The pursuit of Ideal cardiovascular health: It’s never too LATE! But the earlier, the better!

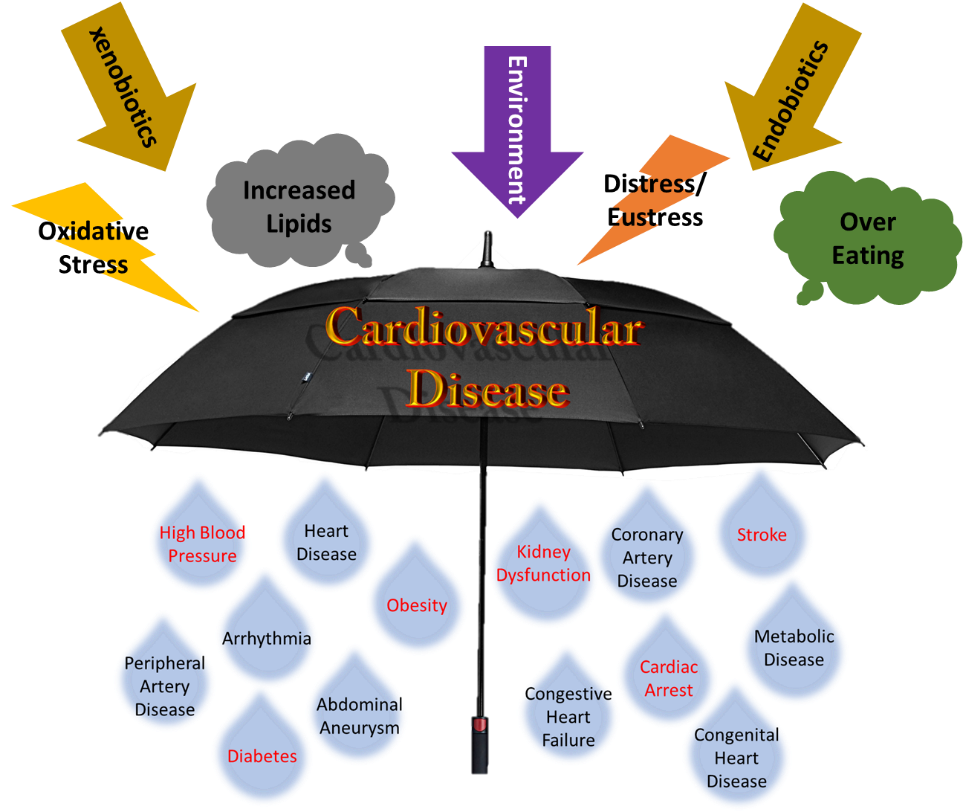

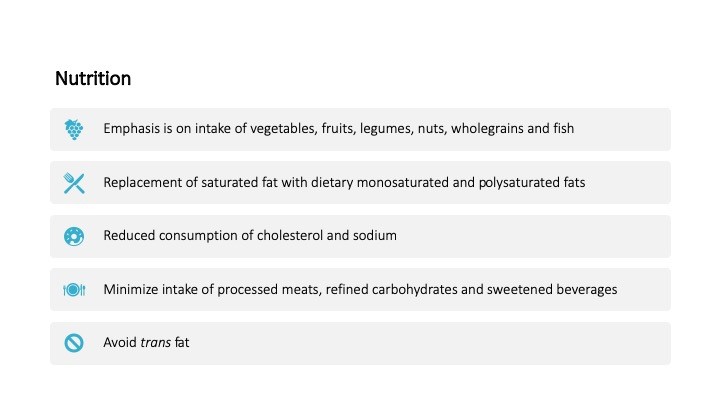

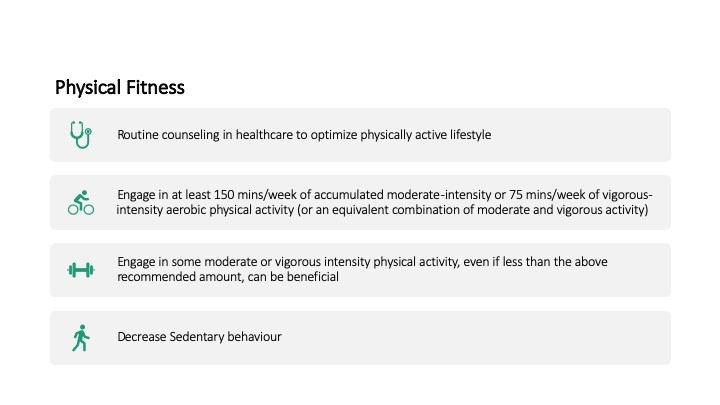

“Cardiovascular health after 10 years: What have we learned and what is the future” was my topic of choice from this year’s AHA21 main scientific sessions. It has been over 10 years since American heart Association (AHA) published a formal definition of cardiovascular health (CVH). In the last 10 years, more than 2,000 publications have tried to address the concept of CVH. AHA 2020 impact goal was to improve the CVH of ALL Americans by 20%, while reducing deaths from cardiovascular (CV) disease and stroke by 20%. Seven key health metrics were used to define CVH including: smoking status, physical activity, healthy diet, blood glucose level, blood cholesterol level, and blood pressure. Each metric was stratified into three statuses: poor, intermediate, and ideal. The initial approach was to improve individuals’ health from poor status into intermediate status and subsequently to ideal status and later promote and preserve ideal CVH through individual’s life(1).

