It’s been a very hot summer so far. These days many of us are spending time with our families under the sun. Somehow, medicine still creeps into our summer days. Many of us will steal brief moments to check emails, open a link to an article or interact with colleagues on social media under a colorful parasol umbrella with a cold iced juice in our hand.

My last blog was the first of a series describing bifurcation stent strategies. This month the focus is Culotte technique. My intention is to provide a breezy summer reading that’s concise and illustrative, designed especially for those of us still on our summer ventures.

Here is Episode 2: CULOTTE TECHNIQUE

The Culotte technique, also commonly known as Y or Trouser stenting, was initially described by Chevalier et al in 1998.1 At that time, two equal sized bare metal stents were deployed in the main branch (MB) and side branch (SB) with an overlapped segment in the MB before the bifurcation. This was studied in a small population of only 50 patients with true bifurcation lesions. There was a 94% clinical success rate with 3 non-Q wave myocardial infarctions. A 24% late target lesion revascularization rate (TLR) was reported. Although this trial registered excellent short-term results, the technique itself was largely abandoned in the absence of any robust long-term data. With the advent of drug-eluting stents (DES), culotte stenting resurfaced as a viable technique. In principal, this strategy is a trade-off. There is complete coverage of the carina and the ostium of the SB as well as a more uniform drug distribution. However, this is only achieved with a long segment of double layers of metal proximally. The culotte strategy using DES was evaluated in several randomized trials summarized below.

Culotte stenting technique in coronary bifurcation disease: angiographic follow-up using dedicated quantitative coronary angiographic analysis and 12-month clinical outcomes.

A decade after Chevalier, Adriaenssens et al in 2008 published the results of their prospective randomized trial that enrolled patients undergoing culotte stenting with DES (Cypher, Endeavor, polymer-free rapamycin-eluting, Taxus).2 The Medina classification was used to describe the lesions. Angiographic follow-up was performed between 6 and 12 months post-index procedure. Clinical follow-up was 12 months. Culotte technique was used in 134 lesions of which 92.5% were true bifurcations. Angiographic success was achieved in all cases. Restenosis occurred in 22% (0% in the proximal MB, 9.1% in the distal MB, and 16% in the SB). At 12 months, 21% had TLR and stent thrombosis (ST) was 1.5%. Predictors of restenosis were older age, increased bifurcation angle, small SB reference diameter and severe distal main branch stenosis.

Randomized Comparison of Coronary Bifurcation Stenting With the Crush Versus the Culotte Technique Using Sirolimus Eluting Stents

