The Rising Value of Plain Science Talk: Part 2

In part 1 of this blog series, I laid out two main plot points that I wanted to focus on when it comes to the ideas behind Plain Science Talk, 1) Traditionally scientific information has been communicated in extremely technical and specialized formats, geared towards peers and subject matter experts, and 2) Traditional spaces where science information is shared tend to be “closed circuits” of pay-walled and sometimes hard to discover specialty journals, coupled with once or twice a year professional gatherings like conferences and workshops. While these structures were never intended as barriers, their historical origins and continuation to our present-day do contribute to the overall limitation of science information dissemination, and the ability to maximize the benefits of science in the broadest forms possible.

In an effort to spotlight novel approaches that can be leveraged to expand outreach, and provide a path to more science being available to the global population, I pointed out Knowledge Transfer and Translation (KTT) and Online-based Media, as key strategies and tools that can help achieve our desired aims. The ultimate goal here is to show, with a few examples, how science can be adapted and modernized in a way that effectively contributes, not just to other scientists, but to a much wider proportion of the public.

(Submitted by author, CC-0 images at pixabay.com)

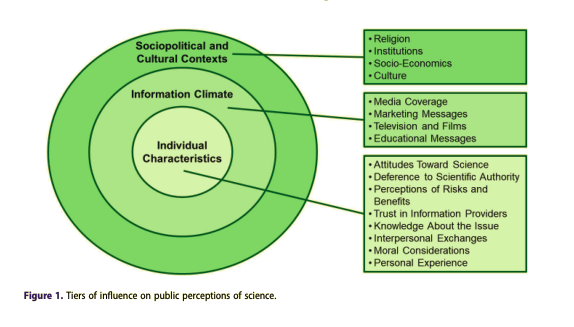

If the past year (and still counting) of the pandemic has exposed us to one thing, well that would be the under-prepared healthcare states that our various global societies are existing in, with regards to delivering and optimizing public health. The other thing that the Covid-19 pandemic has shown us is the need for amplified and optimized science communication approaches so that the general public can be better served by the information scientists have to offer. Better communication will also help to clarify the reasons and factors involved in how science operates, and how the information gathering and disseminating process is always in a state of evolution and advancement.

The spotlight I want to place on KTT is geared towards emphasizing the difference between information sharing between specialists versus information sharing with non-specialists and multidisciplinary audiences. The traditional framework of scientific journals and specialty conferences is based on a “membership” structure: paid subscriptions to high impact/highly specialized publishing platforms, as well as tiered annual membership fees, to access conferences and participate in ancillary workshops and seminars constructed by other members of the professional organization. There is in fact value in this framework. I believe for the most part it serves the greater good for specialists and highly-invested individuals to have domains where their interactions are concentrated and their in-group information sharing is optimized.

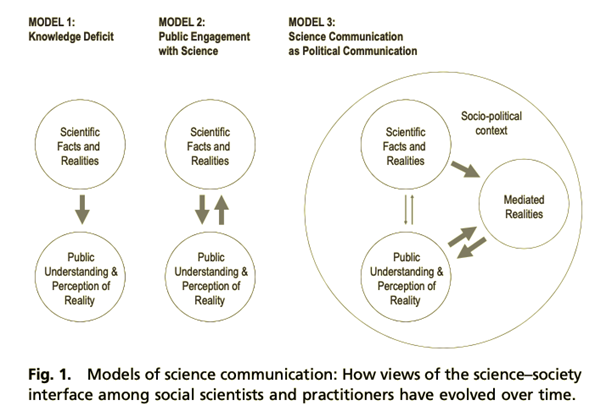

This is undoubtedly the main reason why these types of specialized subject matter communication approaches exist. These methods encourage and facilitate science advancement by having highly knowledgeable experts engage with one another to challenge and expand the potential of information gathering. So my spotlight and encouragement for broader Knowledge Transfer & Translation are not meant to be a replacement to the first-order framework of in-group communication, but instead, it is my attempt to highlight the importance of what I’ll call “second-order communication” framework. This is the communication between subject matter experts and the more generalized audience, composed of multidisciplinary groups and specialists in other fields, as well as casually interested and invested members of society, without specific professional ties to the scientific data being communicated.

The majority of KTT approaches in the scientific fields are left to individuals that act as separate but integral links in the information chain. The original researchers are reliant on others to absorb the information they produce and move it in a direction that can be used by others in organizations such as government policymakers, industrial development, news media sharing, etc. This is mostly because the traditional academic/educational models experienced by scientists are very rarely designed with broader communication as a required skill to develop and expand over time. Science communication is classically seen as published articles in specialized journals, and infrequent conference talks & presentations to rooms full of experts in the fields related to the topics discussed.