In the last 10 years, many community-based cohort studies including Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC), Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA), and Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) have investigated the association of CVH metric with CV outcomes. A meta-analysis of 13 studies showed that as the number of Ideal CVH metrics decrease the relative risk of all-cause mortality and CV mortality increase in a linear fashion(2). Moreover, studies have expanded the impact of CVH metrics on other chronic disease like cancer, chronic kidney disease, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip fracture(3).

Disappointingly, national data have shown that high CVH is uncommon. Only 7% of U.S. adult population meets the criteria for high CVH, 34% for moderate CHV and 59% for Low CVH group(4). It is estimated that 70% of CV events are attributable to low/moderate CVH and up to 2 million CV events can be prevented if all U.S. adults attained high CVH(5). This implies that potential impact of maintaining high CVH is substantial. The question is how early we should intervene to maintain high CVH.

Prevalence of ideal CVH decline significantly with age. In a study of pooled data from 5 community-based cohort, CVH trajectories were defined starting from age 8 to age 55. 5 unique trajectories have been identified. The prevalence was 30.7% for high rapid decline, 10.3% for intermediate rapid decline, 24.3% for high slow decline, 17.4% for intermediate stable and 17.3% for high stable trajectory(6). These trajectories showed that by age 8, already 20% of 8-year-old children do not have ideal CVH. Loss of ideal CVH metrics occurs at different rate across life span, but late adolescence seems to be a critical time where rapid CVH decline occurs. Moreover, analysis of baseline demographic characteristics by CVH trajectory showed that high stable trajectory is most common among white females and high rapid decline trajectory is most common among African American males. Finally, individuals with high stable trajectory were more likely to have ideal diet and physical activity compared to other CVH metrics at baseline (smoking, blood pressure, glucose, lipid level) suggesting that the best approach to maintain ideal CVH is through promoting healthy behavior.

References:

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Guo L, Zhang S. Association between ideal cardiovascular health metrics and risk of cardiovascular events or mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(12):1339-46.

- Ogunmoroti O, Allen NB, Cushman M, Michos ED, Rundek T, Rana JS, et al. Association Between Life’s Simple 7 and Noncardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(10).

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254-e743.

- Bundy JD, Zhu Z, Ning H, Zhong VW, Paluch AE, Wilkins JT, et al. Estimated Impact of Achieving Optimal Cardiovascular Health Among US Adults on Cardiovascular Disease Events. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(7):e019681.

- Allen NB, Krefman AE, Labarthe D, Greenland P, Juonala M, Kahonen M, et al. Cardiovascular Health Trajectories From Childhood Through Middle Age and Their Association With Subclinical Atherosclerosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(5):557-66.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

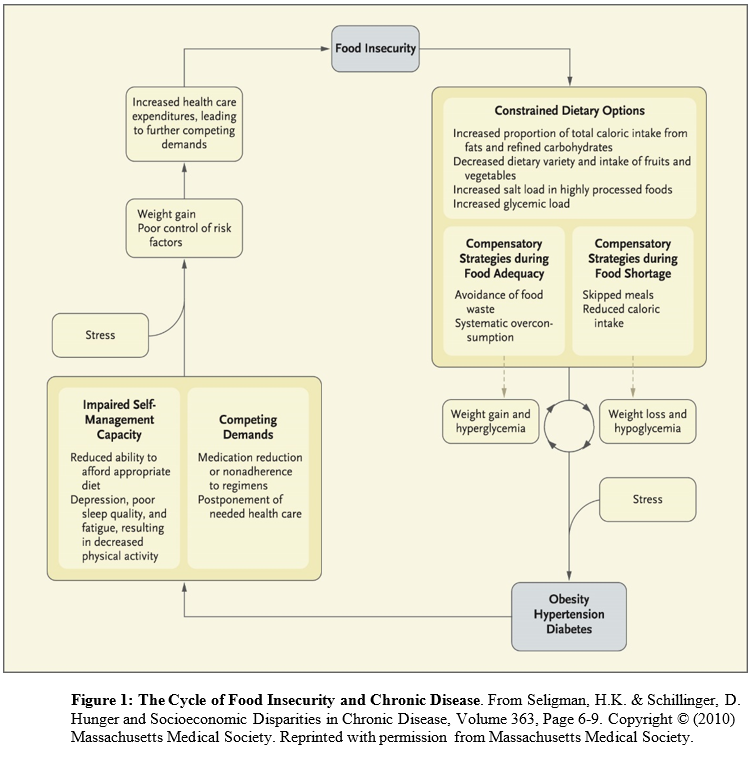

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes. And to be truly inspired, please add the

And to be truly inspired, please add the

![Caption: A key Healthy People 2020 goal is to “create social and physical environments that promote good health for all”. You can learn more [here]. Image Source: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health](https://earlycareervoice.professional.heart.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2019/03/SDOH_fromHealthyPeople2020.png)