Moving from ‘Luck of the Draw’ to making BLS and Defibrillator availability basic

The AHA ReSS council had a fascinating 2021 meeting, including trials making us reassess the optimal temperature for patients following cardiac arrest (TTM2) and those investigating the potential new application of existing meds repurposed to cardiac arrest (e.g. Tocilizumab [IL-6 inhibitor] to reduce cytokine storm post-arrest, LPC-DHA to improve mitochondrial function). What really put these clinical trials into perspective was the plenary session, featuring actual survivors of sudden cardiac arrest discuss their experiences with the frustrating lack of established resources as they journey to find the new normal for their lives.

Perhaps the most memorable part of AHA 2021 was the harrowing account of Dr. Kevin Volpp, a cardiology and behavioral economics researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, reflect on his own sudden cardiac death experience. The morning of July 9, 2021 started as just a regular day. Volpp traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio to watch his daughter, Anna, play in a squash tournament. While dining with Anna, her Coach (Gina Stoker), and her Coach’s boyfriend (John White) the night before, Volpp suddenly became unresponsive, slumping his chair into the arms of White. Coach Stoker called 911. White, who is himself a squash coach at Drexel University, laid Volpp flat, could not find a pulse, and initiated bystander CPR. EMS arrived four minutes later. Ultimately, he received 14 minutes of CPR with three shocks from the automated external defibrillations before his circulation was restored. He was rushed to University of Cincinnati Hospital, where he was found to have a 99% blockage in his LAD artery, which was opened and stented (1).

Volpp, who had a strong family history of premature heart attacks, had been undergoing primary prevention measures including CAC screening, medications, and well exceeding the AHA’s minimum recommendation for weekly exercise, as he was training with Anna for an Ironman 70.3 triathlon (1). Sudden cardiac death does not always occur in those with a strong family history with plaque in their arteries. During his 3rd year of internal medicine residency, Dr. Anezi Uzendu suffered cardiac arrest while he was playing basketball, with no prior family history. Fortunately, through high quality CPR and persistent resuscitation (receiving a total of 13 defibrillation attempts before he was revived!)(2), he eventually recovered and completed both general and interventional cardiology fellowships.

Ultimately, the prompt recognition and initiation of the cardiac chain of survival that allowed Drs. Volpp and Uzendu to have good outcomes. Coach White credited Drexel University’s requirement that Coaches keep their training in Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) active (1). BLS is the use of high-quality chest compressions (2 inches deep at 100-120 beats per minute) to maintain adequate circulation to the brain, before additional help can arrive to provide higher level of care (ACLS). Out of hospital cardiac arrest and recovery is far from normal across the country, occurring in less than 8% of individuals (3). Acknowledging the critical nature of illnesses causing cardiac arrest, why do so few survive? Low rates of education and implementation of bystander CPR and AEDs, two of the most important interventions linked to improving survival by as much as 3-fold (3). These interventions are not independent, as defibrillator effectiveness increases, with increasing quality of CPR (optimal depth & speed) administered (4). In 2014, Dr. Monique Anderson and colleagues at Duke University found that, only 1.29-4.07% of the US population is certified in BLS—a shockingly low statistic for the number one cause of death in America (heart disease) (3, 5). Unfortunately, disparities are more likely in racial minority, older, rural, and Southern communities (5). Dr. Maryam Naim and colleagues found similar disparities in a pediatric population (6). Not surprisingly, average rates of bystander in America CPR are only 38.2% (7), with significant geographic variation (10-65%) (8) and lower rates of proper technique (compression depth of 2 inches and pace of 100-120 beats per minute (9). These findings are compounded by the fact that almost 90% of cardiac arrests occur in or near the home (10).

What’s the best method of increasing this? Anywhere from 71.5% to 85.3% of American high school seniors have their driver’s license (11). Many obtain this through taking driver’s education class in school. One long term solution would be providing BLS courses to all high schoolers, with the option to advance to ACLS certification for those interested. While logistics can be debated, this would increase the proportion of individuals ready to perform by stander CPR from the 70% of Americans who don’t feel prepared (10) to adequately administer CPR. For adults, there are many available BLS courses available. The AHA Knowledge Booster App is a fun and interactive resource for those who want to learn more, but don’t know where to start. There are several Spotify playlists of songs with a tempo of 100-120bpm (12-14), but “Staying Alive,” by the Bee gees seems to be the most enduring. Dr. Uzendu founded an organization—Make BLS Basic—that focuses on increasing bystander CPR rates in minority communities (15).

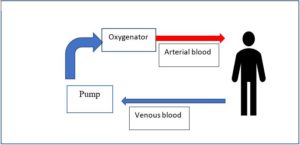

Increasing bystander CPR rates is only half of the prehospital equation. When bystanders perform CPR and use a defibrillator, the survival to hospital discharge approaches 50-60%, with improved survival and neurological outcome with earlier defibrillation of shockable rhythms (3). The meager rates of Automated External Defibrillator (AED) availability in public spaces are similarly shocking. In a Cleveland Clinic survey, only 27% of Americans reported an AED in their workplace. After his experience, Volpp posed the question, should national chains be required to install AEDs, given that most adults spend 15-20 (pre-pandemic) minutes a day in a restaurants or bar (1). To be sure, AEDs require maintenance (replacement of defibrillator pads & batteries) and untrained lay providers may struggle to use them effectively (3). Several cost-effectiveness analyses have found a benefit of widespread dissemination of public AEDs (16-18), though not all are as optimistic (19, 20). AED Laws vary by state (21); there has also been federal legislation (22). The Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation states a goal of having an AED accessible within 90 seconds of any public area that people congregate (e.g. schools, state & federal buildings, casinos, etc.). We are far from this important goal.

