Anxiety, Food Security, & Beyoncé: Addressing Young Women’s Cardiovascular Health

What can you do to address gender disparities in health and health care? In my last post, I suggested working to identify your own bias by increasing your awareness. I’m walking this path, too. A few years ago, I made a concerted effort to diversity my reading habits after I noticed that a huge percentage of the work I was consuming was produced by white men. I spent a year choosing to read only books by women and people of color instead. I learned that it was not hard to do this, but it required that I pay attention. I read a lot of wonderful work that I might have otherwise overlooked, and I was exposed to much more diverse viewpoints. I continue to seek out broad representation, and I suggest a similar approach to reading scientific literature.

Start by paying attention to 1) study populations, and 2) authorship. Are you reading articles about (and by) underrepresented populations? In cardiovascular health, this includes women, who remain underrepresented in clinical trials (estimates as low as 34% of participants in trials supporting drugs for some CV conditions1), clinical practice (just 20% of cardiology fellow are women2), and academia (check out the #nomanels hashtag on Twitter).

Clearly, we need more cardiovascular research by and about women. In this post, I want to highlight some exciting research by and about women.

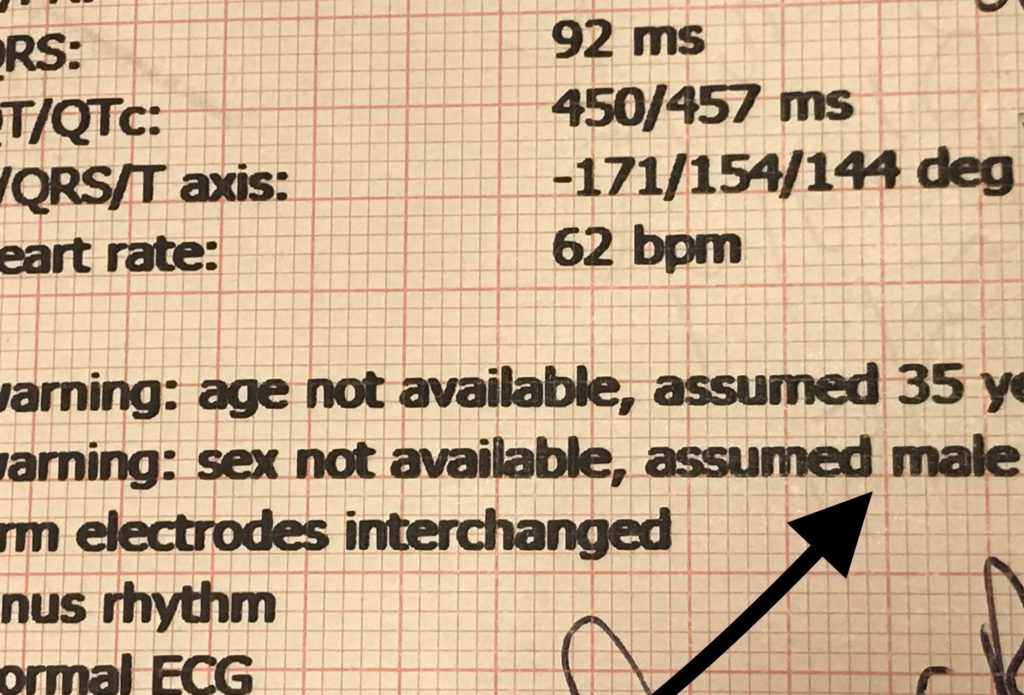

Evidence of the pervasive male bias: we’ve programmed our machines to assume patients are male.

At the recent American Heart Association EPI/Lifestyle conference, a woman-led team from Boston Children’s Hospital presented their work on perceptions of cardiovascular risk among adolescent and young adult (AYA) women. The team recognized that young women didn’t seem particularly informed about or interested in their heart health. Based on this clinical insight, they designed a study to identify barriers to awareness and preventive behaviors among AYA women. I spoke with Courtney Brown, an early-career professional herself and the first author of the abstract3, who explained the team’s findings. First, noted Brown, AYA women have a low baseline knowledge of their cardiovascular risk— lower than expected. They also face competing demands to focusing on their cardiovascular health, such as limited time and financial resources. One key finding was the role of mental health concerns like depression and anxiety: it’s hard to care about something that might happen to you in thirty years when you’re worried about getting through your next few days. Some participants also noted that eating healthy seems too expensive, and sometimes healthy food just isn’t available. These barriers to healthy behaviors are real! Yet behaviors established in young adulthood tend to persist as we age, so AYA women are at a crucial time in their lives for their heart health.

A key point for intervention development, says Brown, is that lifestyle behaviors (including exercise and high-quality nutrition) that are good for mood are also good for heart health. So while cardiovascular health may not be this group’s priority, they will likely benefit from risk-reducing behaviors in multiple ways.

Delivering the message in the setting of competing demands is tricky— and important. When asked what might facilitate their adoption of heart-healthy behaviors, participants in the study indicated that family was their biggest influence, followed by their health care providers and celebrities (favorites were Drake, the Kardashians, and Beyoncé). They also talked about using Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram to get information and communicate. This is rich data, and it suggests that a “meet them where they’re at” approach is likely to be successful. “We’d love for more people to take up this work— we have more steps to take,” Brown says. “We’d love to create and test materials.” It’s encouraging to see rigorous science targeting the needs of a group that’s often overlooked in cardiovascular research. As the body of evidence grows, perhaps some of the disparities in women’s cardiovascular health will fade.

There are also some great lessons here from a methodological standpoint. This study utilized mixed methods, including online focus groups. Courtney Brown, the researcher from the AYA study, stressed that the qualitative component of the work is highly valuable because it can help researchers develop interventions that will effectively reach the population of interest. “It lets us dig deeper into responses to find out what the unique barriers are and how to reach this population, not just what to tell them”, she says. When so much of existing clinical practice is based on research that excluded women, this approach is very relevant. In a climate where the RCT is king and the p-value determines whether or not a finding is considered significant, qualitative work is often undervalued, but these kinds of studies are crucial in understanding the needs, values, and preferences of patient populations— especially those, such as young women, that have been previously understudied and undertreated.

Have you read (or authored!) any great women’s health studies lately? Try to add some to your reading list!

References:

- Scott, P, Unger, E., Jenkins, M. Southworth, M., McDowell, T., Geller, R., Elahi, M. Temple, R., & Woodcock, J. (2018). Participation of women in clinical trials supporting FDA approval of cardiovascular drugs. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 71(18), 1960-9.

- Lau, E. & Wood, M. (2018). How to we attract and retain women in cardiology? Clinical Cardiology, 41(2), 264-268.

- Brown, C., Revette, A., de Ferranti, S., Liu, J., Stamoulis, C., & Gooding, H. (2019). Heart Healthy Behaviors in Young Women: What Prevents Teens from Going Red? Abstract presented at American Heart Association Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health Scientific Sessions, Houston, TX.

Who is writing what you’re reading? Look at the great mix of people on the AHA early career blogging team!