How will COVID-19 Affect Return to High School Sports and ECG Screening?

August is traditionally very busy month in the pediatric cardiology office; visits for “sports clearance” flood the schedule due to something picked up on a high school sports physical such as chest pain. Most of these will be non-cardiac and receive reassurance; however, the cardiac causes in the pediatric population can be quite distressing. With the current COVID-19 pandemic we are seeing many cardiac effects of the virus— myocardial inflammation, dysfunction and coronary artery dilation or MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children). There has also been a reported increase in out of hospital cardiac arrest in the adult population, which could be attributed to those afraid to seek care, but none the less, a concern.

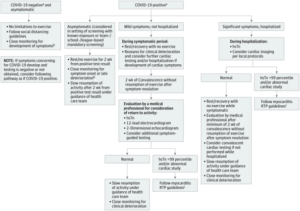

Cardiac effects play an important part in the recent discussions on return to school, as eventually return to school will mean return to school sports. Sports cardiologists have been following this closely and have been working to establish a safe way for return to sports in competitive athletes who have had COVID-191(click here for recommendations and see flowchart below), which may include extensive cardiac testing of those who had symptomatic COVID-19, most of which is based on the return to play myocarditis guidelines.2 These important decisions require individualization, knowledge of risk and what is happening in the community.

So what does this mean for the high school athletes? There is no doubt that exercise is great for everyone, especially with the rising obesity and the sedentary lifestyle. Organized sports participation has shown to have a positive impact on mental and physical health that extends beyond childhood.3 Many have raised concerns about the development and health of children by not attending school, along with decrease in social interaction and activity from organized sports during the stay-at-home orders and while we work to defeat COVID-19 spread.

Prior to the pandemic, the question of universal ECG testing for high school athletes always started a conversation, but could that change? Critics say that the false positives create distress and extra healthcare cost, that follow up is problematic and that it has not been shown to change outcomes. Others argue saving one child from the devastating event of collapsing and dying on the field is worth it, and a recent study showed ECG with H&P is more likely to detect a condition associated with sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) than H&P alone, and also improved cost efficiency when interpreted in the right hands.4 All agree it is important to have a good plan in place for SCA at all sporting events, including an emergency response plan in place specific to cardiac arrest.

With so many affected by the virus, at varying severity, I can’t help but wonder if this will change the way we assess our young athletes for participation in sports when it is safe to do so. While healthcare costs are always a problem, with a new virus and unclear long-term outcomes, we must be conservative. Perhaps this may provide an opportunity to learn more about ECG screening, as we will likely see a larger amount of patients who have had COVID-19 coming to our offices for clearance. This may provide an opportunity to gather evidence on the continued debate of whether ECG screening is effective.

Until we know more, what we do know is it is safer to be conservative, to assess benefit and risk and provide appropriate counseling to families on signs and symptoms of SCA. We also must continue to reassess and stay up-to-date on new knowledge and testing related to COVID-19 recovery and sports. Most importantly, it is important that we continue to advocate for heart safe schools which include having AEDs, training in CPR, and emergency response plans related to Sudden Cardiac Arrest. With more kids participating in school from home, this could be a great opportunity to engage the whole family in CPR and AED education to improve the safety and survival of our communities and at home.

References

- Phelan, Dermot, et al. “A Game Plan for the Resumption of Sport and Exercise After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection.” JAMA Cardiology, 2020, doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2136.

- Maron, Barry J., et al. “Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 3: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy and Other Cardiomyopathies, and Myocarditis.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 66, no. 21, 2015, pp. 2362–2371., doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.035.

- Logan, Kelsey, and Steven Cuff. “Organized Sports for Children, Preadolescents, and Adolescents.” Pediatrics, vol. 143, no. 6, 2019, doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0997.

- Harmon, Kimberly G, and Jonathan A Drezner. “Comparison of Cardiovascular Screening in College Athletes” Heart Rhythm, 2020, www.heartrhythmjournal.com/article/S1547-5271(20)30406-9/pdf.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”