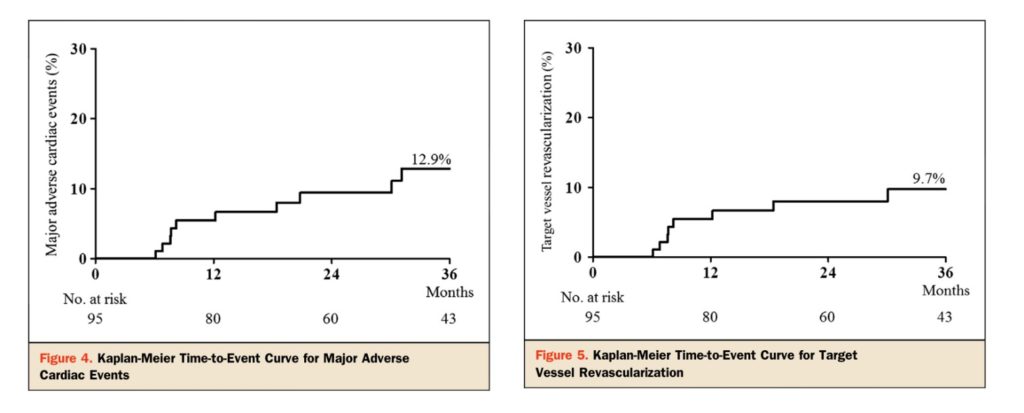

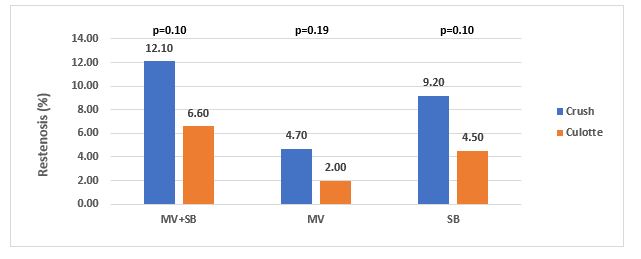

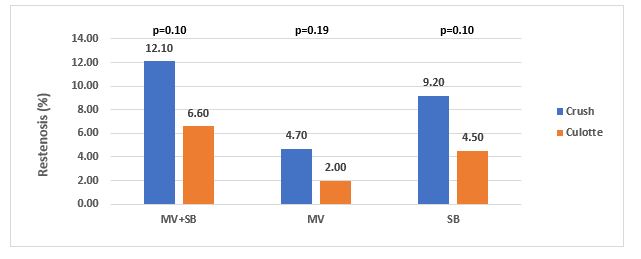

In 2009, Ergilis et al compared two dedicated bifurcation stent strategies, the crush and the culotte, using sirolimus eluting stents.3 A total of 424 patients were randomized (crush [n=209] and culotte [n=215]). The primary end point was major adverse cardiac events (MACE); cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularization (TVR), or ST at 6 months. The results noted that at 6 months there were no significant differences in MACE rates between both groups; crush 4.3%, culotte 3.7% (P=0.87). Procedure and fluoroscopy times and contrast volumes were similar. The rate of myocardial injury defined by elevated biomarkers was 15.5% in crush versus 8.8% in culotte (P=0.08). In-segment restenosis was 12.1% versus 6.6% (P=0.10) and in-stent restenosis (ISR) was 10.5% versus 4.5% (P=0.046) for crush and culotte groups, respectively. The investigators conclude that the angiographic results of both strategies were similar with a trend to less ISR with culotte.

Ergilis et al, Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:27-34

Comparison of Double Kissing Crush Versus Culotte Stenting for Unprotected Distal Left Main Bifurcation Lesions: Results From a Multicenter, Randomized, Prospective DKCRUSH-III Study