Transfer of knowledge to a much wider group of people is often thought of as a task left for other individuals (not the original scientists) to deliver. The idea of Knowledge Translation is even more distant as an aim from many scientists. Translation (taking the gained information and finding a way to make it more immediately impactful in society, either by the production of something new or implementing new policy) is the most underserved aspect of science information gathering. Thousands of new research articles are produced every year, the vast majority of it goes unnoticed and without impacting people or the planet we share with millions of other species.

(Submitted by author, CC-0 images at pixabay.com)

My second spotlight is aimed directly at where you and I are in right now, namely “the internet”! Many have long seen the potential that online-based communication has to offer when it comes to expanding the reach of specialists. I won’t go through a timeline of the evolving state of the web, but suffice to say, in the most recent versions of online media, the expansion of reach that individuals have, especially through the use of Social Media (#SoMe), has reached a level that greatly facilitates information sharing and that idea of “second-order communication” between specialists and a wider group of individuals unrelated to the field specialists within an in-group.

The expanding communication platforms available for scientists and other subject matter experts must be seen for their highly valuable potential. The ability to directly share information with the public in forms that are not “pay-walled” or exclusive to specialists is undeniably a positive evolution of the whole communication framework. Having said that, it is important to note that new forms of communication also bring about the important need to learn and gain incremental experience in the methods and approaches that optimize the final goal of beneficial information sharing with wider audiences.

Everyone needs “practice” to get better at information sharing (it certainly takes “practice” to get better at information gathering). It doesn’t help that classically, science communication has been left out of the traditional structures of science education and implementation. But now is as good a time as any to commit to gaining new skills (one of the side effects of the pandemic on society as a whole, is realizing the need for novel skill acquisition!). The online world is rapidly evolving as well, and with it, new communication frameworks are quickly becoming more normalized (web-based video conferencing, more robust social media use, new platforms, and functionalities on existing apps, etc.). The more experts are able to directly communicate with each other and with broader groups of people, the faster we can reach the aims of KTT and provide our communities with useful data that can benefit us, and the world we live in.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

And to be truly inspired, please add the

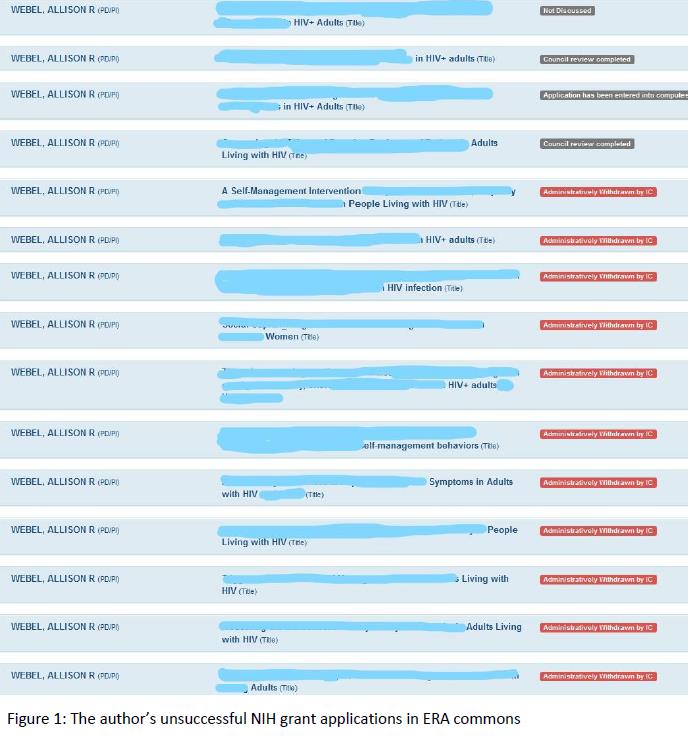

And to be truly inspired, please add the  Throughout my training, I was struck by how similar distance running is to a career in science and to grant writing in particular. When I finished my PhD 10 years ago, I was confident in my ability to write manuscripts and proposals, secure funding, and ultimately do and disseminate the science that would leave a lasting impact on the health of vulnerable populations. This confidence continued even when, during the last few years of my K award, I submitted grant after grant to the NIH only to have them be not discussed repeatedly. I understood that NIH success rates were low, with institutes reporting a range of success rates from ~

Throughout my training, I was struck by how similar distance running is to a career in science and to grant writing in particular. When I finished my PhD 10 years ago, I was confident in my ability to write manuscripts and proposals, secure funding, and ultimately do and disseminate the science that would leave a lasting impact on the health of vulnerable populations. This confidence continued even when, during the last few years of my K award, I submitted grant after grant to the NIH only to have them be not discussed repeatedly. I understood that NIH success rates were low, with institutes reporting a range of success rates from ~