I think the ultimate questions are: Should one’s survival following cardiac arrest depend on being with the right person at the right time or where you live, shop, eat, or pursue leisure? Will we accept the status quo? How can we improve rates of bystander CPR and AED availability to give everyone an equitable chance at surviving these life-threatening events, and a new lease on life? How can we better support SCA survivors during their recovery? Looking forward to answering these questions at future meetings.

References:

- Avril T. “A Penn professor’s heart stopped at restaurant that had no defibrillator. Few are equipped with the lifesaving devices.” Philadelphia Inquirer. 2021. https://www.inquirer.com/health/aed-defibrillator-restaurant-cardiac-arrest-20211213.html

- Uzendu A. From “delivered to the cath lab alive” to Interventional Cardiologist on call in 5 years. God is good. #CPRSavesLives. In: @DrUzendu, editor. 2021. https://twitter.com/DrUzendu/status/1465120531317989382

- Brady WJ, Mattu A, Slovis CM. Lay Responder Care for an Adult with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(23):2242-51.

- Edelson DP, Abella BS, Kramer-Johansen J, Wik L, Myklebust H, Barry AM, et al. Effects of compression depth and pre-shock pauses predict defibrillation failure during cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2006;71(2):137-45.

- Anderson ML, Cox M, Al-Khatib SM, Nichol G, Thomas KL, Chan PS, et al. Rates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):194-201.

- Naim MY, Griffis HM, Burke RV, McNally BF, Song L, Berg RA, et al. Race/Ethnicity and Neighborhood Characteristics Are Associated With Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Pediatric Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the United States: A Study From CARES. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(14):e012637.

- Promotion OoDPaH. Increase the rate of bystander CPR for non-traumatic cardiac arrests — PREP‑01. In: Promotion OoDPaH, editor.: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/emergency-preparedness/increase-rate-bystander-cpr-non-traumatic-cardiac-arrests-prep-01/data

- Brown LE, Halperin H. CPR Training in the United States: The Need for a New Gold Standard (and the Gold to Create It). Circ Res. 2018;123(8):950-2.

- New Cleveland Clinic Survey: Only Half Of Americans Say They Know CPR [press release]. Newsroom: Cleveland Clinic, February 1, 2018 2018. https://newsroom.clevelandclinic.org/2018/02/01/new-cleveland-clinic-survey-only-half-of-americans-say-they-know-cpr/

- CPRBlog [Internet]. www.heart.org: American Heart Association. [cited 2021]. https://cprblog.heart.org/cpr-statistics/

- Ranzetta T. Question of the Day: What percent of high school seniors have a driver’s license? : Next Gen Personal Finance; 2019 [Budgeting]. Available from: https://www.ngpf.org/blog/budgeting/question-of-the-day-what-percent-of-high-school-seniors-have-a-drivers-license/.

- American Heart Association. Hands-Only CPR’s ‘Keep The Beat’ 100BPM Playlist: Spotify; 2015. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/18uMyHJHboUUCCwbtwdj3k

- nyphospital. Songs to do CPR to: Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7oJx24EcRU7fIVoTdqKscK

- seigfriedb. CPR playlist (110 bpm). https://open.spotify.com/playlist/67BxVmgXqjr2lQqXKsyLxw: Spotify.

- Uzendu A. Make BLS Basic http://www.makeblsbasic.org2019 [Available from: http://www.makeblsbasic.org.

- Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Granfeldt A, James LP, Caulley L. Cost-effectiveness of public automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation. 2019;138:250-8.

- Nichol G, Huszti E, Birnbaum A, Mahoney B, Weisfeldt M, Travers A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of lay responder defibrillation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(2):226-35.e1-2.

- Weisfeldt ML, Sitlani CM, Ornato JP, Rea T, Aufderheide TP, Davis D, et al. Survival after application of automatic external defibrillators before arrival of the emergency medical system: evaluation in the resuscitation outcomes consortium population of 21 million. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(16):1713-20.

- Atkins DL. Realistic expectations for public access defibrillation programs. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16(3):191-5.

- Pell JP, Walker A, Cobbe SM. Cost-effectiveness of automated external defibrillators in public places: con. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22(1):5-10.

- Roszak AR. CPR / AED Laws: Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation; [Available from: https://www.sca-aware.org/about-sudden-cardiac-arrest/cpr-aed-laws.

- State Laws on Cardiac Arrest and Defibrillators National Conference of State Legislatures [cited 22 Dencee. Available from: https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/laws-on-cardiac-arrest-and-defibrillators-aeds.aspx.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”