As a new member of the Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research (QCOR), I’m excited to attend the annual Scientific Sessions in Arlington, Virginia on April 5-6, 2019. QCOR 2019 Scientific Sessions is put on in collaboration with the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Stroke Council, and of course, the Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research.

Apart from reviewing the programming and online resources, I’m not sure what to expect so I turned to QCOR colleagues and leadership who could give me the lowdown.

Key Takeaways

- The QCOR Scientific Sessions bring together a diverse group of clinicians, researchers, and policymakers interested in healthcare quality and patient outcomes.

- Both days of the conference are packed with dynamic workshops, early career lunches and panels, impactful plenary sessions, and opportunities for networking.

- Early career development is a major focus of the QCOR conference, highlighted by the coveted Young Investigator Award finalist oral abstract sessions and early career panel discussions.

- Follow along at #QCOR19 on Twitter with hashtags #CQOMeetingReport and #QCOR19 as we live tweet from the sessions.

Let me introduce Drs Madeline Sterling, Boback Ziaein, Collene McIlvennan, and Tracy Wang.

- Madeline Sterling, MD MPH MS, (@mad_sters) is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine Division of General Internal Medicine.

- Boback Ziaeian, MD PhD FACC FAHA, (@boback) is an Assistant Professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA in the Division of Cardiology.

- Colleen McIlvennan, DNP MS BSN (@colleenkmac) is an Assistant Professor of Medicine-Cardiology and Lead Nurse Practitioner in advanced heart failure and transplantation at University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is also the chair of the QCOR Young Clinicians and Investigator Committee.

- Tracy Wang, MD MHS MS (@TYWangMD) is an Associate Professor of Medicine, a member of the Duke Clinical Research Institute, and Director of Health Services and Outcome Research at Duke.

Dr. Colleen McIlvennan

Dr. Madeline Sterling

Dr. Tracy Wang

Dr. Boback Ziaeian

What is the QCOR council all about?

In an AHA newsletter, QCOR Council Chair, Tracy Wang, presents 3 reasons to join QCOR:

- QCOR focuses on real world health care issues and practical solutions

- QCOR is disease and specialty agnostic – if you study the heart, brain, disparities, health systems, or anything else, you belong in QCOR

- In QCOR, you can connect with a growing community of creative, passionate, and fun people who want to influence health and healthcare delivery in a positive way

QCOR is not only a place for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers to come together for healthcare quality and patient outcomes, but is also focused particularly on early career development.

Dr Tracy Wang commented that the QCOR “council has always been proud of its diverse constituency; and [its] collaborations bring to the forefront experienced multidisciplinary teams and stakeholders who have successfully orchestrated change in our health care environment.”

Why should you attend QCOR Scientific Sessions?

Dr Madeline Sterling: There is a lot of programming geared towards early career professionals, which in my mind, makes QCOR really stand out as a ‘must attend’ conference for early investigators conducting cardiovascular outcomes research.

Dr Colleen McIlvennan: This year QCOR has six program tracks, including policy, health technology and innovation, implementation/QI/data science, cardiovascular clinical trialists forum, quality of care workshops, and Get with the Guidelines. New this year is a Design Thinking in Action workshop facilitated by Google.

Dr Tracy Wang: This year there will be a number of workshops with topics ranging from scientific publication, to advancing health care quality through collaborations with IT, to shared decision making. Plenary session topics will tackle two large and important areas for quality of care and outcomes research: the first will be on data science and health technology, the second will be on health policy and behavioral economics.

What are you looked forward to most at QCOR?

Dr Boback Ziaeian: I’m looking forward to people coming to my poster and seeing if they find the issue I report on as interesting. It’s something I’ve spent years thinking about and I’m curious how well I communicate my ideas.

Dr Ziaeian will be presenting his poster “Changes in the US Burden of Cardiovascular Mortality by Unique Weighting Methodologies” (Poster 294) at the afternoon poster session on Saturday April 6th.

Dr Madeline Sterling: Mike Thompson, PhD, Adam Bress, PharmD, MS, and I are leading the QCOR19 Career Development Luncheon. It will take place on April 5th at 12:30-2:00pm. The topic is ‘Building Bulletproof Collaborations.’ We’ve assembled some terrific panelists and table leaders to facilitate the discussion and I hope that many attendees will join for what I hope will be a dynamic and helpful session.

Dr Sterling will also be presenting her poster “Social Determinants of Health and 90 Day Mortality after Hospitalization for Heart Failure in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study” (Poster 284) at the afternoon poster session on Saturday April 6th.

How does QCOR focus on early career professionals?

