Collaborative Studies: Are They Worth It?

In a small evening session at the 51st annual Society for Epidemiologic Research meeting in Baltimore, MD, a group of epidemiologists from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health discussed the how and why of collaborative studies. Dr. Bryan Lau, Dr. Keri Althoff, Dr. Josef Coresh, Dr. Jessie Buckley, and Dr. Lisa Jacobson each presented on a key aspect of conducting successful collaborative studies, from getting investigators on board, to various data methods to address the inherent challenges of such heterogenous data.

Even after a long day of workshops, this session piqued my interest. The discussions – both candid and practical – addressed sides of collaborative science I had never thought of.

Note: This post will be 1 of 3 (or more!) on collaborative studies. Scroll to the end to see other topics I plan to address and leave a comment or Tweet us with feedback or questions.

Not All Collaborative Studies Are the Same

Let’s start with what we’re talking about when we say “collaborative study”. Dr. Lau presented this working definition: a collection of multiple independent studies collaborating together for a scientific goal.

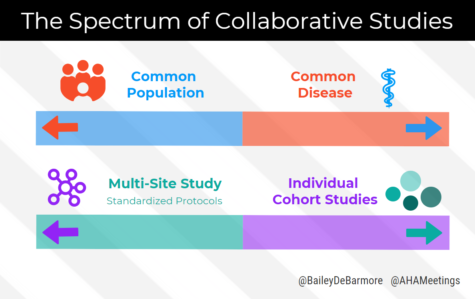

This broad definition groups together many different types of collaborative studies, from multi-site randomized trials with standardized protocols to pooled data from several different cohort studies. What these different examples have in common, however, is at least some overlapping data elements and buy-in from leaders of each participating study. I learned that these two ends of the collaborative science spectrum are often driven by common disease versus common population.

Common Disease

Studies of the same disease area typically have extensive overlap of data elements that are key in analyzing the condition. Dr. Lau gave the example of HIV, with the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration of Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), and CD4 count, viral load, and other measures almost always collected in HIV/AIDS research.

How could we apply that to cardiovascular and chronic disease research? It would be nearly unheard of to explore a heart disease question in a data set lacking medical history of diabetes, stroke, MI, hypertension; clinical measures such as total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and troponin in acute care questions.

Common Population

In contrast, if we want to examine childhood predictors of cardiovascular disease, we may combine different cohorts that start following participants at a young age. Unfortunately, these cohorts may be centered around different research questions – environmental exposures, asthma, developmental disorders – and may lack the research elements we want for cardiovascular risk, like basic lipid panels. Alternatively, some cohorts may have half of the data elements we want, but the other cohorts have the other half, and there’s nothing overlapping between them. How would we approach our analyses? We’ll talk about that in my post next month.

For now, let’s wrap up with a summary of the pros and cons of even conducting a collaborative study. With the picture I’ve painted so far, it seems like it can be frustrating, challenging, and perhaps not even doable.

Want to dig in more? Check out this paper “Collaborative, pooled and harmonized study designs for epidemiologic research: challenges and opportunities” published earlier this year in the International Journal of Epidemiology, by Drs. Catherine Lesko, Lisa Jacobson, Keri Althoff, Alison Abraham, Stephen Gange, Richard Moore, Sharada Modur, and Bryan Lau.

Why Should You Conduct a Collaborative Study?

The two main reasons we often put together collaborative studies is to increase sample size and try to increase generalizability.

Sample Size

Often a collaborative study can address research questions that aren’t answerable in the independent contributing studies – due to a lack of statistical power.

If you’re studying a rare outcome or exposure, or want to conduct subgroup analyses, you need numbers.

Generalizability

With increased sample size, you might think we have a better chance at generalizability. That’s a common misconception too large to address today, but you’re line of thinking isn’t completely wrong.

By combining different study populations, we’re getting closer to emulating a target population (if that is your target population), and that is why we have the potential for increased generalizability.

Note that I said potential – this segues into our discussion of the cons (or as I like to call them, challenges to overcome) in conducting collaborative studies.

Bigger Not Always Better

Increased sample size does not guarantee generalizability, as I outlined above. Similarly, all of that data coming in from each individual study may be subpar in data quality, and then you can’t combine it for your rare disease analysis or subgroup analyses. What will you do then? (Hint: in the next post on analyses strategies for collaborative studies, we’ll talk about how to optimize your meta data methods).

What else? Like I mentioned before, you may have all of your data elements measured in your contributing studies, but with no overlap. That can lead to unbalanced confounders. Let’s say all of your clinically measured hypertension variables are from two large studies out of the ten you’re combining. Are those two studies representative of the others? A similar issue is overall data harmonization, which can be thought of as a form of complete case analysis. Do you conduct your analyses with the lowest common denominator data elements – those that all studies have in common? We’ll talk more about meta data visualization and individual pooled analyses in the next post.

Logistics

How do you get buy-in from each study? Can you imagine the egos and the bureaucracy? Dr. Joe Coresh had some great advice from his work with Morgan Grams and the CK-EPID collaboration on how to smooth over logistical issues, from data use agreements, computational infrastructure, and transparency in procedures. Dr Lisa Jacobson had great advice, too – how to involve everyone in analyses, give primary authorship to contributing study investigators, and other tips and tricks for a successful collaboration. We’ll talk about that in post 3 of 3. Looking forward to it – hope you are!

Upcoming Posts:

- Analytical strategies for harmonizing data in collaborative studies

- How to conduct a successful collaborative study: the nitty gritty

- Interested in something else specific? Leave a comment or tweet us @BaileyDeBarmore and @AHAMeetings to let us know!

Follow Drs. Althoff and Lau on Twitter for great EPI methods tweets

- Keri Althoff – @KeriNAlthoff

- Bryan Lau – @BL4PublicHealth

Bailey DeBarmore is a cardiovascular epidemiology PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on diabetes, stroke, and heart failure. She tweets @BaileyDeBarmore and blogs at baileydebarmore.com. Find her on LinkedIn and Facebook.

Dr. Emelia Benjamin utilizes the theories from Kathy Kram, Monica Higgins, and David Thomas on “Creating Developmental Networks” and “Reconceptualizing Mentoring” with her early career faculty at BU. Take a cue from her, and use this worksheet,

Dr. Emelia Benjamin utilizes the theories from Kathy Kram, Monica Higgins, and David Thomas on “Creating Developmental Networks” and “Reconceptualizing Mentoring” with her early career faculty at BU. Take a cue from her, and use this worksheet,