In defense of peer review

The generation of knowledge, through rigorous, established systematic methods has informed much of our progress in the past few centuries. Science guides all aspects of healthcare today including how we develop the new medications, therapeutic procedures, and non-pharmacological interventions that have improved the quality and duration of human life. Many of the crucial gates in the scientific journey- funding, ethical approval, and dissemination- are guarded by the process of peer review; a process that is increasing under attack in our current hyper-reactive, digital, media cycle.

Peer review is the critical appraisal of a scientific work by those who have requisite knowledge to evaluate one or more aspects of the work. It is a panel of experts in the related field who understand the importance and novelty of the questions under consideration and the rigor and trustworthiness of the methods proposed or employed to answer that question.

Peer review takes time. Time to find agreeable reviewers with the right expertise, time to review and think about the science, and time to determine how to weigh those critiques against the community’s need for information. From the early days of the novel coronavirus pandemic, this balance of time needed for peer review and unquenchable public thirst for rigorous information has been dominating the conversations at leading medical and scientific journals around the world. To better understand how these decisions are made and what we as clinicians, scientists, and health care consumers need to consider when reading and sharing emerging science, I spoke with Dr. Joseph Hill, the Editor in Chief of Circulation one of 12 AHA Journals.

Even though peer review is an established practice, it is important to start by questioning why we should even do it. Unquestionably, the value of thoughtful peer review is that it enhances the quality of the science. “We [the AHA journals)\] handle approximately 20,000 manuscripts a year and with extraordinarily rare exceptions, the paper always gets better with peer review”.

Having now published many of my own scientific manuscripts, I know the pain of peer review well. “They” missed that detail on line 176. “They” clearly lack the expertise to evaluate my work. “They” kept this manuscript for 8 months before sending their disposition! However, I also know that some of the best revisions to my papers have come from generous peer reviewers. Reviewers who volunteered to spend their time reading my papers and think deeply about my findings in the context of larger literature. While painful, the constant assessment and evaluation of our science is critical to improving the quality and impact of our work.

Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, up to 10 experts, including peer reviewers, statisticians, and editors, would review a manuscript for Circulation. But the need for up-to-date information about the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of COVID-19 challenged Circulation’s editorial team to move fast. While recognizing that it’s “hard to do good science in a war zone”, the quality of published science cannot be compromised in times of crisis. Dr. Hill continues, “We are walking a fine line between trying to get the information out as quickly as possible but we recognize that [in clinical science] we could make it worse and could do harm. So we have to maintain our high standards but function at a high velocity.”

High velocity seems an understatement. After an initial call for high-quality COVID-19 related papers, the editorial team has done over 300 fast track reviews, contributed to a curated coronavirus and cardiovascular disease collection, and conducted 17 interviews with experts working on the front line around the world. All in the past month. This work is exhausting but done with great energy by a team inspired to advance “cardiovascular science for the good of humanity, especially during these times of urgent challenge, anxiety, and forthright resolve.”

Peer review is the best process we have for evaluating science; but peer review is done by peers- busy, human, distractible peers- who will make mistakes. This is why many reputable journals require an editorial screen and at least two peer reviews before it can make a decision on a manuscript. Scientific volunteers do this work. Which brings us to what you, as an early career professional can do. Peer review relies on us—all of us—to sign up to review, accept the invitation to review, and spend the time carefully doing the review. You may wonder if you have the expertise to peer review for Circulation or another AHA Journal; you likely do and you should. Dr. Hill remarked that “some of the best reviews I’ve seen are from early-career scientists”. If you are interested in helping to contribute to peer review and the sharing of good cardiovascular science, considering signing up to be a journal reviewer in your AHA Science Volunteer Form or emailing Dr. Hill your interest in reviewing for Circulation.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

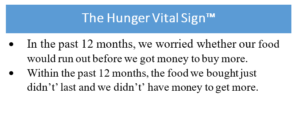

I know, we have to fit so much into each patient encounter that trying to fit in one more thing seems impossible. But a quick, simple strategy is to administer the