Dr Madeline Sterling: Not only are there special abstract award presentations to highlight the top work of early investigators, but poster sessions, luncheons, and seminars with skill building exercises geared towards early career professionals. There are sessions with journal editors, as well as talks on mentoring and collaboration.

Dr Colleen McIlvennan: QCOR has always and continues to promote early career clinicians and investigators. A major focus of the conference is early career investigation with a highly coveted Young Investigator Award as well as oral abstract and moderated poster sessions. It’s a great council to join for those starting their career.

This year’s Young Investigator Award finalists are Enrico Giuseppe Ferro from the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Ali O Malik from Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Sameed Ahmed M Khatana from the University of Pennsylvania, Ashwin S Nathan from the University of Pennsylvania, and Tran Nguyen from George Washington Hospital in Washington DC. These 5 final abstracts will present in a special oral abstract session Friday morning (10:45 am) with the winner announced at the early career development luncheon to follow.

Dr Boback Ziaeian commented on how QCOR focuses on early career professionals throughout the year, not just at the annual scientific sessions. As a member of the QCOR Young Clinicians & Investigators Committee, he spoke to the significant amount of planning that occurs year-round for QCOR members.

“The council gives a voice to early career investigators by evaluating abstract submissions, developing content for conferences, and starting initiatives for the council community.”

Dr. Colleen McIlvennan, chair of the Young Clinicians & Investigator Committee, shared that the committee works “throughout the year on the programming for the early career events at QCOR’s annual meeting as well as early career programming at AHA Scientific Sessions.”

What’s a unique aspect of the QCOR Scientific Sessions?

Compared to other AHA conferences, the QCOR Scientific Sessions is relatively short (2 days) and small. But it’s a small conference with a big impact.

Dr. Colleen McIlvennan: Although QCOR is a relatively small conference by many standards, it really offers an impressive group of speakers and attendees. The size also allows for great networking opportunities!

Dr Madeline Sterling: It’s large enough where you can network and meet new people at each meeting, but small enough where you can also have quality time to catch up with colleagues and friends. Take me for example, a few years ago I went for the first time, not knowing a single person. I left 2 days later feeling inspired with new research ideas and a whole list of contacts.

Dr Tracy Wang: The early career lunches and panel discussion provide ample opportunity for members to network, reconnect, and learn from their peers; and I’ve taken advantage of the many nice little corners in our conference venue for 1-on-1 conversations and consultations.

Dr Boback Ziaeian: The conference is much more intimate and easier to navigate than some of the larger national conferences.

What session are you most excited about at QCOR Scientific Sessions?

Dr Madeline Sterling: I always love the Young Investigator Award finalists – it’s wonderful to see exciting work across the country from really talented young investigators. I’m also looking forward to the Get with the Guidelines sessions, clinical trial track, and health IT sessions.

Dr Boback Ziaeian: I think the Google session. But like most buzz-worthy scientific concepts, I expect a lot of hype.

Dr Colleen McIlvennan: The early career sessions are always a highlight. This year offers a great lineup: Young Investigator Awards (Friday at 10:45 am), Building Bulletproof Collaborations (Friday at 12:45 pm), Tell it to Me Straight: The Truth About Early Career (Saturday at 12:45 pm), and oral abstract and moderated poster sessions specifically for early career!

Dr Tracy Wang: Two novel collaborations will be featured this year. The Get with the Guidelines (GWTG) registries have been the flagship quality improvement program for the AHA, designed to promote guideline adherence, elevate quality of care, and improve patient outcomes across many cardiovascular diseases. While research from GWTG has historically had a strong presence at the QCOR conference, this year’s conference attendees will get to enjoy a deep dive into the what and how of organizing and implementing systems of care for outcomes improvement. (emphasis added) Also exciting this year is the collaboration between QCOR and the Cardiovascular Clinical Trialists Forum. Joint sessions will explore how real-world data can be leveraged for evidence generation, something that has been aspirational over the last decade but is now very firmly part of the clinical trial research landscape.