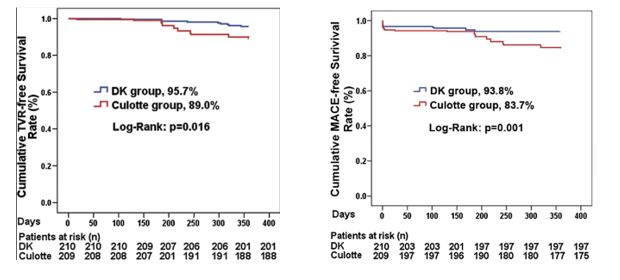

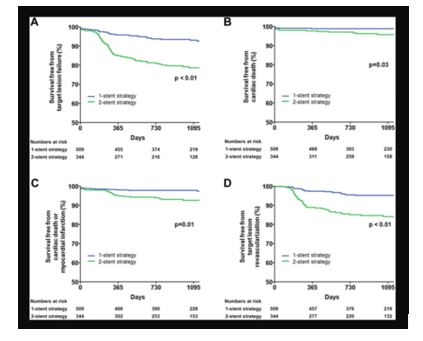

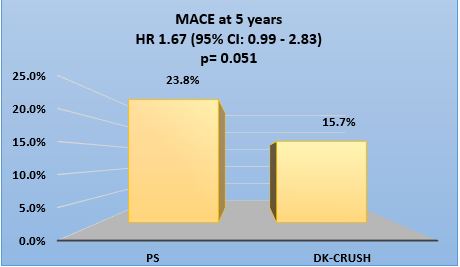

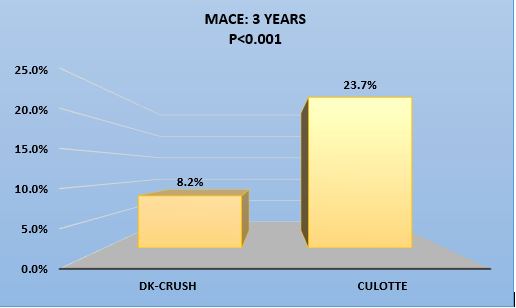

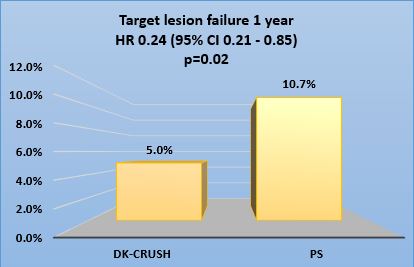

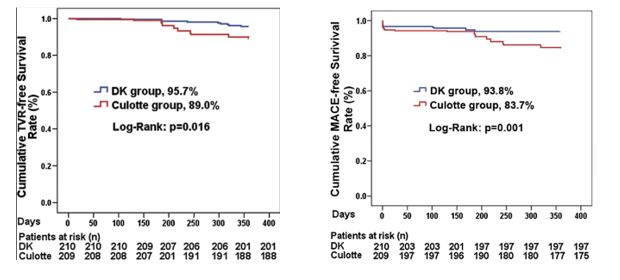

More comparative data was made available in 2013 by Chen et al that employed more contemporary and developed techniques: Double Kiss Crush (DK) and Culotte.4 This study also examined the utility of these techniques in left main lesions. A total of 419 patients with unprotected left main bifurcation lesions were randomly assigned to Double Kiss Crush (210) or Culotte (209) strategies. The primary endpoint was MACE at 1 year, including cardiac death, MI, and target vessel revascularization (TVR). ISR at 8 months was a secondary endpoint. ST was as a safety endpoint. Patients were stratified by SYNTAX (Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) and NERS (New Risk Stratification) scores. In this cohort, the Culotte group had significant higher 1-year MACE rate (16.3%), driven by increased TVR (11.0%), compared with the DK group (6.2% and 4.3%, respectively; all p < 0.05). ISR of the SB was reported to be 12.6% in Culotte and 6.8% in DK (p = 0.037). ST rate was 1.0% in Culotte and 0% in DK (p = 0.248). Furthermore, when stratifying patients with bifurcation angle ≥70°, NERS score ≥20, and SYNTAX Score ≥23, the 1-year MACE rate for DK was 3.8%, 9.2%, and 7.1%, respectively. These rates were higher in Culotte (16.5%, 20.4%, and 18.9%, respectively; all p < 0.05). The investigators concluded that Culotte stenting for unprotected Left Main bifurcation lesions is associated with significantly higher MACE.

Chen et al, J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1482-8

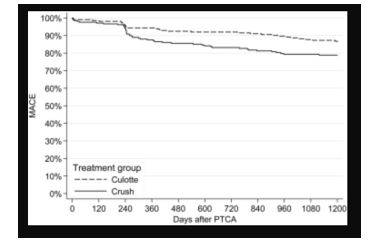

Clinical Outcome After Crush Versus Culotte Stenting of Coronary Artery Bifurcation Lesions: The Nordic Stent Technique Study 36-Month Follow-Up Results

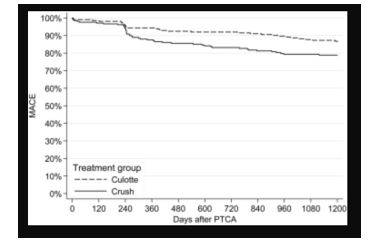

The Nordic trialists also examined the outcomes of this technique in their study.5 The trial provided long term outcome data which is lacking in some of the other published data. A total of 424 patients were randomized to crush or culotte techniques using sirolimus-eluting stents and followed for 36 months. The primary endpoint was MACE (composite of cardiac death, MI, ST or TVR) at 36 months. At 36 months, the primary endpoint rate was 20.6% versus 16.7% (p = 0.32), TLR 11.5% versus 6.5% (p = 0.09), and ST 1.4% versus 4.7% (p = 0.09) in the crush and the culotte groups, respectively. The investigators concluded that outcomes were similar in both strategies.

Kervinen et al, JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:1160-5

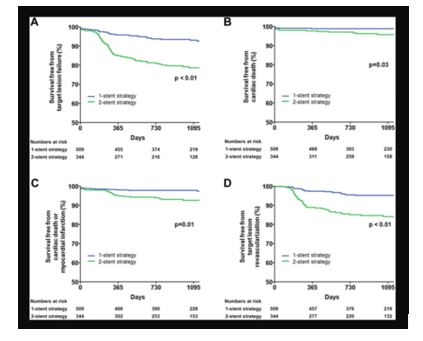

Differential Prognostic Impact of Treatment Strategy Among Patients With Left Main Versus Non–Left Main Bifurcation Lesions Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Results From the COBIS (Coronary Bifurcation Stenting) Registry II

In 2014, Song et al provided outcome data from their retrospective Korean COBIS II registry.6 This registry was unique in that it compared outcomes of left main and non-left main bifurcation lesions using a two stent and single stent strategy. A total of 2,044 patients with non-left main bifurcation lesions and 853 with left main bifurcation lesions were enrolled. The primary outcome was TLF defined as a composite of cardiac death, MI, and TLR. The 2-stent strategy was used more frequently employed in left main disease. At 36 months, the 2-stent strategy was not associated with a higher incidence of cardiac death, MI or target lesion failure (TLF) in the non-left main bifurcation group. However, in those with left main lesions, the 2-stent strategy was associated with a higher incidence of cardiac death, MI and TLF. Investigators, therefore, recommend a single strategy when possible especially for left main lesions.

