When it comes to survival of out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), many advances have been made over the years, 1 early and high-quality chest compressions and defibrillation are key components of this. However, even prior to coronavirus and COVID-19, many bystanders are still hesitant to perform CPR for a variety of reasons; fear of litigation, fear of causing harm, or due to concerns about infectious disease transmission.2 In the new age of social distancing and a highly infectious disease causing stress on our world, the hesitancy may increase. In addition, many programs who have been key in providing education, such as CPR training, have come to a halt during this time.

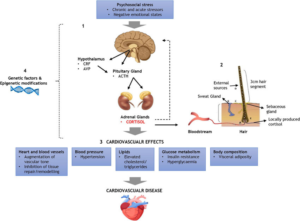

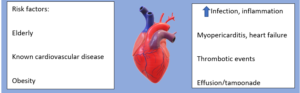

CPR is generally considered an “aerosolized” procedure, 3 a procedure conveying high risk of transmission of disease via respiratory droplets. Resuscitation efforts in and out of hospital require multiple people in close proximity to each other to respond. In addition, COVID-19 has been reported to cause myocardial injury and ventricular arrhythmia that may predispose someone to cardiac arrest, 1 and despite a pandemic, sudden cardiac arrest and other causes of death do not decline. A concern rising in the medical community since shelter-in-place laws and changing stresses on our medical system, is a notable decrease in visits to the Emergency Departments for common complaints and concerns, such as chest pain, syncope and other things that may dispose someone to a cardiac arrest. We need to be aware of this happening in the community and the potential need for lay and EMS response in these situations.

Lay persons and dispatchers play a key role in survival efforts, such as initiating CPR and early defibrillation. There has been documented success with telephone CPR and CPR guidance by dispatchers. An important component of ensuring the best survival of the community and those with COVID-19 or potential COVID-19 is communication and a well-developed community plan to ensure timely and quality resuscitation to patients while protecting rescuers. Recently, Circulation has released Interim Guidance and Advanced life Support in Adults, Children, and Neonates with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19,1 a quick review is here. Resources from King County EMS in Washington are available for establishing a community response and plan here.

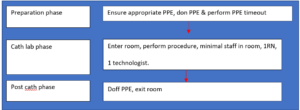

Overall, the common themes are aimed at adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), reducing the number of people responding to an event, and in the case of OHCA for lay people, focusing on hands-only CPR.

For lay persons, the majority of SCA occurs at home. The likelihood of already being exposed to a household contact is high and should be considered when responding to an arrest; for adults hands-only CPR with high-quality compressions is encouraged with early activation of EMS and defibrillation(not an aerosolizing procedure), if available. In the case of pediatric resuscitation, due to the high likelihood of respiratory arrest causing cardiac arrest, it is advised that if willing, after weighing the risk and benefit, that rescue breaths are provided along with compressions. You may use a cloth or mask covering over the victim’s mouth to help reduce transmission in the event it is not a household member.1

For EMS providers, dispatch is crucial in screening calls for any possible risk of exposure to COVID-19, based on symptoms in the victim or any recent contact or household members, and advising whether doing PPE is recommended to the EMS team.1 In Seattle, they have shown a very low rate of transmission to EMS providers when wearing the appropriate PPE.4

For in-hospital cardiac arrest, it is again important to reduce the personnel involved in the resuscitation, close the door when possible, and consider adding PPE to the code carts. It is also important to use HEPA filters and closed circuit ventilation strategies when it comes to ventilation. The guidance also encourages early intubation by the provider with the highest qualification with the best chance for successful intubation, and use video laryngoscopy when able to minimize aerosolizing the virus while securing a closed circuit airway. The guidance also suggests that if patients are prone and intubated to perform CPR without moving the patient in the standard T7-10 vertebral bodies, however, if they are not intubated to attempt to place them supine and proceed with resuscitation.1

The article also discusses the importance of clarifying goals of care and advanced directives upon arrival, as well as proposes a careful evaluation in the cases of out of hospital cardiac arrest with inability to obtain ROSC, suggesting in some cases, this may be a reason to avoid transport to the hospital due to low likelihood of survival. However, it is important to take into consideration with the benefit, risk and ethics involved.1, 3

Another important update is in regards to maintenance of certification such as BLS/ACLS/PALS. As of March 13, the AHA has offered a 60 day extension for instructor cards and also recommends extension of provider cards for the same length, this allowance is open to be extended based on the evolving threat and CDC/public health recommendations, read the statement here. 5

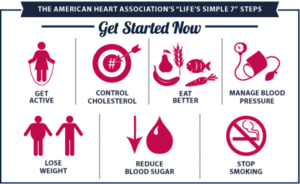

Many people are looking for things to do in this time of sheltering in place, perhaps this could be an opportunity for education and learning on CPR and AED’s. There are many online resources available, and with the advent of telemedicine, zoom learning and video visits increasing, perhaps we could use this as an opportunity to increase our virtual presence for CPR education.

If you’re interested in some online resources, check out the ILHR website, or your local education center’s website.

- Edelson, Dana P, et al. “Interim Guidance for Life Support for COVID-19.” Circulation, ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047463.

- Scquizzato, Tommaso, et al. “The Other Side of Novel Coronavirus Outbreak: Fear of Performing Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.” Resuscitation, vol. 150, 2020, pp. 92–93., doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.03.019.

- Defilippis, Ersilia M., et al. “Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A View from Trainees on the Frontline.” Circulation, Sept. 2020, doi:10.1161/circulationaha.120.047260.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”