Seeing and Serving Invisible Populations

Like many of you, I chose to be a nurse because I wanted to serve people during their most vulnerable times, knowing that this work would make a difference. Working with people at their most vulnerable has taught me a lot, including that my patients can be braver, kinder, more frightened, angrier, disappointed, lovelier, and in general more surprising than I expect when I walk in the door.

A growing and perhaps surprising population at disproportionally high risk for heart attacks are individuals who identify as transgender. Transgender individuals are those whose gender identity is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. People identifying as transgender can be any age or race, from any background, and reside in all 50 states. In 2016 there were approximately 1.4 million people in the United States who identified as transgender. Given the increase in the transgender population, new initiatives are attempting to understand the unique health needs of this population in order to provide high-quality health care. Little is known about the cardiovascular health of this population, which prompted a recent study by Dr. Alzahrani from George Washington University who found that the transgender population had a higher reported history of heart attacks compared with the cisgender (those whose gender corresponds with their birth sex) population.

This first-of-its-kind study examined approximately 720,000 U.S. adults who completed the telephone-based Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between the years of 2014-2017. Of these, 3,055 adults identified as transgender. In gender stratified analyses, Dr. Alzahrani and colleagues found that after adjusting for known cardiovascular risk factors transgender men had (i.e. they were told by a doctor, nurse or health care professional that they had a heart attack) compared to cisgender men and women. And transgender women had a 2-fold increase in the rate of heart attacks compared with cisgender women. Importantly, the investigators also found that transgender men and women were more likely to smoke and be sedentary, and that these and other traditional risk factors were associated with increased odds of experiencing a heart attack. This suggests that while there are about the long-term cardiovascular risk of gender affirming-hormones, mitigating these traditional risk factors are important first line targets for this and all populations.

In an accompanying editorial Dr. Paul Chan evoked Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, citing the narrator “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” Dr. Chan states that today transgender individuals are invisible. But they don’t have to be. We have to actively reject any implicit or explicit expectations we have about this population and simply see them and treat them as they present. This sentiment is echoed by Dr. Billy Carceres, Nurse and Post-Doctoral Fellow at Columbia University Program for Study of LGBT health, “There’s this perception that we can spot transgender people; but if we don’t ask the question about gender identity we might be missing out on people who are at risk. Patients want to have conversations with health care providers about things that influence their health.”

Table 1 lists several steps that can help us start to have these conversations. Adopting such steps in our clinical practice and research are critical against the backdrop of the increased social stress, poor socioeconomic status, health disparities, violence, and a perpetuating fear of mistreatment by healthcare professionals experienced by transgender populations. These steps will help us to see this invisible population, gain their trust, and ultimately help engage them in activities to improve their cardiovascular health.

|

Table 1. Steps to Reducing Cardiovascular Risk in Transgender Populations |

|

While Dr. Alzahrani’s new article highlights a significant disparity in an often overlooked and vulnerable population, ultimately we need a lot more data before we can develop and tailor cardiovascular treatment guidelines for transgender populations. As Dr. Sangyoon Shin, Medical Director of Co-Management Service for Gender Affirmation Surgery of Mount Sinai stated, “Its important to realize that the transgender population has specialized needs because they are more marginalized and face high rates of discrimination; But the health care practices the guidelines geared towards them need to be just as evidence-based as with any other population.“ Anything less would be a disservice.

People who seek out a health care provider – a nurse, physician, physical therapist, or pharmacist – do so because they need our help. Our job is to serve them, all of them, as they are, with high quality evidence-based health care. How we treat invisible populations, no matter how different or perplexing they are to us, is the true mark of our professionalism.

