure 2: Graphical Abstract from Wilkinson et al study on Time-Restricted Eating in Metabolic Syndrome.4

In a prior blog post on “Wearables in Medicine,” I recommended that we consider trialing wearable devices ourselves before counseling patients based on data obtained from them. While I do think our own experiences with diets and dietary patterns may be informative, our personal experiences should not be the sole pillar upon which we base our nutritional recommendations to our patients. Again, individualization is key, and a nuanced approach, factoring in living environments, medications, and metabolic profiles, is necessary.

So what should we do as members of cardiovascular care teams? Well, to provide basic nutrition recommendations to our patients, we can use the AHA Diet & Lifestyle Recommendations. However, we must acknowledge our own limitations regarding the lack of formal training on nutrition during our medical education. As such, my resolution this year is to further my education on nutritional science and attempt to understand how these popular diets may fit within modern cardiovascular disease management. To achieve these goals, I will:

- Read: Some books recommended by my attendings that I plan to read include The Obesity Code by Jason Fung, MD and The Plant Paradox by Steven Gundry, MD. Additionally, for those interested in learning more about the role of a “keto” diet in cardiology, the ACC.org Sports and Exercise Cardiology section recently published a series of high-yield, informative articles (Link 1 and Link 2).

- Collaborate: We have a dietician in our cardiovascular care team with whom I regrettably had not spoken directly with until recently. I previously had just referred patients to her, but I did not necessarily know exactly what advice she was giving to our shared patients. Opening and maintaining this channel of communication is essential to delivering a consistent message from our team.

- Ask: I am now making it a habit to include a simple question in my clinic encounters: “How’s your diet?” I have found the open-endedness of the question to be quite enlightening, often helping me to uncover a new aspect of the world my patient lives in and their own perspective on how their nutrition impacts their health.

I would love to hear your input on this topic. What do you feel our roles are in nutrition counseling for our patients? What are reliable resources to learn more about this topic? How can we be better at delivering appropriate nutrition information to our patients? Please reach out to me on Twitter (@JeffHsuMD) with your thoughts and ideas.

References:

- Devries S, Willett W, Bonow RO. Nutrition Education in Medical School, Residency Training, and Practice. JAMA. 2019;321:1351–1352.

- Adams KM, Butsch WS, Kohlmeier M. The State of Nutrition Education at US Medical Schools. Journal of Biomedical Education. 2015;2015:357627.

- Devries S, Agatston A, Aggarwal M, Aspry KE, Esselstyn CB, Kris-Etherton P, Miller M, O’Keefe JH, Ros E, Rzeszut AK, White BA, Williams KA, Freeman AM. A Deficiency of Nutrition Education and Practice in Cardiology. Am J Med. 2017;130:1298–1305.

- Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, Lo H, Fakhouri S, Shoghi A, Wang X, Fleischer JG, Navlakha S, Panda S, Taub PR. Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2020;31:92-104.e5.

- de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2541–2551.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.