The Needle Moves Slowly on MINOCA

I remember being a medical student and listening to a podcast where I first heard the term MINOCA (myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries) in 2019. I was deciding between internal medicine and OBGYN at this time, and learning about heart disease specific to and common in women naturally grasped my attention. Dr. Bairey Merz from Cedars-Sinai provides a fantastic overview of the disease process and evaluation. I kept thinking about all the ways we’ve made incredible strides in heart disease over the years. Now, I was thinking they were unequal.

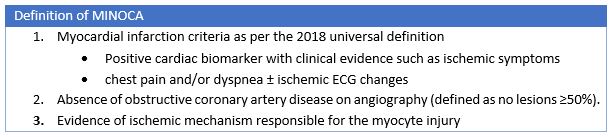

Dr. Brent Gudenkauf, a PGY-2 at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, et al. recently published a review in the Journal of the American Heart Association entitled “Role of Multimodality Imaging in the Assessment of Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: Beyond Conventional Coronary Angiography”1. They do a wonderful job of taking us through diagnostic criteria, preferred imaging modalities, and guideline recommendations regarding MINOCA. This term is still not commonplace outside of cardiology, and in the early days some thought these patients were having “false positive MIs” as they outline in the paper. This led to mostly women missing out on necessary diagnostic work up and targeted therapies. Today we have specific diagnostic criteria from the AHA and ESC including positive serum myocardial biomarkers and clinical evidence of MI (which can include ischemic symptoms, new ST segment changes, new LBBB, new pathologic Q waves among others) and no epicardial coronary lesions >50% stenosis on angiography.2,3

What I find disheartening is how slowly our needle has moved in terms of therapies. As they highlight in this paper, even after diagnosis of MINOCA 25% of patients continue to experience angina5 and experience worse quality of life compared with MI-CAD (MI associated with obstructive coronary artery disease) due to persistent anginal symptoms and inadequate treatment with existing antianginal therapies. They were less often treated with beta blockers and less often referred to cardiac rehab5. It is clear that this patient population of majority young women is faring worse than its traditional myocardial infarction counterpart in terms of therapies and quality of life.

