Need for COURAGE to evaluate for ISCHEMIA?

The Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial1 has been a landmark in clinical decision-making for patients with stable ischemic heart disease – leading to a paradigm shift in clinical care by establishing that revascularization/percutaneous coronary intervention(PCI) in patients with stable ischemia did not reduce subsequent mortality or myocardial infarction(MI) outcomes over ‘optimal’ medical therapy. There was a reduction of ischemia-driven revascularization with invasive management-which has been attributed as a ‘soft end-point’. However, there have been criticisms of the trial – one of which has been that patients had not been selected based on a significant extent or severity of ischemia. This has been fueled by a subsequent analysis from the courage trial investigators which revealed mortality/MI outcomes benefit with revascularization in patients with moderate to severe ischemia2. This has led the national institutes of health(NIH) to evaluate the hypothesis of upfront revascularization with the eponymous International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial3-the baseline characteristics of the participants having been published recently. So, there was tremendous excitement and interest for the presentation of the ISCHEMIA trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association (AHA) in Philadelphia in November, 2019-which I was fortunate to be able to attend in person with assistance from the AHA Early Career Blogger program.

The results4 validated the earlier COURAGE trial results with no significant differences overall with invasive vs conservative management strategies with cardiovascular mortality, overall myocardial infarction rates, unstable angina, heart failure, and resuscitated cardiac arrest as well as the composite, primary end-point. The presentation of the primary trial itself referred to the outstanding questions after the COURAGE trial results-namely:

- Do higher risk patients based on substantial ischemia benefit?

- Does elimination of referral bias by randomizing before cardiac catheterization cause outcomes to differ by planned strategy of management?

- Does use of newer stents and FFR as needed impact outcomes?

The mode revascularization appeared to reflect contemporary practices with 98% of patients receiving PCI being treated with drug-eluting stents and 93% of bypass surgery candidates receiving a arterial graft. The trial did show a higher risk of all cause MI (procedural+non-procedural) at 6 months with invasive management which was reversed to a significant extent by 4 years of follow-up. Additionally, patient with significant angina at baseline had improvement of their quality of life and angina symptoms with revascularization. The above findings with MI were in contradiction to the COURAGE results-which however did show improvement in angina symptoms with revascularization.

These findings made me wonder if the ISCHEMIA trial had significant differences amongst the participants compared to the COURAGE trial-other than those mandated by trial protocol? I reviewed the baseline characteristics of the participants from the index publication of the COURAGE trial for both the PCI and the OMT groups. These were then compared and contrasted against the baseline characteristics identified for the ISCHEMIA trial population3.

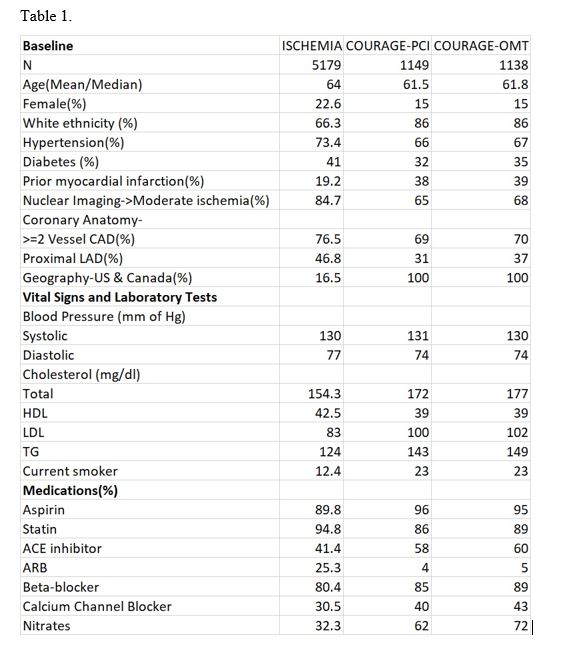

The baseline characteristics of the ISCHEMIA trial population appeared to mirror the baseline characteristics in the two arms of the COURAGE trial published over a decade ago with some notable differences – Table 1. ISCHEMIA enrolled more than double the number of participants of the COURAGE trial, and consequently has greater statistical power in evaluating clinically meaningful end points. In terms of demographics, ISCHEMIA has enrolled significantly higher numbers of females and those of non-white ethnicity. ISCHEMIA also appears to have enrolled a significantly higher proportion of patients with hypertension and diabetes, but a lower proportion of patients with prior myocardial infarction. There also appears to be a greater number of patients with multi-vessel coronary disease and proximal left anterior descending disease in ISCHEMIA. There is a stark contrast in the location of recruiting sites – COURAGE was entirely US and Canada-based, whereas ISCHEMIA has only enrolled 16.5% of patients in the US and Canada. Participants of the ISCHEMIA trial also appear to have a better lipid profile and lower prevalence of active smoking. In terms of the medical treatment-more patients appear to be on statins in ISCHEMIA while surprisingly the proportion of other guideline-directed medications for treating coronary artery disease like aspirin, ACE inhibitor, beta blockers and antianginals appear to be lower. And eventually, only 41% of the trial participants were considered at ‘high level’ of medical optimization4.

The differences in the baseline characteristics between COURAGE and ISCHEMIA may have important implications. ISCHEMIA appears to have recruited a higher risk population including more women that will evaluate clinical benefits with strategy of upfront revascularization. Less than a fifth of the population being recruited from US Canada raises the question of the applicability of the results to the general US population. It is also of interest that a lower proportion of patients were on guideline directed medical therapy excepting for statins, when contrasted against a population of a similar US-based trial published over a decade ago. In summary, ISCHEMIA has important differences in the population recruited in comparison to the COURAGE trial – and these may need to be taken into account for interpretation of the final results, when published.

References:

- Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR, Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, Booth DC, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini GB, Weintraub WS; COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 12;356(15):1503-16.

- Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, Mancini GB, Hayes SW, Hartigan PM, Weintraub WS, O’Rourke RA, Dada M, Spertus JA, Chaitman BR, Friedman J, Slomka P, Heller GV, Germano G, Gosselin G, Berger P, Kostuk WJ, Schwartz RG, Knudtson M, Veledar E, Bates ER, McCallister B, Teo KK, Boden WE; COURAGE Investigators. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008 Mar 11;117(10):1283-91.

- Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, et al; for the ISCHEMIA Research Group. Baseline characteristics of participants in the IISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial [published February 27, 2019]. JAMA Cardiol. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0014.

- https://www.ischemiatrial.org/system/files/attachments/ISCHEMIA%20MAIN%2011.20.19%20with%20background.pdf . Last accessed 11/28/2019

The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.