Song et al, JACC Cardiovasc Interv.2014;7:255-63

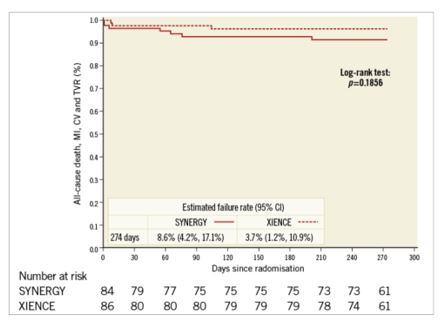

Culotte stenting for coronary bifurcation lesions with 2nd and 3rd generation everolimus-eluting stents: the CELTIC Bifurcation Study

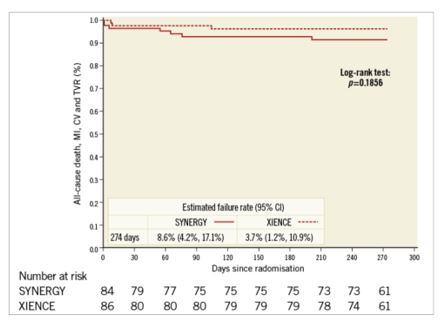

The CELTIC study provides more contemporary outcome data for patients with Medina 1,1,1 lesions treated with a culotte two-stent technique using latest generation Everolimus DES, the 3-connector XIENCE and the 2-connector SYNERGY.7 A total of 170 patients were included. Technical success was noted in >96% of those enrolled. MACE was reported in 5.9% by 9 months. The primary endpoint was a composite of death, MI, CVA, TVF, ST and binary angiographic restenosis. At nine months, the primary endpoint occurred in 19% of XIENCE group and 16% of SYNERGY group (p=0.003). Although this was not a direct comparison of 2-stent strategy to provisional strategy, this trial is more representative of modern day practice with radial access in 96%, latest generation DES and standard proximal optimization techniques.