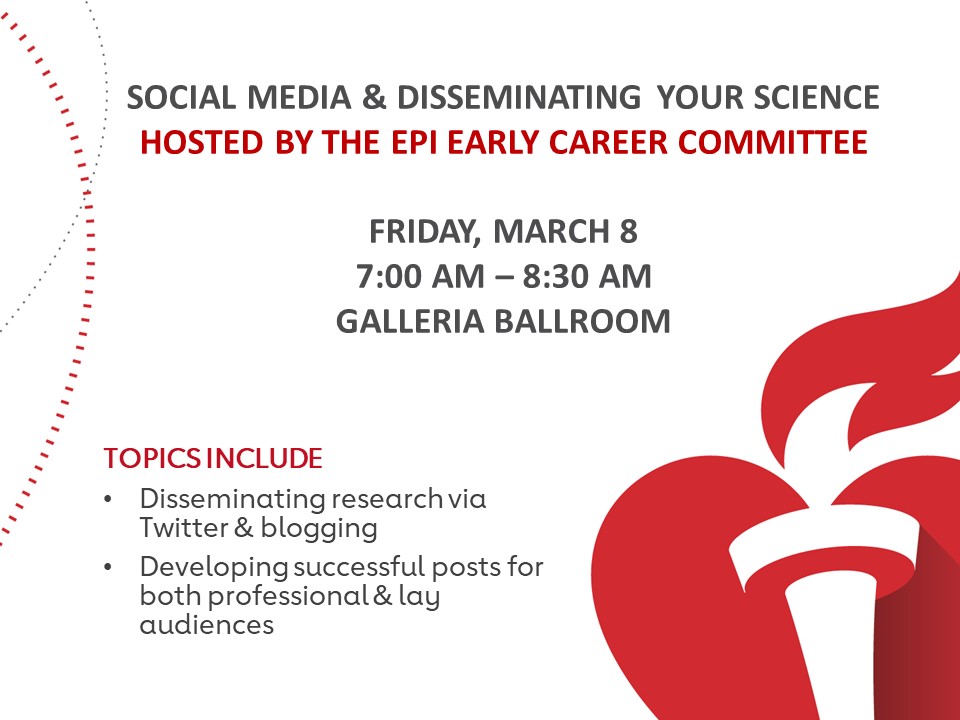

Want to follow along at #QCOR19?

You can follow #CQOMeetingReport and #QCOR19 as we live tweet from Arlington this weekend, as well as the Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes journal account (@CircOutcomes).

![Caption: A key Healthy People 2020 goal is to “create social and physical environments that promote good health for all”. You can learn more [here]. Image Source: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health](https://earlycareervoice.professional.heart.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2019/03/SDOH_fromHealthyPeople2020.png)

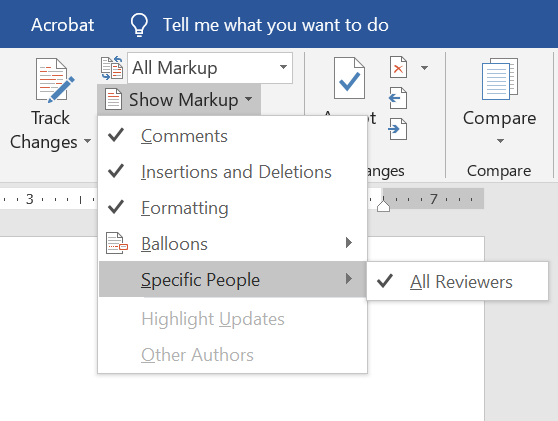

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

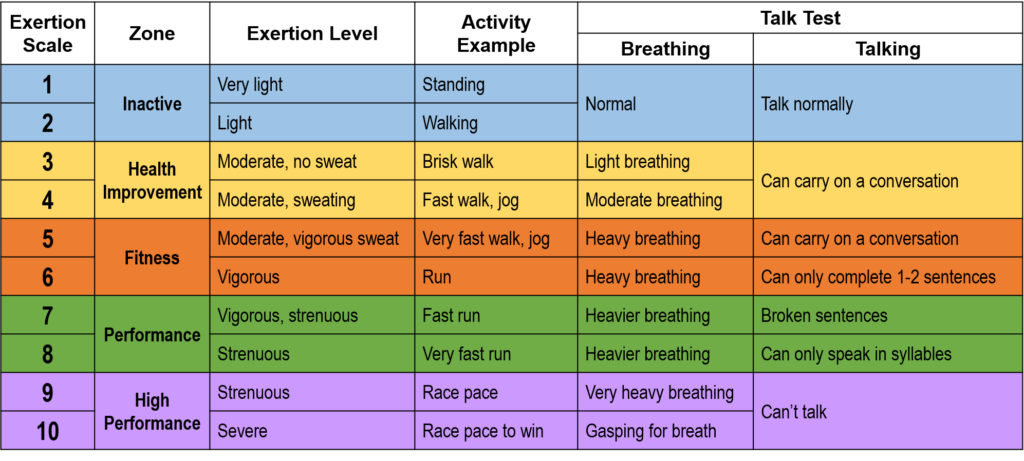

When I was a nutrition intern in 2014, I would excitedly tell patients that walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week doesn’t have to be a daunting goal. In fact, research showed that accumulating bouts of 10 minutes conferred cardiac benefits.

When I was a nutrition intern in 2014, I would excitedly tell patients that walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week doesn’t have to be a daunting goal. In fact, research showed that accumulating bouts of 10 minutes conferred cardiac benefits.