Smallpox to COVID-19: We’ve come a long way!

The history of humankind has never witnessed an infectious agent deadlier than Smallpox. It is thought to have first appeared in Asia or Africa thousands of years ago, before spreading to the rest of the world. This virulent disease was causing hundreds of thousands of deaths each year during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries in Europe alone; and when Europeans brought it to Mexico in the 16th century, it killed nearly half of the previously unexposed Aztec and Inca population in less than 6 months.1,2 In the early 1700s, Lady Mary Montague, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey, and a disfigured Smallpox survivor, was fascinated by the smooth skin of the ladies at the famous Turkish Baths. A face with no scars was a rare sight in Smallpox-devastated England at the time. “The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless, by the invention of engrafting”, she wrote home in her notable letter.3 She had witnessed the primitive form of vaccination, which was then called inoculation. Turkish mothers would gather their children at Smallpox parties, where an old lady would tear the skin of healthy kids and smear a small sample of the virus (typically from a recently infected child). The kids would then develop a mild form of illness that recovers with no scarring and gives them long term immunity. Lady Montague used this technique to protect her son and has been credited for bringing this historical discovery back to England and advocating for its widespread use despite major opposition from the British medical community at the time (Figure 1). Subsequently, in 1796, Edward Jenner developed the much safer technique of vaccination using Cowpox instead of the Smallpox virus.4 Two centuries later, Smallpox was completely eradicated!

Figure 1: The painting Lady Mary Wortley Montagu with her son, Edward Wortley Montagu, and attendants attributed to Jean Baptiste Vanmour (oil on canvas, circa 1717). © National Portrait Gallery, London: NPG 3924.

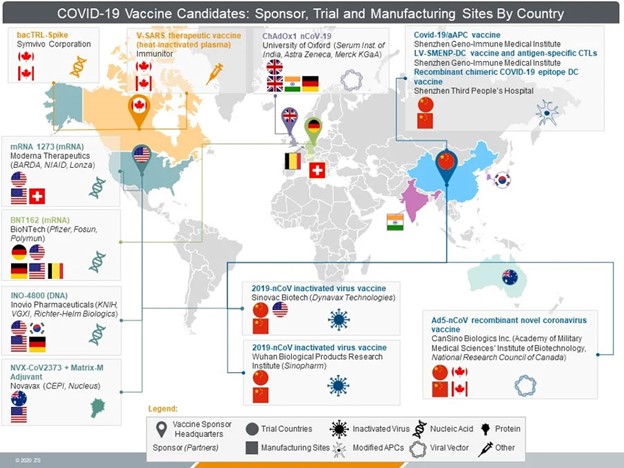

What is most remarkable about this story is that the practice of Smallpox inoculation was introduced in Europe only in 1721 by the relentless efforts of a concerned and enlightened mother, despite being successfully used in Oriental countries such as China, India, and Turkey for centuries. In other words, one half of the globe was deeply suffering from an illness that killed millions of people over the years, while the other half held the secret to its prevention. And it was only when knowledge was exchanged between the two halves that humanity finally defeated one of its deadliest historical enemies! There has never been a better moment to relive and celebrate the magnificent product of worldly human collaboration than these days, as people around the globe started receiving their first doses of COVID-19 vaccines. A deadly virus that took the world by surprise and killed more than 1.5 million people, now, only a year later, has more than one vaccine with proven efficacy. It is amazing how far we have come along since the times of Smallpox! The obvious difference is the power of science and research, yet, another big and equally important difference, is how well connected our world is right now. This unprecedented connection is what allowed us to have a global response to this pandemic and unite our efforts to create a solution (Figure 2). Two Turkish immigrants develop a technology in the labs of a Germany-based biotech company to be quickly adopted by an American Pharmaceutical giant, which tests it and subsequently mounts a large-scale distribution process around the world —among other fascinating stories. As much as we seem deeply divided nowadays, due to political and ideological differences, in fact, over the history of humankind, there has never been a time where the world population was more united! Maybe we clearly see our major differences simply because we have never been this close! And our closeness and continued collaboration are what will get us through this! It is too early to declare victory, and things are far from perfect, but it’s a good time to pause and appreciate our progress!

Figure 2: The global effort for COVID-19 vaccine development.

Image credit: Judith Kulich, Cody Powers, Amit Pangasa, Kristyn Feldman, Parul Rewari and Samaya Krishnan. COVID-19 vaccines: Who might win the race to the global market? Published May 13, 2020. Available online on: https://www.zs.com/insights/covid-19-vaccines-who-might-win-the-race-to-the-global-market

References:

- Hopkins DR. The greatest killer: smallpox in history. vol. 793. University of Chicago Press; 2002.

- Razzell P. The conquest of smallpox: the impact of inoculation on smallpox mortality in eighteenth century Britain. Caliban Books, 13 The Dock, Firle, Sussex BN8 6NY; 1977.

- Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, “Lady Mary Wortley Montagu on Small Pox in Turkey [Letter],” in Children and Youth in History, Item #157. Available online: https://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/items/show/157 (accessed December 27, 2020). Annotated by Lynda Payne

- Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0521732567; 2013.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”