Walsh et al, EuroIntervention 2018;14:e318-e324

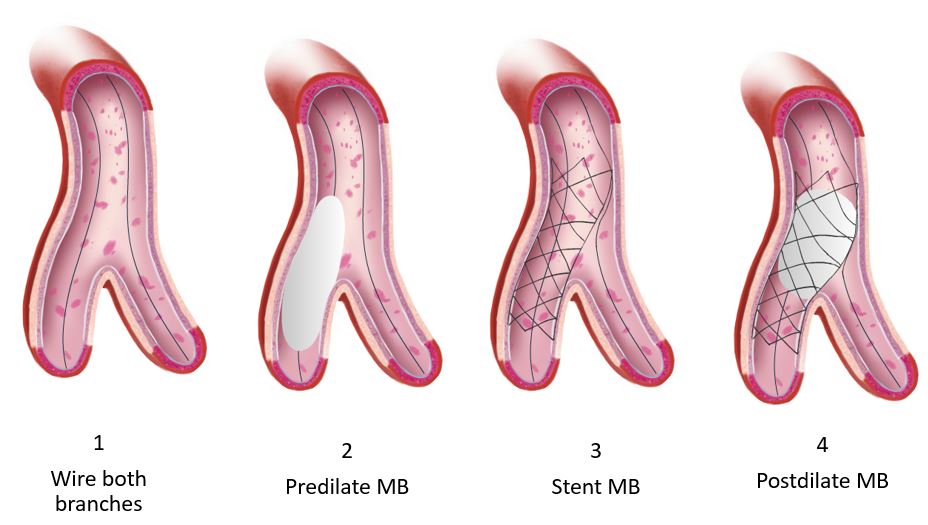

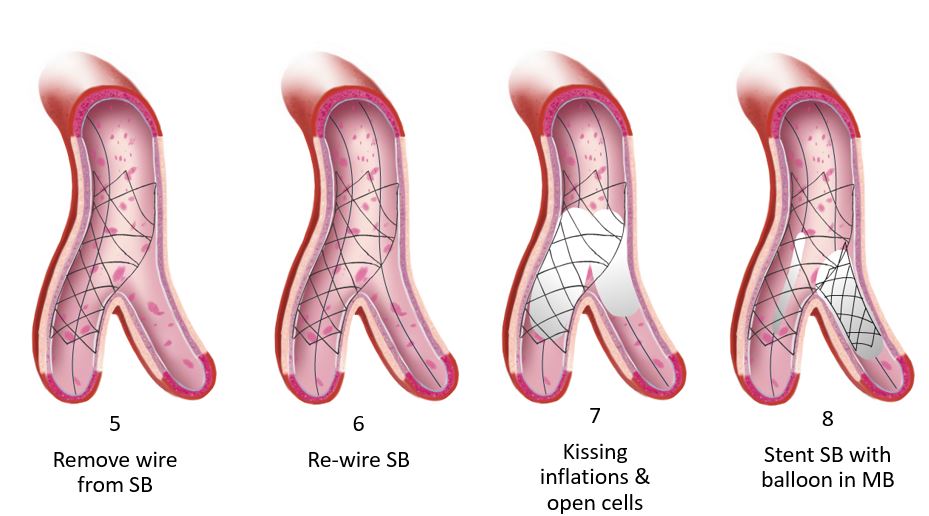

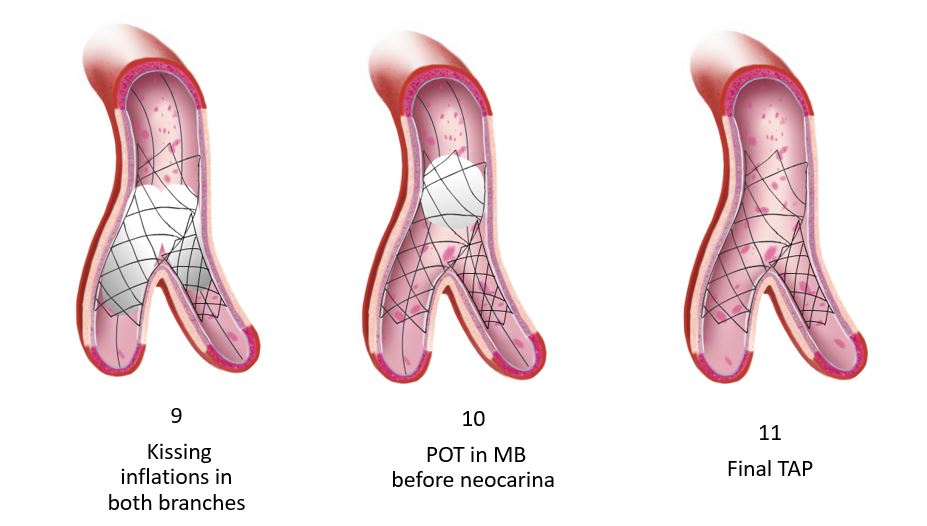

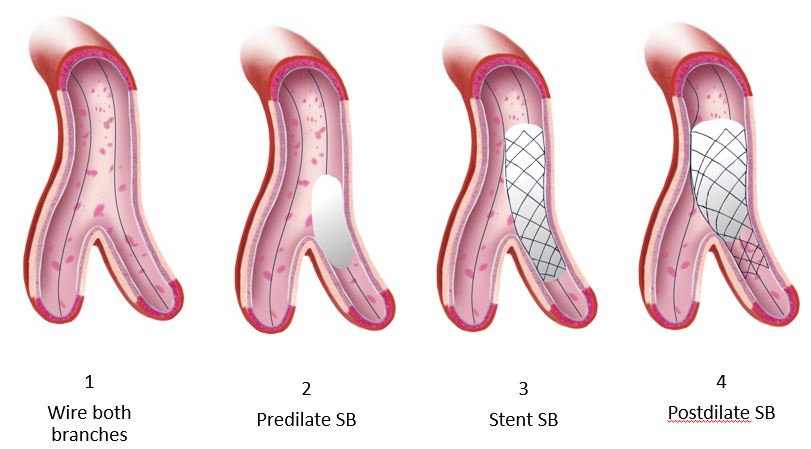

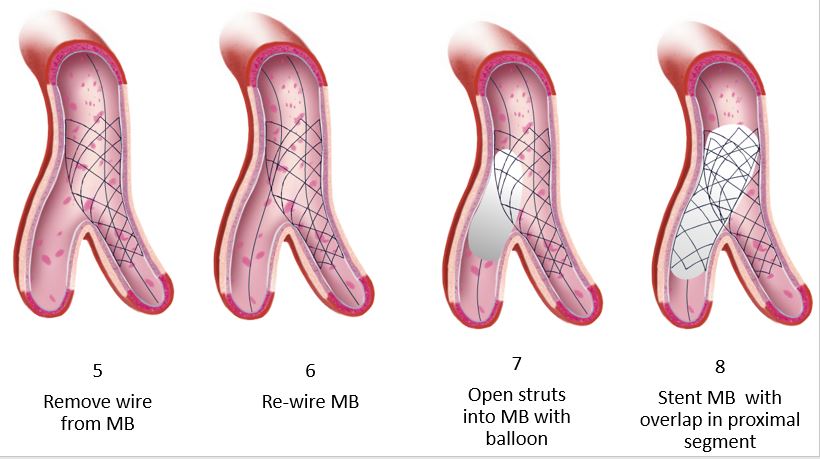

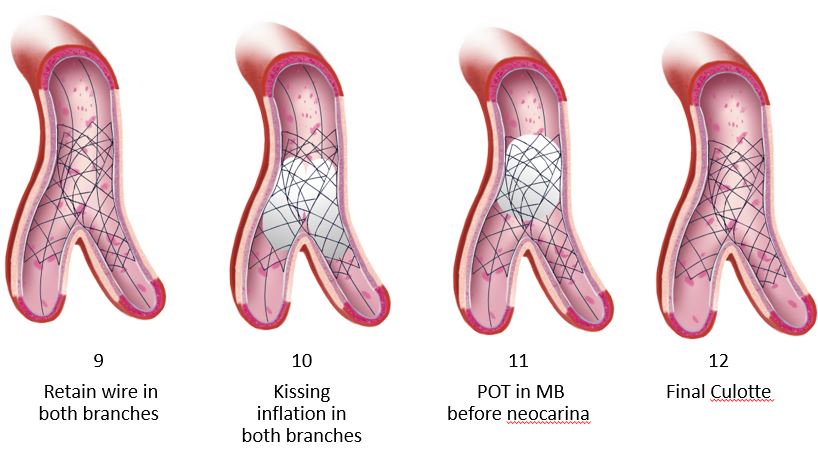

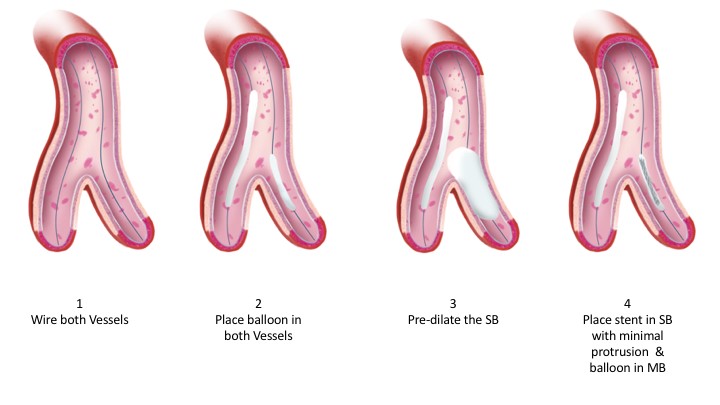

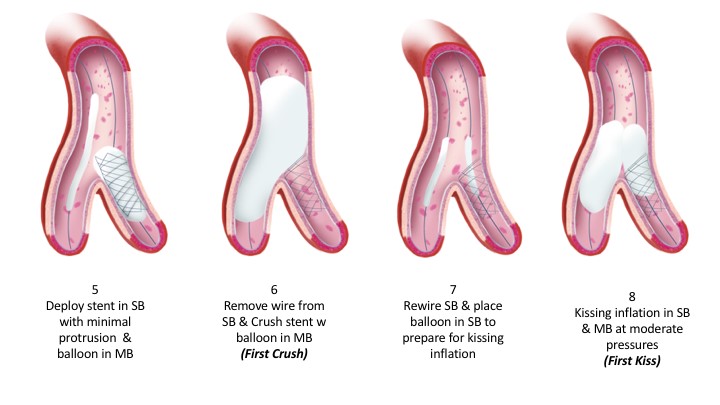

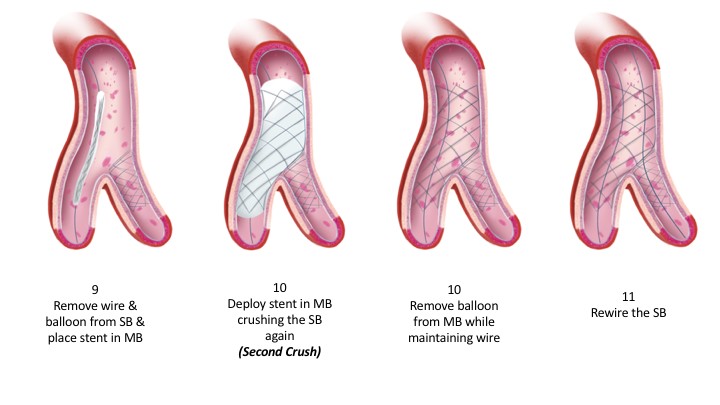

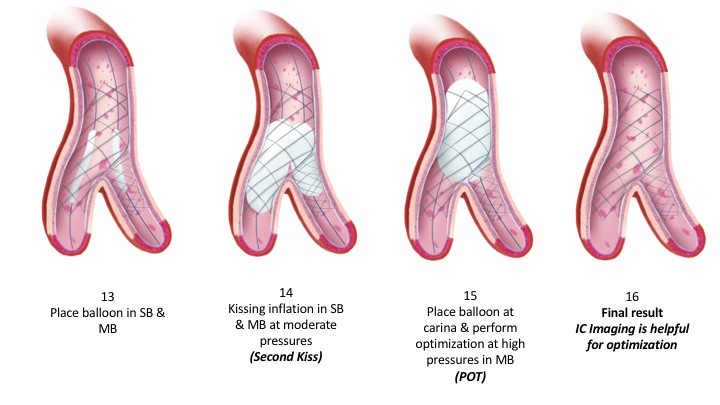

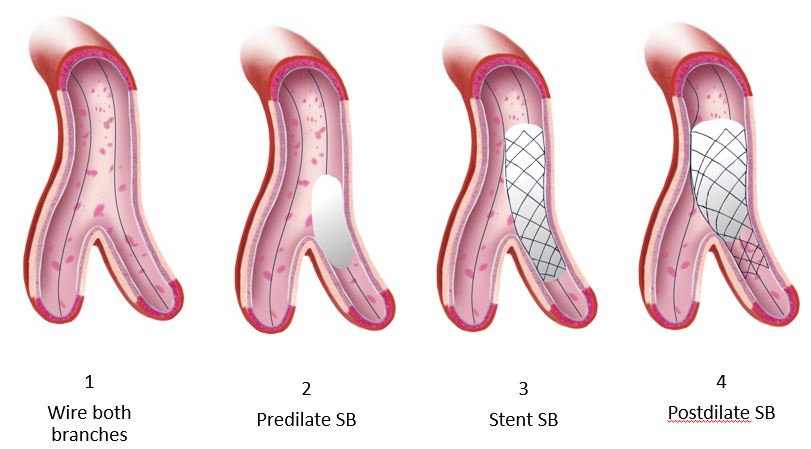

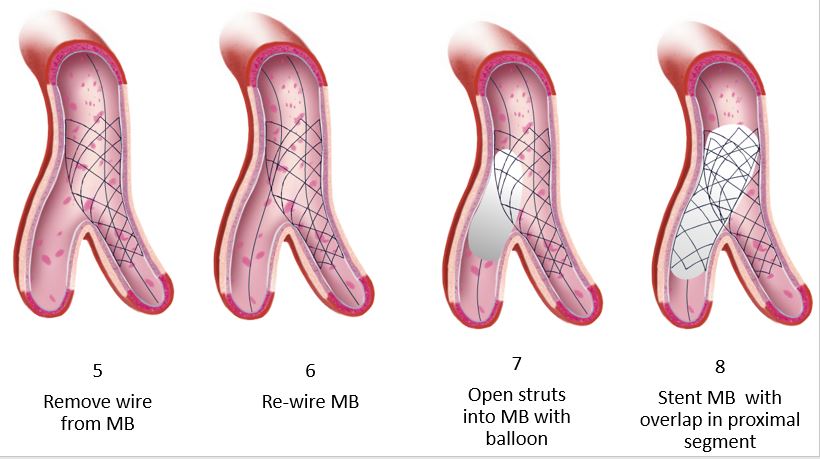

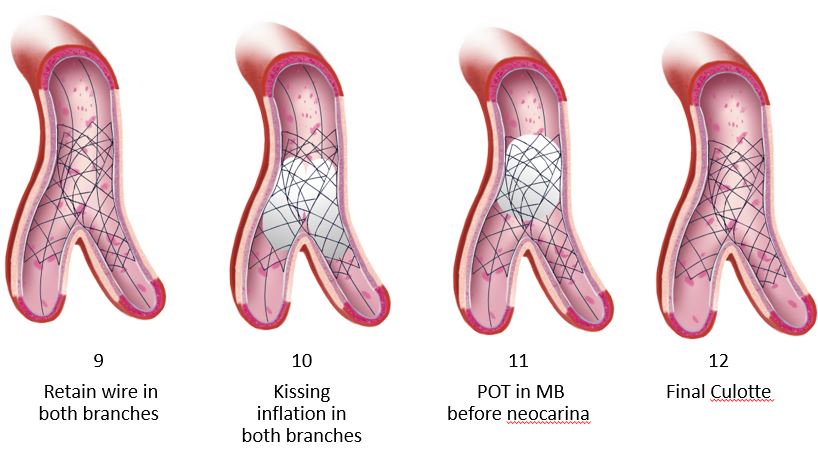

As noted in the trials, the rate of employing this varies considerably, 2% in the COBIS II registry and 66% in Nordic Baltic Bifurcation Study IV. This strategy is most suitable when the SB and MB are similar in size. A mismatch can lead to incomplete SB stent apposition. Additionally, a wide angle between the two branches is an independent predictor of restenosis after culotte stenting. The advantages of this strategy are numerous. It permits one to begin with a provisional strategy that can be converted