Afraid of What’s in Vaccines? Here Are 5 Things You Ingest or are Exposed to Everyday Without Thinking Twice About Their Effects on Your Body and Heart Health

The American divide regarding the COVID-19 vaccine is a passionate topic for everyone. This article is not intended to prove to readers why getting vaccinated for COVID-19 is safe but to provide some insight on the daily decisions we don’t think twice about that have both theoretical and established health consequences.

- The beef you eat and the milk you drink: Many farm-raised cattle are injected with artificial growth-promoting hormones such as oestradiol, progesterone, testosterone, zeranol, trenbolone and melengestrol to promote rapid meat production. Recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH) is a genetically-engineered synthetic hormone used to increase milk production in cattle, which then communicates to your liver to increase the production of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1). Although no systemic studies have directly researched the health effects of these hormones in the body, associations with DNA damage, infertility, premature puberty and risk for breast, prostate, colon, and lung cancer have been found retrospectively1,2.

- Ultra-processed foods: How often are you eating chips, bagels, pizza, soda, and other highly-processed food items without thinking twice about how they are manufactured? Based on the NOVA system classification, ultra-processed foods go beyond the addition of salt, sweeteners, or fat and include artificial flavors and preservatives that increase the shelf-life in your kitchen cupboards, preserve the texture of foods and increase their palatability to leave you craving for more. More and more studies are being published linking these foods to heart disease, heart attacks, and death from cardiac causes3.

- Aspirin, Tylenol, and Ibuprofen: You likely reach for these common analgesics in your cabinet when you have pain, inflammation, or fever to alleviate the symptoms you are suffering from. However, there are risks and rare side effects associated with taking these drugs that include serious allergic reactions, kidney damage, bleeding, heart attacks, and stroke4. This is not meant to scare you into never taking these medications but to bring to light the many decisions we make that are more likely to benefit us rather than harm us.

- Air pollution: How often do you grab your smartphone to check the air quality for the day? If the quality is less than ideal, how often does that impact whether you go outside? Poor air quality has been associated with heart disease, long-term respiratory problems, stroke, and low life-expectancy5,6. However, the benefits of staying physically active outside, experiencing life events, socializing to improve mental health, and anything else that provides meaning in our lives by being outside likely outweight many of these risks.

- The sun: Everyday, UV radiation from the sun and our atmosphere produce reactive oxygen species that cause direct DNA damage. This can lead to skin aging, skin cancer, and eye damage. Despite these risks, the benefits the sun provides to our planet and existence outweigh the risk and allow us to appreciate the positives7.

Every decision we make involves a conscious or subconscious risk assessment rooted in our values. As physicians, we are committed to providing medical advice based on whether the benefits outweigh the risks for our patients. While I can and will validate your concerns and fears, I hope that in the future you might consider seeing the forest for the trees.

References:

- https://www.jswconline.org/content/68/4/325

- http://ifrj.upm.edu.my/25%20(01)%202018/(1).pdf

- https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.047

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12325-019-01144-9

- https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.5487/TR.2014.30.2.071.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1875213617301304

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13273-017-0002-0

“The views, opinions, and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness, and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke, or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

I know, we have to fit so much into each patient encounter that trying to fit in one more thing seems impossible. But a quick, simple strategy is to administer the

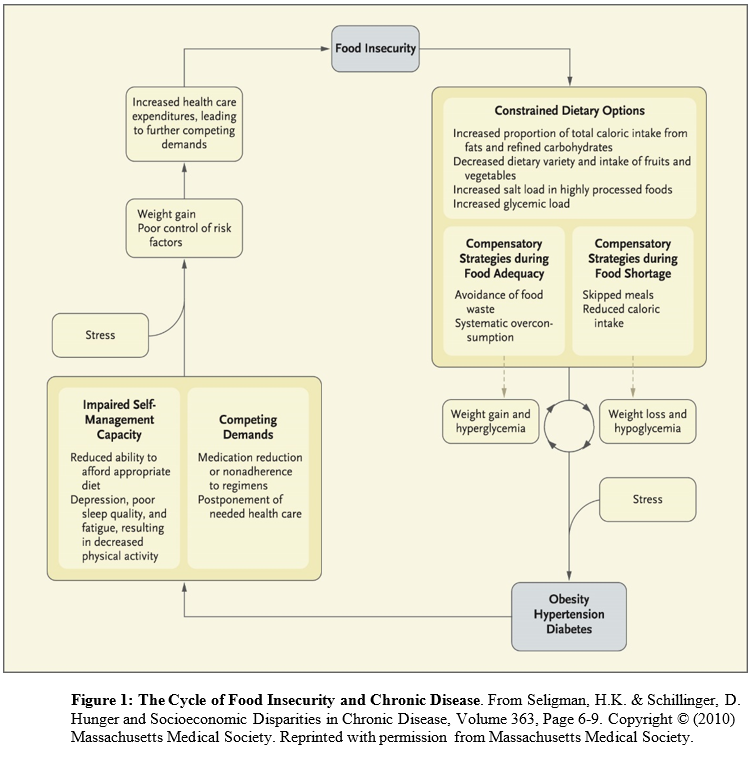

I know, we have to fit so much into each patient encounter that trying to fit in one more thing seems impossible. But a quick, simple strategy is to administer the  Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.