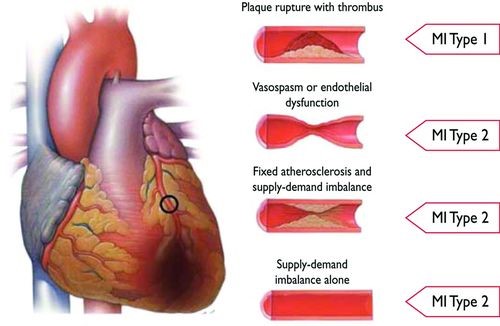

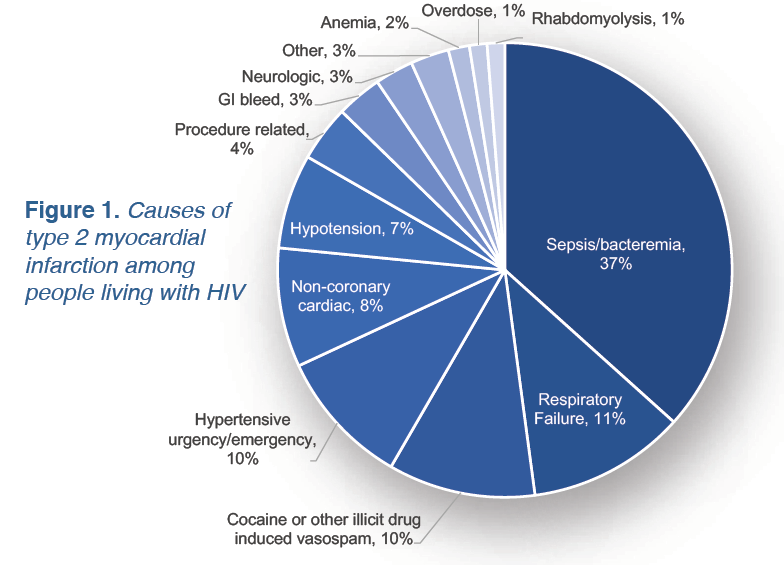

They identified over 1,000 Type 1 and 2 heart attacks and found that age was a primary predictor of the incidence and type of heart attack. Younger people with HIV had 10-fold more Type 2 than Type 1 heart attacks (although rates were low – only 22 heart attacks in this age group). Starting in their 50’s, people living with HIV experienced significantly more Type 1 heart attacks than Type 2. Most interestingly were the heterogeneous causes of the Type 2 heart attacks including sepsis, respiratory failure, pneumonia, hypertensive emergency, and GI bleeds (Figure 1).

They identified over 1,000 Type 1 and 2 heart attacks and found that age was a primary predictor of the incidence and type of heart attack. Younger people with HIV had 10-fold more Type 2 than Type 1 heart attacks (although rates were low – only 22 heart attacks in this age group). Starting in their 50’s, people living with HIV experienced significantly more Type 1 heart attacks than Type 2. Most interestingly were the heterogeneous causes of the Type 2 heart attacks including sepsis, respiratory failure, pneumonia, hypertensive emergency, and GI bleeds (Figure 1).

Dr. Pearson’s own mentors reflected his insatiable curiosity. As a student, he drew from a broad mentoring team that left lifelong impressions of the qualities of good mentor. While excellent teaching was important, more so was the “utterly frank” assessment and advice they provided him. He states, “from them I learned that the primary role of a mentor is to provide an honest, encouraging perspective on the mentee’s ideas, plans and experiences. While some mentors may be tempted to acquiesce or tell mentees what they want to hear- that is abrogation of their responsibility of a mentor.” Such frankness can be tough in today’s academic environment, so to help cultivate this skill, Dr. Pearson’s University of Florida developed the

Dr. Pearson’s own mentors reflected his insatiable curiosity. As a student, he drew from a broad mentoring team that left lifelong impressions of the qualities of good mentor. While excellent teaching was important, more so was the “utterly frank” assessment and advice they provided him. He states, “from them I learned that the primary role of a mentor is to provide an honest, encouraging perspective on the mentee’s ideas, plans and experiences. While some mentors may be tempted to acquiesce or tell mentees what they want to hear- that is abrogation of their responsibility of a mentor.” Such frankness can be tough in today’s academic environment, so to help cultivate this skill, Dr. Pearson’s University of Florida developed the  Whether or not scientists should blog has been hotly debated. In 2018, Eryn Brown and Chris Woolston published a

Whether or not scientists should blog has been hotly debated. In 2018, Eryn Brown and Chris Woolston published a

However, industry and foundation grants are not without their downsides. The panel agreed with Majken Jensen, PhD of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who said these grants are often smaller than federal grants, tend to favor academic celebrities, have low/no indirect rates and can be more heavily taxed by academic institutions, and (in the case of industry funding) can open us up to potential conflicts of interest. But science is a business and early career scientists need money to do their work, so with the limitations acknowledged the panel started to share strategies for obtaining foundation and industry funding.

However, industry and foundation grants are not without their downsides. The panel agreed with Majken Jensen, PhD of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who said these grants are often smaller than federal grants, tend to favor academic celebrities, have low/no indirect rates and can be more heavily taxed by academic institutions, and (in the case of industry funding) can open us up to potential conflicts of interest. But science is a business and early career scientists need money to do their work, so with the limitations acknowledged the panel started to share strategies for obtaining foundation and industry funding.