to 2-stents if necessary. With culotte technique there are only two and not three stent layers in the proximal segment. This facilitates re-wiring into the SB when performing kissing inflations. Culotte ensures complete coverage of all segments especially the ostium with little recoil at the ostium and stent distortion. Below is an illustration of the different steps.

Animations/illustrations courtesy of Graphic Designer Dania Al-Shaibi

Email: [email protected]

References:

- Chevalier B, Glatt B, Royer T, Guyon P. Placement of coronary stents in bifurcation lesions by the “culotte” technique. Am J Cardiol.1998;82:943-9.

- Adriaenssens T, Byrne RA, Dibra A, Iijima R, Mehilli J, Bruskina O, Schömig A, Kastrati A. Culotte stenting technique in coronary bifurcation disease: angiographic follow-up using dedicated quantitative coronary angiographic analysis and 12-month clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J.2008;29:2868-76.

- Erglis A, Kumsars I, Niemelä M, Kervinen K, Maeng M, Lassen JF, Gunnes P, Stavnes S, Jensen JS, Galløe A, Narbute I, Sondore D, Mäkikallio T, Ylitalo K, Christiansen EH, Ravkilde J, Steigen TK, Mannsverk J, Thayssen P, Hansen KN, Syvänne M, Helqvist S, Kjell N, Wiseth R, Aarøe J, Puhakka M, Thuesen L; Nordic PCI Study Group. Randomized comparison of coronary bifurcation stenting with the crush versus the culotte technique using sirolimus eluting stents: the Nordic stent technique study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:27-34.

- Chen SL, Xu B, Han YL, Sheiban I, Zhang JJ, Ye F, Kwan TW, Paiboon C, Zhou YJ, Lv SZ, Dangas GD, Xu YW, Wen SY, Hong L, Zhang RY, Wang HC, Jiang TM, Wang Y, Chen F, Yuan ZY, Li WM, Leon MB. Comparison of double kissing crush versus Culotte stenting for unprotected distal left main bifurcation lesions: results from a multicenter, randomized, prospective DKCRUSH-III study. J Am Coll Cardiol.2013;61:1482-8.

- Kervinen K, Niemelä M, Romppanen H, Erglis A, Kumsars I, Maeng M, Holm NR, Lassen JF, Gunnes P, Stavnes S, Jensen JS, Galløe A, Narbute I, Sondore D, Christiansen EH, Ravkilde J, Steigen TK, Mannsverk J, Thayssen P, Hansen KN, Helqvist S, Vikman S, Wiseth R, Aarøe J, Jokelainen