#COVID-19: Universal Mask Policy, Universally, Now.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has wrought havoc in major American cities over the past few weeks, particularly in New York City, a common refrain from health care workers (HCWs) on the front line continues to be: “Get Us Personal Protective Equipment (#GetUsPPE).” Yet intertwined in this tragedy of a gross undersupply of PPE has been the problem of mixed messages about the level of PPE that should be used by HCWs, which stemmed from dynamically changing recommendations from the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

Ultimately, the current CDC recommendations, which advise the use of surgical masks when with a symptomatic COVID-19 patient and N95 masks only during aerosolizing procedures, were borne primarily out of an anticipated shortage of PPE, and these recommendations differ from earlier ones that recommended N95-level masks whenever with a patient with suspected COVID-19. Justification for this effective reduction in PPE levels stemmed from the CDC’s thought that COVID-19 is primarily spread via droplet transmission.

In light of this CDC guidance, many hospitals implemented policies that similarly aimed to preserve PPE supply, anchoring on the notion that COVID-19 is transmitted by symptomatic patients via droplets. Many of these policies restricted hospital staff from wearing masks outside of patient rooms, and ultimately led to numerous reports of staff (including house staff trainees) being reprimanded for doing so.

Yet as hospitals in countries like Italy and Spain and in major American cities such as Boston are experiencing alarming numbers of their HCWs test positive for COVID-19, it is crucial for us to reassess whether our current PPE policies are adequate to protect HCWs from infection and to prevent nosocomial spread. Indeed, prominent academic medical centers such as Partners Healthcare, University of Pennsylvania, New York Presbyterian, and University of California San Francisco (UCSF) have already adopted a “Universal Mask Policy” to help address this vital issue.

In order for us to more effectively contain the rapid spread of COVID-19 in our communities, I strongly believe that all hospitals should adopt a Universal Mask Policy, in which hospital staff are required to wear surgical masks in all areas of the hospital. This step is crucial for the safety of our team members, our colleagues, and our patients.

My belief stems from the following:

- Precedent from countries with effective control: On March 18th, the American College of Cardiology held a joint teleconference with the leadership from the Chinese Cardiovascular Association, which included a section on recommendations from their physician leaders on how to adequately control COVID-19 spread at our hospitals in the U.S. They strongly urged us to wear surgical masks in all areas of the hospital, and they also used N95 masks during all encounters with patients with suspected COVID-19. They felt these measures were pivotal in their ability to protect their staff members and control the rampant spread of the virus throughout their hospitals. Further, the Director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. George Gao, told Science that it is a “big mistake” that people in the U.S. are not wearing masks everywhere in public, let alone not wearing them everywhere in the hospital. Similar public masking policies are in place in South Korea, Japan, and Singapore, where COVID-19 disease spread has also been more effectively controlled.

- Likelihood of asymptomatic spread among HCWs in the hospital: It is becoming increasingly clear in the literature that a large portion of the disease spread is from asymptomatic individuals (Li et al, Science, March 16, 2020; CDC MMWR March 27, 2020), with a long incubation time of 5 days median (Lauer et al, Ann Intern Med, March 10, 2020). Hospital staff, who are only advised to stay home from work if symptomatic, may still present to work asymptomatic but infected and contagious. Without at least wearing a surgical mask throughout the hospital, we are at increased risk of spreading infection among each other.

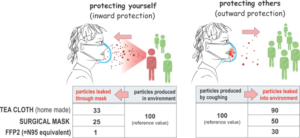

- Transmission by talking: By the nature of our work, we are not used to routinely standing 6 feet away from each other in the hospital as we communicate; in a small Twitter survey, >60% of respondents said that #SocialDistancing is not currently practiced in their hospital. Further, we are all touching common surfaces (e.g., keyboards, computer mice, phones) that will inevitably carry droplets that are inevitably spread from unmasked mouths when we talk. While surgical masks are not the perfect solution to filter out the droplets emitted from our mouths when we talk, cough, or sneeze, they undoubtedly reduce emission into the ambient air around us (Figure 1) and should reduce the likelihood of asymptomatic hospital staff from transmitting infection among each other and to our patients.

Figure 1: Two-way protection provided by masks (from Medium blog post by Sui Huang, MD, PhD at the Institute for Systems Biology)

In summary, I urge all hospitals to implement a Universal Mask Policy to account for these data and expert recommendations. As mentioned above, the lack of a clear, effective message has led to conflict between care teams, leading to discord at a time when unity is so critical. Although no randomized clinical trial has yet to show that a Universal Mask Policy is the most effective way to reduce nosocomial transmission of COVID-19, the “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

When there is enough reason to believe that a Universal Mask Policy should help to protect our staff and patients, we need to err on the side of safety when the consequences are life- and livelihood-threatening. While anticipated mask shortage is clearly an issue, the remarkable resourcefulness, philanthropy, and ingenuity of our communities will come through.

In the meantime, we need a Universal Mask Policy to protect us. We need a Universal Mask Policy to unite us. We need a Universal Mask Policy now.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”