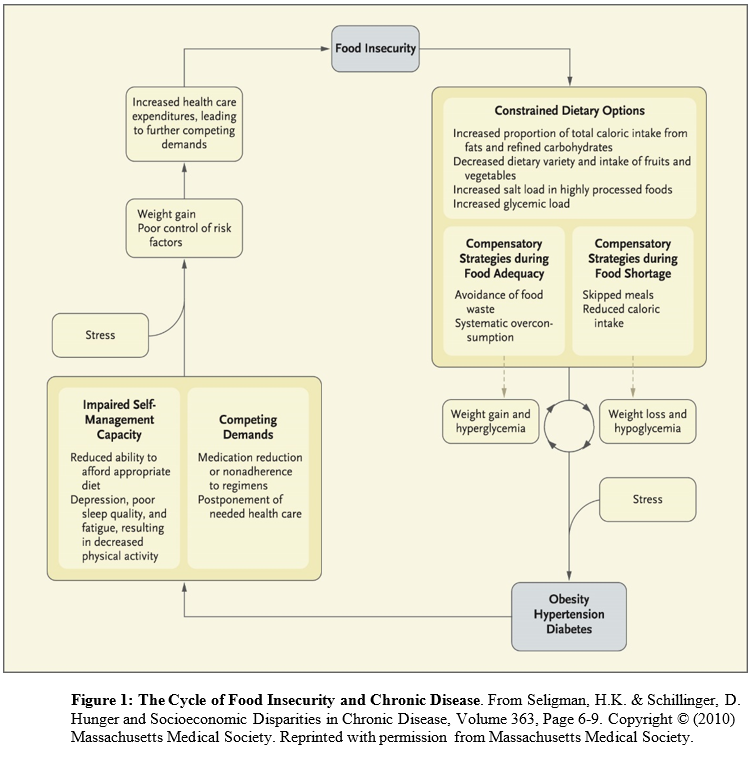

I know, we have to fit so much into each patient encounter that trying to fit in one more thing seems impossible. But a quick, simple strategy is to administer the  Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

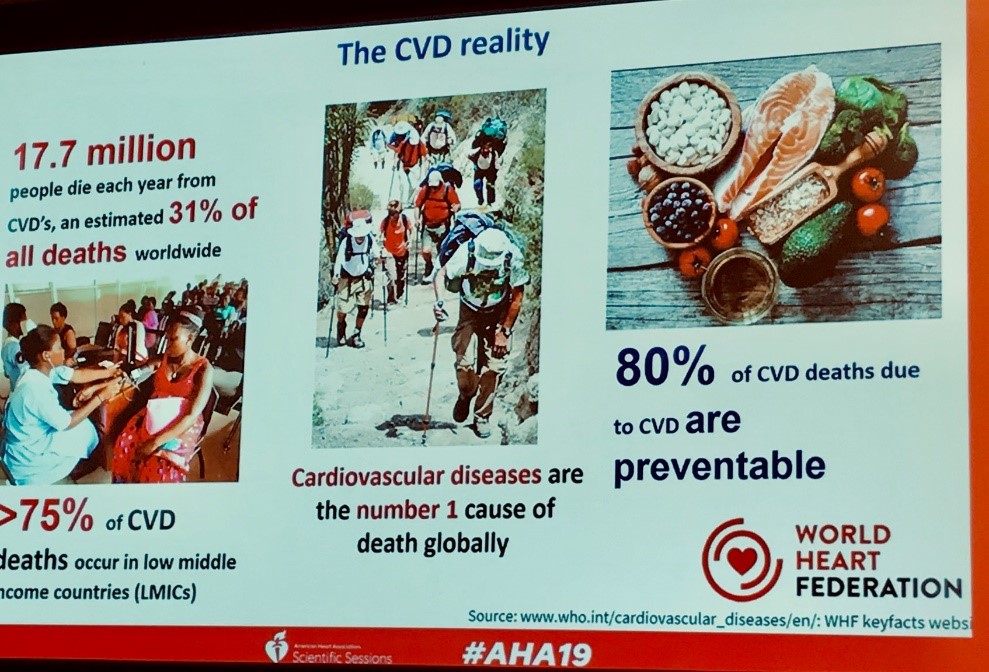

Yet, we may not always recognize that those at risk for cardiovascular disease in other parts of the world have challenges that don’t allow for equitable access to the benefits of this knowledge. Which is why I was delighted to see so many sessions on global cardiovascular disease at #AHA19. To kick off this programming, the World Heart Federation and the American Heart Association hosted a panel of Dr. Thomas Gaziano of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Rita Kalyani of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Dr. Dorairaj Prabhakaran of the World Heart Federation. Together, they described the rapidly growing burden of cardiovascular disease; potential technological innovations for controlling cardiovascular risk factors in low and middle income countries; the increasing prevalence of shared risk factors with, and consequences of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases; and health system interventions to reduce cardiovascular morbidity. While this session highlighted challenges many low- and middle-income countries face in improving cardiovascular health including shortages of a trained healthcare workforce, inconsistent access to safe essential medicines, and more. It also provoked optimism because solutions are within our reach. Dr. Gaziano said that these strategies are “More about changing the mindset [of healthcare systems] to embrace chronic disease management rather than acute care or emergency needs only”.