J, Thuesen L; Nordic PCI Study Group. Clinical outcome after crush versus culotte stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic Stent Technique Study 36-month follow-up results. JACC Cardiovasc Interv.2013;6:1160-5.

- Song YB, Hahn JY, Yang JH, Choi SH, Choi JH, Lee SH, Jeong MH, Kim HS, Lee JH, Yu CW, Rha SW, Jang Y, Yoon JH, Tahk SJ, Seung KB, Oh JH, Park JS, Gwon HC. Differential prognostic impact of treatment strategy among patients with left main versus non-left main bifurcation lesions undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the COBIS (Coronary Bifurcation Stenting) Registry II. JACC Cardiovasc Interv.2014;7:255-63.

- Simon J. Walsh, Colm G. Hanratty, Stuart Watkins, Keith G. Oldroyd, Niall T. Mulvihill, Mark Hensey, Alex Chase, Dave Smith, Nick Cruden, James C. Spratt, Darren Mylotte, Tom Johnson, Jonathan Hill, Hafiz M. Hussein, Kris Bogaerts, Marie-Claude Morice, David P. Foley. Culotte stenting for coronary bifurcation lesions with 2nd and 3rd generation everolimus-eluting stents: the CELTIC Bifurcation Study. EuroIntervention 2018;14:e318-e324.