Building an academic portfolio during medical training: Part 3 – The art of reaching out

A year ago, I started a blog series about how to build an academic portfolio during medical training. After the first 2 blogs, COVID-19 hit us hard, and I felt the need to switch gears to address more pressing issues. Now that things are starting to finally move in the right direction, I thought it would be a good time to pick up where we left off.

In Part 1, I discussed why I believe that it is important for medical students and trainees to consider research collaborations outside their own institutions, and what types of research studies can be performed using this type of collaboration between young researchers. In Part 2, I expanded on the different ways you can find established multi-institutional teams of young researchers.

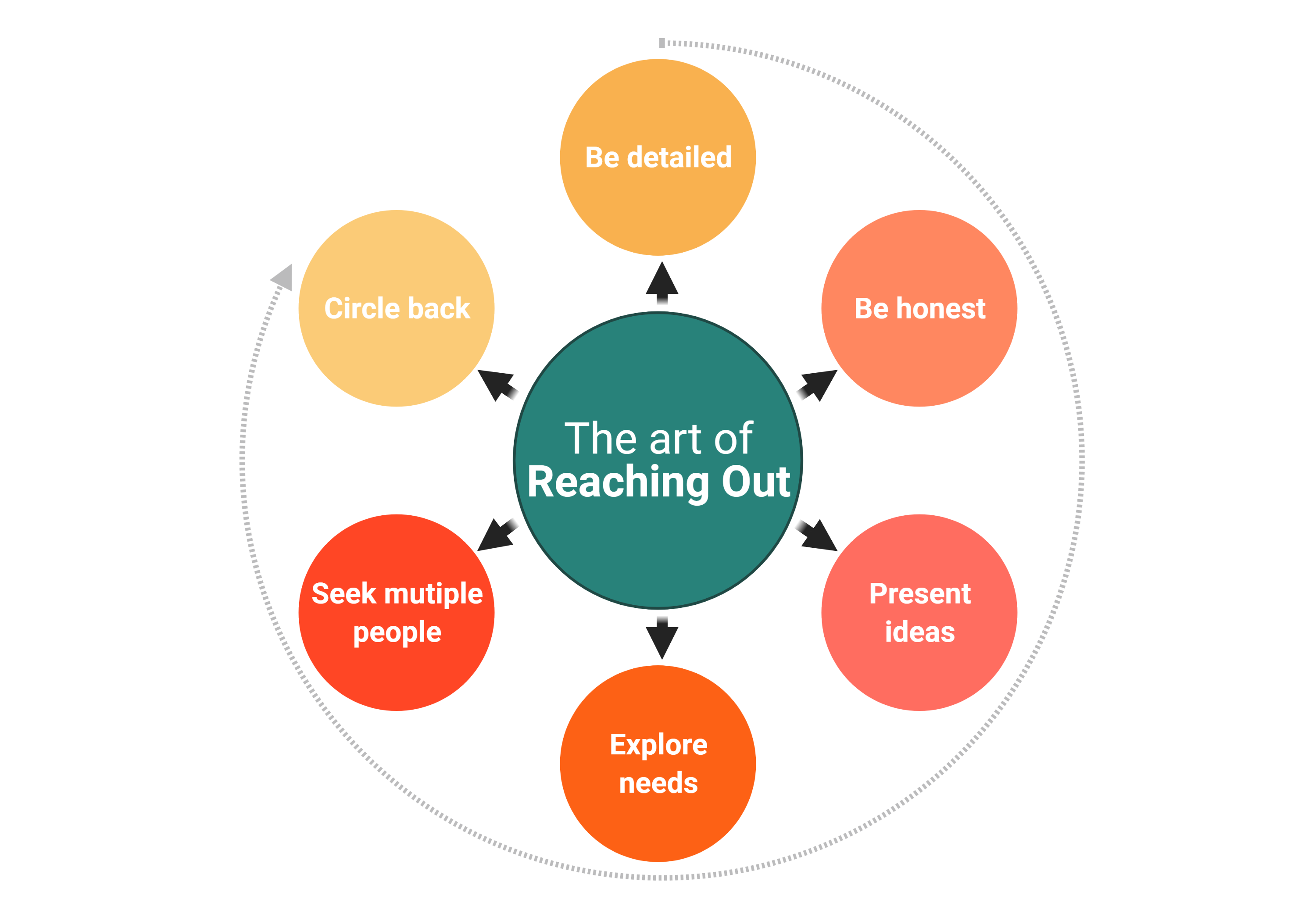

Once you have decided on the researchers that you would like to collaborate with and join their established teams, the next logical step in this process would be to reach out. What is the best approach to use when reaching out, and how can you maximize your chances of success? The following tips may help you achieve this (Figure*):

- Be as detailed as possible. When reaching out, it is essential that you provide as many details as possible: who you are on the professional level (level of training, career plan, etc..), what area of research you are interested in, how novice or advanced you are in the field of research (prior experiences) and what research skills you possess (basic data collection, literature review, statistical knowledge, experience with particular software or database, etc..). The more details you provide, the more likely it that you will receive a favorable response to your request. It also ensures that you join a team that constitutes the best fit for your career goals, and increases the likelihood of this collaboration being productive.

- Be honest. As much as it is important to present yourself in the best possible way, it is even more important, to be honest about what you are able or not able to do, and what you are willing to learn. One of the crucial aspects of collaboration is reliability.

- Don’t be afraid of presenting ideas. If you happen to have some research ideas that you would like to pursue, don’t be afraid of bringing them up on your first contact. You don’t have to provide all the details of what you have in mind, but simple broad lines about some of the areas that you would like to explore may help the person you are contacting in evaluating the utility of potential collaboration.

- Ask about what the team needs. If you are really serious about joining a specific research team, it may be a good idea when you first reach out, to inquire about the skillsets that the team is currently looking for in a collaborator. This not only shows how dedicated you are but increases the likelihood of having a productive collaboration.

- Reach out to more than one team/ person. Research is a very dynamic process, and at any given time a certain team may or may not have an ongoing project with room for additional collaborators. Therefore, reaching out to more than one team is a reasonable approach to avoid a long waiting time before embarking on your first project.

- Circle back. For the same reason mentioned in the prior comment, it is common that you will receive a response like “we would be happy to collaborate, but we don’t currently have a new project for you to join”. Don’t take this as a polite rejection, because it usually is not. Circle back in a couple of months and ask nicely if the situation has changed. In the meantime, you may use tip #4 to make use of the waiting time in a way that shows dedication and improves your portfolio.

Importantly, keep in mind the general rules for teamwork. As much as teams are looking for someone who is valuable and resourceful, they are also looking for someone who is easy to work with. Being professional, collegial, hard worker, flexible and enthusiastic always goes a long way!

Figure created with BioRender.com