Yet, we may not always recognize that those at risk for cardiovascular disease in other parts of the world have challenges that don’t allow for equitable access to the benefits of this knowledge. Which is why I was delighted to see so many sessions on global cardiovascular disease at #AHA19. To kick off this programming, the World Heart Federation and the American Heart Association hosted a panel of Dr. Thomas Gaziano of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Rita Kalyani of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Dr. Dorairaj Prabhakaran of the World Heart Federation. Together, they described the rapidly growing burden of cardiovascular disease; potential technological innovations for controlling cardiovascular risk factors in low and middle income countries; the increasing prevalence of shared risk factors with, and consequences of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases; and health system interventions to reduce cardiovascular morbidity. While this session highlighted challenges many low- and middle-income countries face in improving cardiovascular health including shortages of a trained healthcare workforce, inconsistent access to safe essential medicines, and more. It also provoked optimism because solutions are within our reach. Dr. Gaziano said that these strategies are “More about changing the mindset [of healthcare systems] to embrace chronic disease management rather than acute care or emergency needs only”. And to be truly inspired, please add the

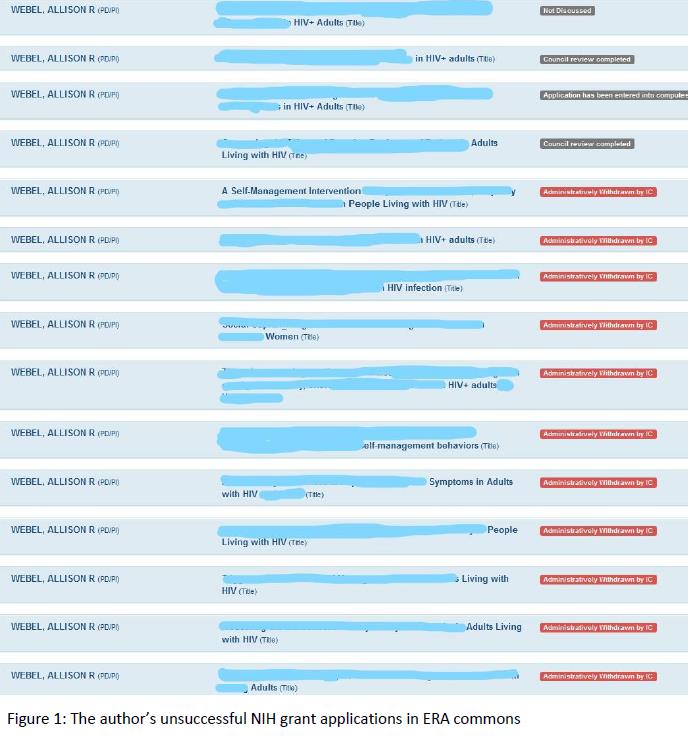

And to be truly inspired, please add the  Throughout my training, I was struck by how similar distance running is to a career in science and to grant writing in particular. When I finished my PhD 10 years ago, I was confident in my ability to write manuscripts and proposals, secure funding, and ultimately do and disseminate the science that would leave a lasting impact on the health of vulnerable populations. This confidence continued even when, during the last few years of my K award, I submitted grant after grant to the NIH only to have them be not discussed repeatedly. I understood that NIH success rates were low, with institutes reporting a range of success rates from ~

Throughout my training, I was struck by how similar distance running is to a career in science and to grant writing in particular. When I finished my PhD 10 years ago, I was confident in my ability to write manuscripts and proposals, secure funding, and ultimately do and disseminate the science that would leave a lasting impact on the health of vulnerable populations. This confidence continued even when, during the last few years of my K award, I submitted grant after grant to the NIH only to have them be not discussed repeatedly. I understood that NIH success rates were low, with institutes reporting a range of success rates from ~