The darkness before the dawn–Long COVID is lurking around

As we are starting to live with the facts that COVID-19 is not leaving us any time soon, sense of danger and urgency start to fade away. More than two years have passed, we have made great strides in combating the pandemics. With advanced technologies, vaccine and antiviral drug developments provide us potential means out of this seemingly never-ending battle. Viruses constantly change through mutation. While Delta variant is phasing out, Omicron variant begins its domination globally. Current research suggest that Omicron variant is less deadly compared to the Delta variant, especially to fully vaccinated people. However, the high spread rate of Omicron variant is a major concern to the public.

Some of us may wonder, it might not be a big deal. Since most evidence suggest that the symptoms of fully vaccinated patients are rather minor, especially the chance of suffering severe symptoms if you had a booster shot is even less. After a few days discomfort, you might end up obtaining better immunity after building up antibodies through infection. It might be partially true to some people. However, some unlucky ones continue to suffer from post-COVID conditions even after four or more weeks. These post-COVID conditions are also known as long COVID, long-haul COVID, post-acute COVID, long-term effects of COVID, or chronic COVID.

What is long COVID?

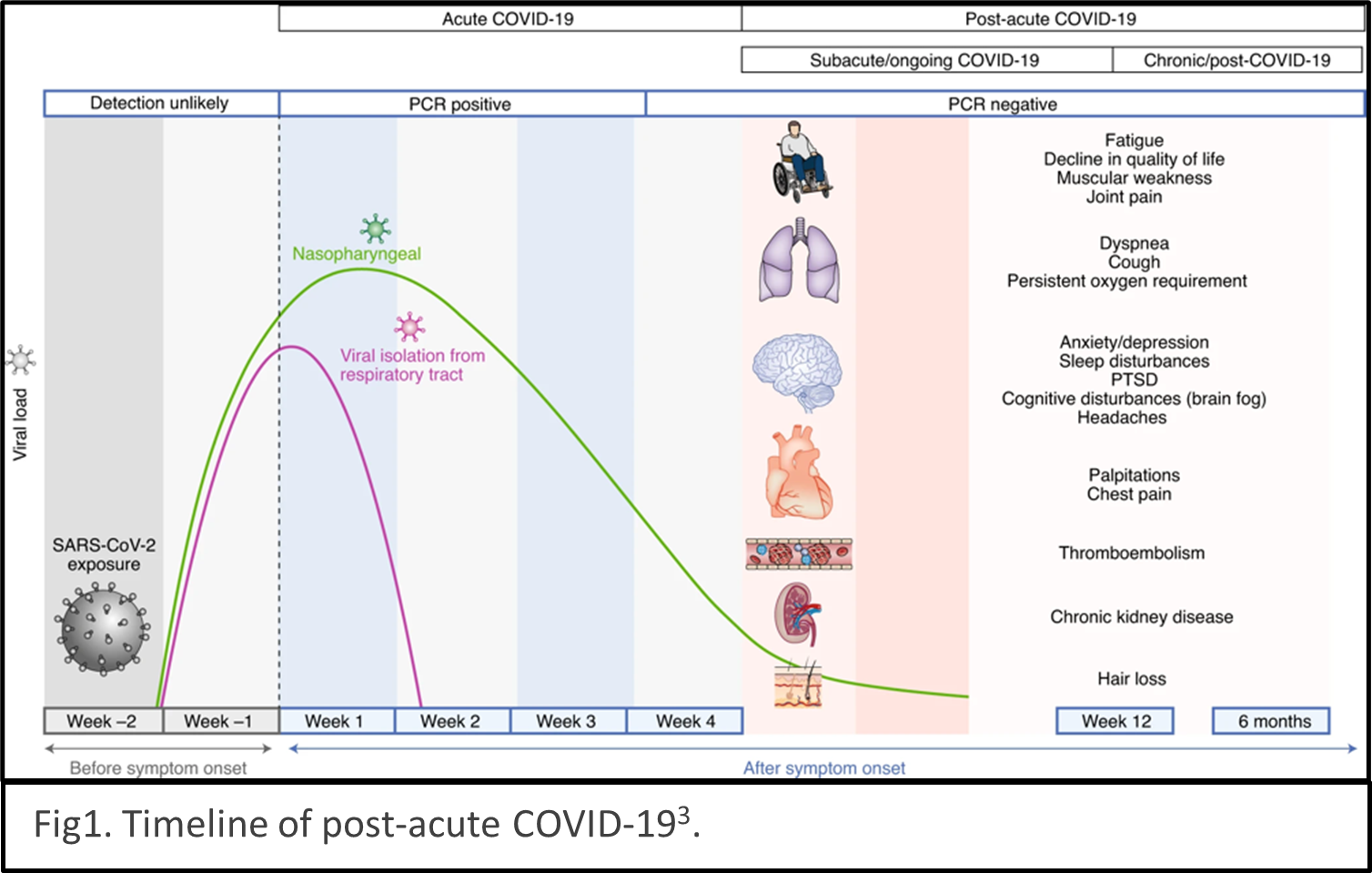

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), long COVID describes the condition as sequelae that extend beyond four weeks after initial infection1. The timeline of post-acute COVID-19 shows as Fig1. The list of common symptoms of post-COVID conditions is growing. Symptoms which people commonly report include difficulty breathing, fatigue, brain fog, cough, chest/stomach pain, headache, heart palpitations, muscle pain, diarrhea, sleep problems, fever, lightheadedness, rash, mood changes, changes in smell or taste, and changes in menstrual period cycles2,3. The challenges of diagnosing long COVID are multiple layers. The social isolation resulting from pandemic prevention measures can cause mental health stress such as depression, anxiety, and mood changes. Complications of pre-existing conditions may unmask after COVID infections.

