The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Master Class in Health Inequity

In my course, Social and Economic Determinants of Health Disparities, we spend the semester discussing the complex web of factors rooted in social and economic policies that propagate disparities in health. These include education, employment, housing, broader neighborhood structures and, of course, healthcare. We also contextualize individual and interpersonal health behaviors within those structures. When news of the virus really gained steam in mainstream media, one of my students commented that this was an “inverse disparity”—that predominantly rich, white people who’d vacationed in far-off places were affected. I assured him that as data by race and ethnicity surfaced, we would find minorities bearing the brunt of the burden. Unfortunately, as data began to roll in state-by-state, my prediction was accurate. Further, I knew that this was bigger than who was or wasn’t wearing a mask in public, or of the disproportionate number of minorities with pre-existing conditions that may place them at higher risk. It is about a system that consistently favors the physical, mental, emotional, and financial health of certain sects of the population over others.

When the novel coronavirus came to the US public’s attention just months ago, very few of us expected that our lives would change as much as it has in subsequent months. There were so many uncertainties with this unique virus—its transmission, incubation period, symptoms, and appropriate treatment—that we were left whirling in unpreparedness. US culture, built on the foundational value of individual freedom, found itself at odds with the need to protect a more social interest: stopping the spread.

Our best defensive effort was to stay away from each other, or social distancing—a solution (with all of its benefits) that is fundamentally steeped in privilege. It didn’t account for an invisible, operational background of millions of people who occupy the less educated, often undervalued workforce who, ironically, have come to be regarded as “essential”. There are people who must travel on crowded buses to work elbow-to-elbow in order to feed us, sanitize spaces that we might encounter, and help maintain a semblance of normalcy. While some of those workers may view their efforts as an act of service, there is undoubtedly some life or death decision-making happening. On the one hand, they face the risk of exposure to a potentially deadly virus. On the other hand, they face the equally compelling risk of not being paid if they choose not to show up to work, or if they fall ill. For many, there is really no choice at all: the financial strain posed by the latter and its negative effects on their families is non-negotiable. So, they put themselves in harm’s way, hoping against hope that they won’t contract the virus and/or bring it home to their loved ones.

Although we’re “in this together,” we have left many of the most vulnerable to fend for themselves. They live in food deserts and now have even fewer options at their disposal than before, as those with disposable income and time stocked up on supplies. They are disconnected from accurate, timely information, which is even more important as we learn new lessons about the virus daily. For some, their experience with this pandemic can best be described as “inconvenienced,” while others don the armor of homemade masks to preserve their (and our) lives.

My students are learning the same lessons many are starting to awaken to: when systems fail, the marginalized become more marginalized. The pandemic operationalizes the very definition of “disparities” that we discussed during the first lecture. We are all seeing that “differences rooted in social disadvantages that further expose individuals to additional disadvantage” mean that those who are the least equipped with the resources to withstand a pandemic are placed at higher risk of exposure, unable to effectively employ best-practices for protection against an unpredictable virus. The novel coronavirus has set the stage for a master class in health inequity and demands that we pay attention to the socially and racially stratified patterns emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. Luckily, experts have provided a game plan for helping the most vulnerable. Hopefully, this experience will build our empathy towards the overlooked among us as we tackle health inequity together.

Class is in session.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

Figure 1: 3-D CT-FFR coronary tree showing both flow limiting and non-flow limiting lesions [from reference 1].

Figure 1: 3-D CT-FFR coronary tree showing both flow limiting and non-flow limiting lesions [from reference 1].

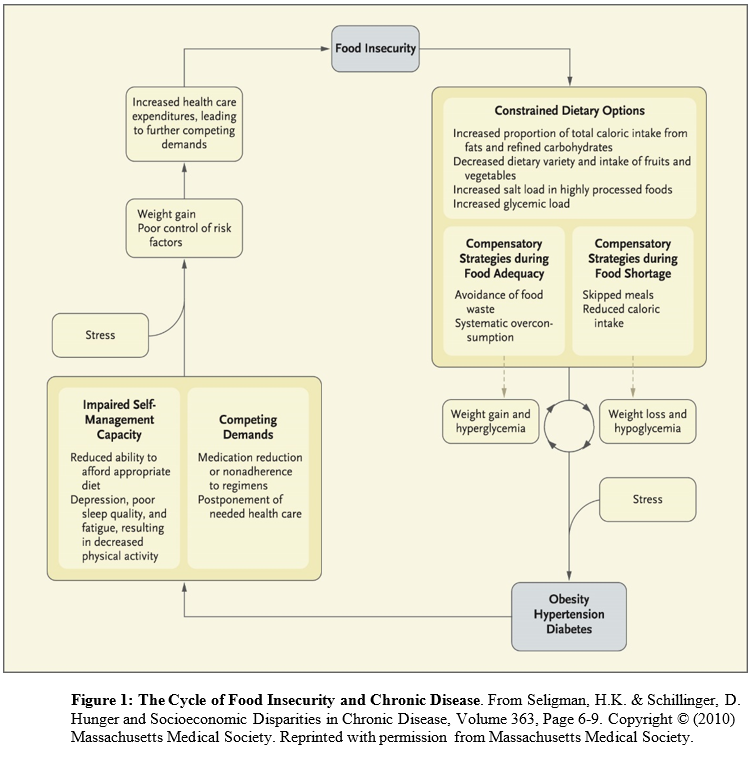

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.

Conceived of as a cyclical process (in which people have periods fluctuating between food adequacy and inadequacy), fewer dietary options lead to increased consumption of cheap, energy dense, but nutritionally poor foods. Over-consumption of these foods during periods of food adequacy can lead to weight gain and high blood sugar, and reduced consumption of food during food shortages can lead to weight loss and low blood sugar. These cycles are exacerbated by stress and result in obesity, high blood pressure, and ultimately diabetes and coronary artery disease. The cycle continues until access to adequate, safe, high-nutrition foods stabilizes.