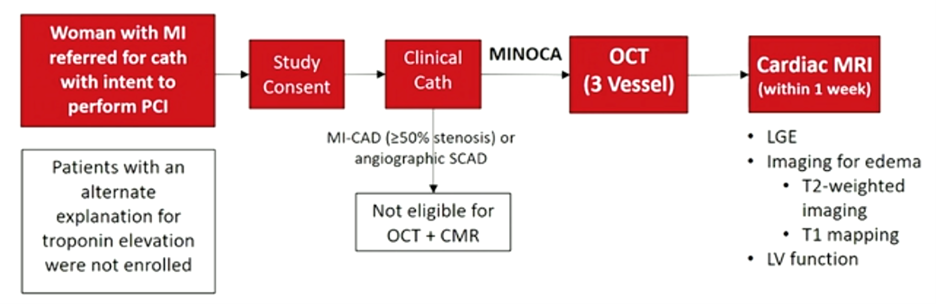

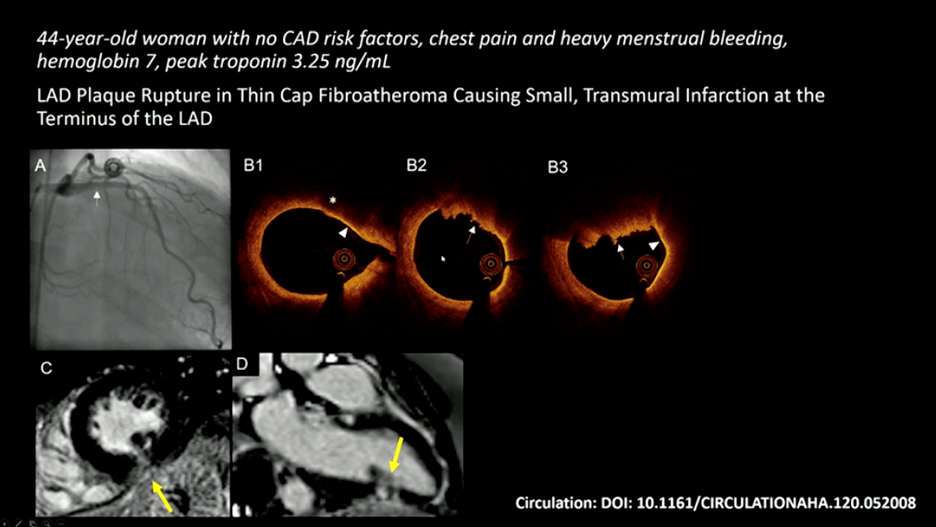

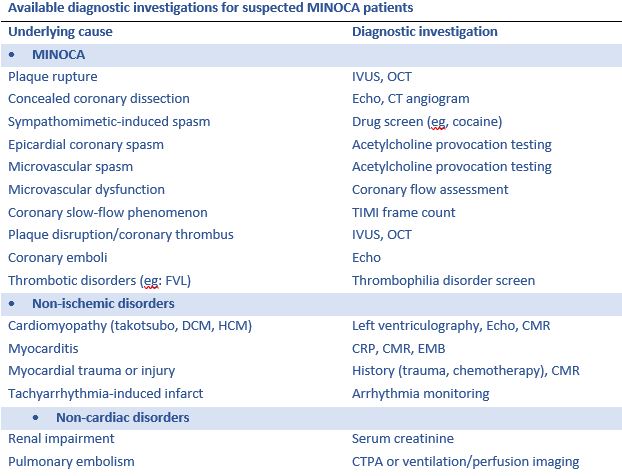

For these reasons, we should all develop a good understanding of diagnostic pathways and targeted treatments. The recommended imaging modality is IVUS (intravascular ultrasound) or OCT (optical coherence tomography) 2,4. As a young trainee myself, I am not familiar with either of these modalities and was introduced to these concepts via #AHA21. OCT is an optical analogue of IVUS and can “differentiate tissue characteristics such as fibrous, calcified, or lipid-rich plaque and identify thin-cap fibroatheroma”6. During PCI, OCT can also provide information about dissection, tissue prolapse, and thrombi6; this is significant given SCAD (spontaneous coronary artery dissection), in situ thrombosis, and epicardial and microvascular spasms are all causes that can lead to MINOCA1. Cardiac MR is also useful when MINOCA is suspected as it will show late gadolinium enhancement and can also uncover mimics like myocarditis and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Additionally, if embolism to coronary arteries is suspected then thrombophilia workup is recommended. They do a wonderful job outlining this algorithm in Figure 2 in the paper by Gudenkauf et al.1 We should all be working to familiarize ourselves with this figure and its recommendations and integrating this into our evaluation for chest pain.

Although the advancements in diagnosis and evaluation are exciting and important, there are no randomized clinical trials evaluating treatments for patients with MINOCA. The MINCOA-BAT trial is an upcoming randomized multi-center study which will hopefully help to move the needle forward in evidence-based targeted therapies (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT 03686696). This excellent review by Gudenkauf et al should be shared widely as this is an important and still too often underdiagnosed and undertreated condition among our patients.

References

- Gudenkauf, B., Hays, A. G., Tamis‐Holland, J., Trost, J., Ambinder, D. I., Wu, K. C., Arbab‐Zadeh, A., Blumenthal, R. S., & Sharma, G. (2021). Role of multimodality imaging in the assessment of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries: Beyond conventional coronary angiography. Journal of the American Heart Association. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.022787

- Tamis‐Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, Agewall S, Brilakis ES, Brown TM, Lerman A, Cushman M, Kumbhani DJ, Arslanian‐Engoren C, et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of patients with myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019; 139:e891–e908. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000670

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

- Agewall S, Beltrame JF, Reynolds HR, Niessner A, Rosano G, Caforio AL, De Caterina R, Zimarino M, Roffi M, Kjeldsen K, et al. ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non‐obstructive coronary arteries. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:143–153. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw149

- Grodzinsky A, Arnold SV, Gosch K, Spertus JA, Foody JM, Beltrame J, Maddox TM, Parashar S, Kosiborod M. Angina frequency after acute myocardial infarction in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2015; 1:92–99. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcv014

- Terashima, M., Kaneda, H., & Suzuki, T. (2012). The role of optical coherence tomography in coronary intervention. The Korean journal of internal medicine, 27(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2012.27.1.1.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”