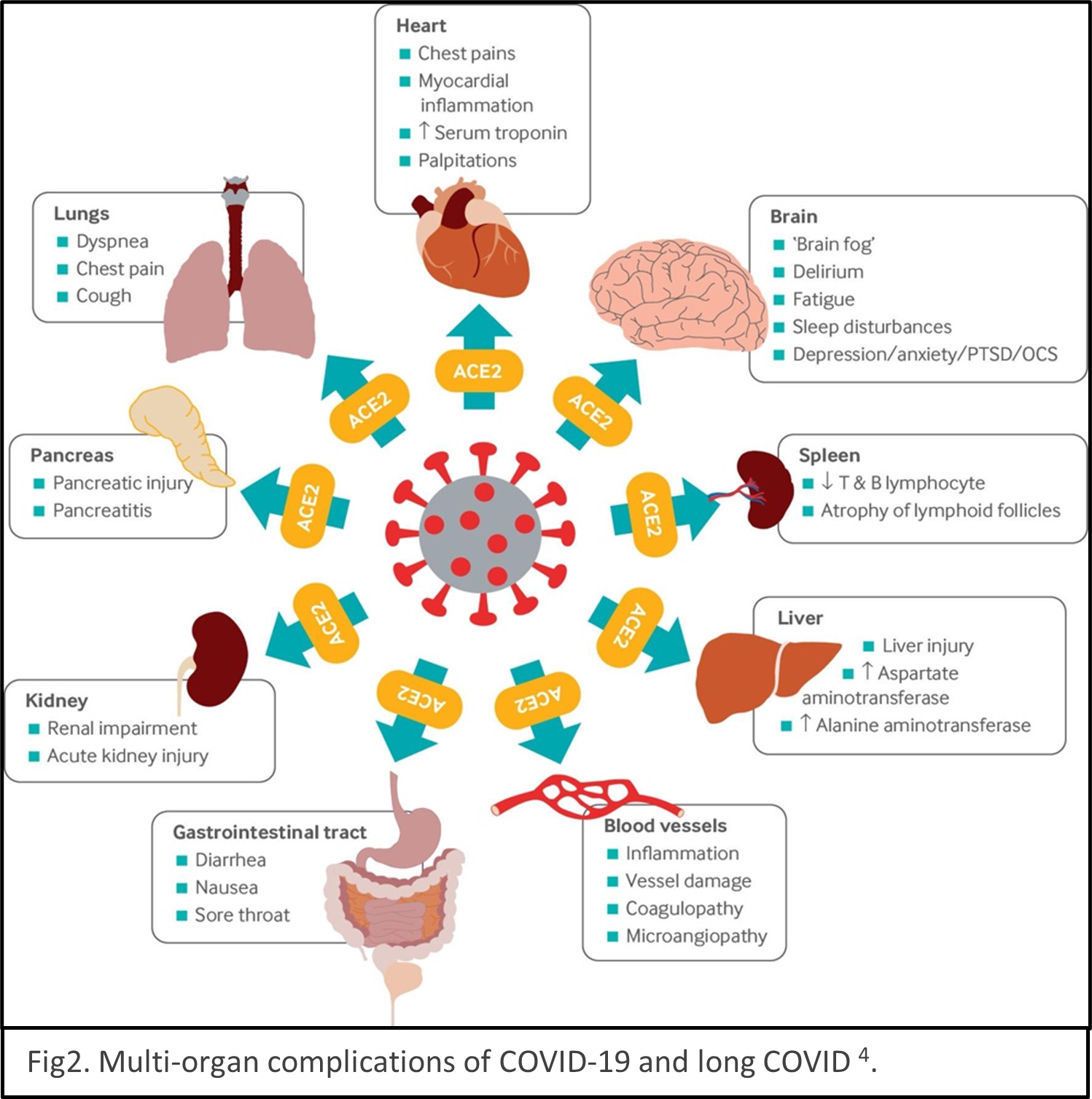

describes the condition as sequelae that extend beyond four weeks after initial infection1. The timeline of post-acute COVID-19 shows as Fig1. The list of common symptoms of post-COVID conditions is growing. Symptoms which people commonly report include difficulty breathing, fatigue, brain fog, cough, chest/stomach pain, headache, heart palpitations, muscle pain, diarrhea, sleep problems, fever, lightheadedness, rash, mood changes, changes in smell or taste, and changes in menstrual period cycles2,3. The challenges of diagnosing long COVID are multiple layers. The social isolation resulting from pandemic prevention measures can cause mental health stress such as depression, anxiety, and mood changes. Complications of pre-existing conditions may unmask after COVID infections. Reinfection of COVID could be mistaken as persistent symptoms. Multiple organs are reported being the victims of SARS-CoV-2 infection, for example, lungs, heart, brain, kidney, spleen, liver and the cardiovascular systems4 (Fig2). Some people have severe illness with COVID experience combinations of multiorgan effects or autoimmune conditions with symptoms lasting for weeks or months after initial infection. Long COVID is a serious concern. We just begin to understand it, and the path to be able to treat it with ease is winding.

Reinfection of COVID could be mistaken as persistent symptoms. Multiple organs are reported being the victims of SARS-CoV-2 infection, for example, lungs, heart, brain, kidney, spleen, liver and the cardiovascular systems4 (Fig2). Some people have severe illness with COVID experience combinations of multiorgan effects or autoimmune conditions with symptoms lasting for weeks or months after initial infection. Long COVID is a serious concern. We just begin to understand it, and the path to be able to treat it with ease is winding.

Various guidelines have been established focus on treating and managing COVID5,6 and long COVID7. While the guidelines will undoubtedly improve as new evidence comes to light. The etiology, mechanism, and consequences of COVID and long COVID remain elusive currently. Large epidemiology studies are undergoing to help us understand mechanisms and develop targeted treatments. American Heart Association just establishes a new funding program to invite more researchers to study the mechanisms underlying cardiovascular consequences associated with COVID-19 and long COVID in January 2022. Scientific communities are racing to understand COVID and long COVID.

The COVID pandemics is a serious public crisis. Although the situation may seem be getting better, healthcare staff shortages caused by pervasive Omicron variant infections and the lack of rapid COVID tests are posing imminent danger to the public healthcare system. Moreover, the effects of long COVID vary person by person, it’s better to stay vigilant and not get infected than taking it callously and passing it to vulnerable people unintentionally.

REFERECE

- Datta SD, Talwar A, Lee JT. A Proposed Framework and Timeline of the Spectrum of Disease Due to SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Illness Beyond Acute Infection and Public Health Implications. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2251–2252.

- Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259–264.

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan M V, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine. 2021;27(4):601–615.

- Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid–mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-1

- National Institute of Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 NICE guideline; c2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188