Key Takeaways From the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure

What’s new in the treatment of heart failure? The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management was just released in the beginning of April! While much of the ground it covers might not seem particularly groundbreaking to anyone who has been paying attention to discussions on #MedTwitter, #CardioTwitter or the latest clinical trials over the last 2-3 years, it codifies the guideline directed medical therapy (GDMT) that we have all come to know and love for the treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). These new guidelines also provide the first-ever guideline recommendations for patients with (heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction) HFpEF and heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), though the strength of recommendation for these conditions is not as strong as those for HFrEF.

Here are some key takeaways from the new heart failure guideline!

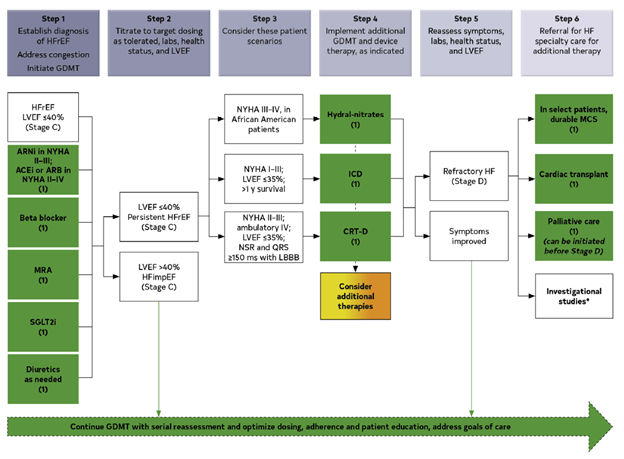

- Quadruple therapy GDMT for HFrEF

The latest guideline officially provides class IA recommendations for the use of the following medications in the treatment of HFrEF (defined as LVEF 40% or lower) in patients that have at least NYHA class II symptoms:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (ACEi) [i.e. lisinopril] or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) [i.e. losartan] or angiotensin receptor blocker/neprolysin inhibitor combination (ARNi) [i.e. sacubitril-valsartan]

- Beta blockers [i.e. metoprolol, carvedilol]

- Mineralocorticoid antagonists [i.e. spironolactone]

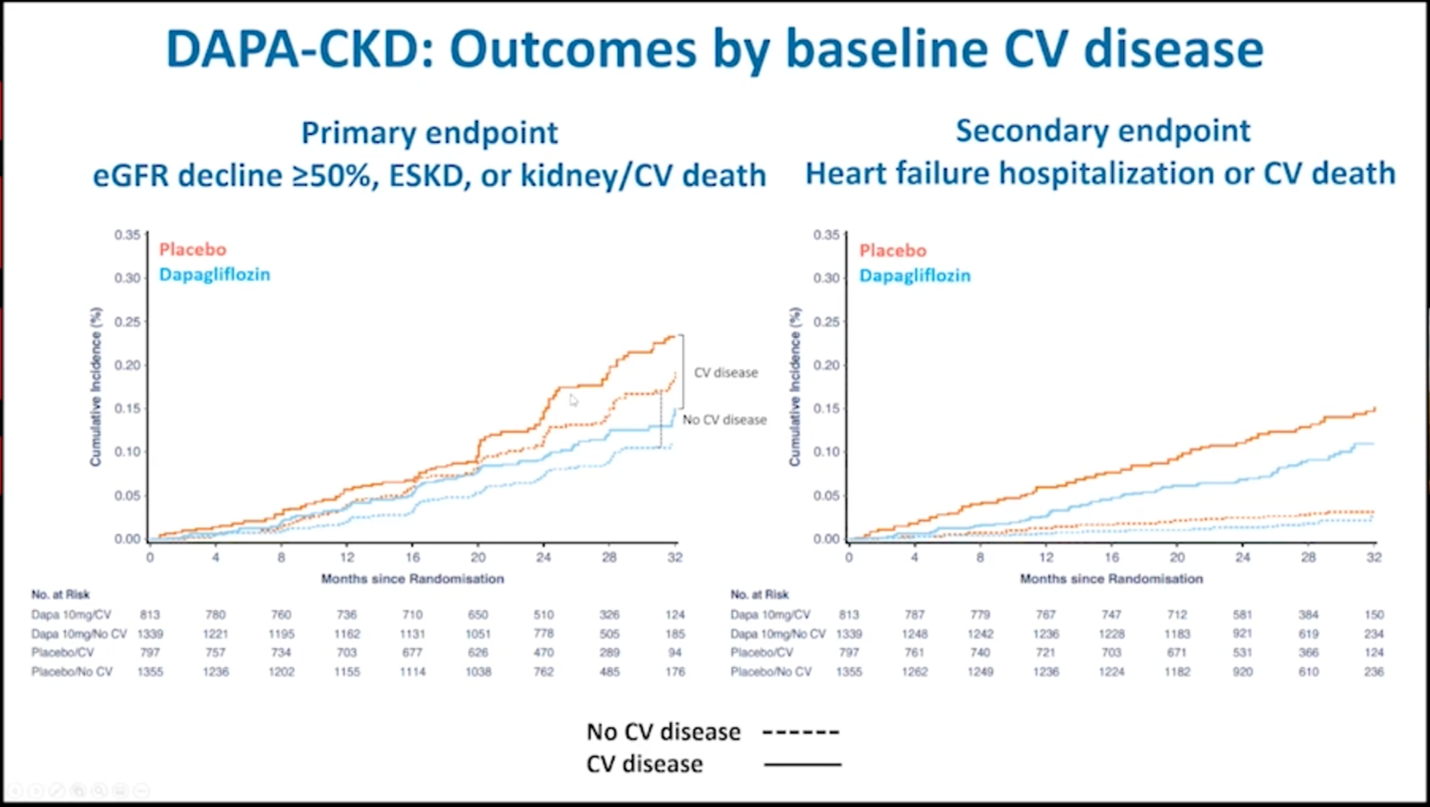

- SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLTi) [i.e. empagliflozin, dapagliflozin]

The first three classes were previously recommended for the treatment of HFrEF but prior American cardiovascular society guidelines did not include such a strong recommendation for the use of SGLT inhibitors.

- We now have HFimpEF

HFimpEF now refers to heart failure in someone who previously had HFrEF but whose LVEF has improved to >40%. The guideline strongly recommends continuing GDMT for patients that fall into this category.

- We now have HFmrEF recommendations

The guideline now provides a class 2A recommendation for the use of SGLT2i in the treatment of symptomatic HFmrEF (defined as LVEF 41-49%). It also provides class 2B recommendations for the use of ARNi/ACEi/ARB, beta blockers and MRAs in these patients. These recommendations confirm what some physicians/cardiologists have already begun doing in practice, though the level of evidence to support the use of these medications in HFmrEF as it is for patients with HFrEF.

- We also have new HFpEF recommendations

For the first time ever, the guideline recommends medications for the treatment of symptomatic HFpEF (defined as LVEF 50% or greater). Similar to its recommendations for the treatment of HFmrEF, it provides a class IIA recommendation for the use of SGLT2i and class 2B recommendations for beta blockers, ARNi, ACEi, ARB and MRAs, especially if the patient has an LVEF that is closer to 50%. Again, as we know, the level of evidence to support these practices is not as strong as it is for HFrEF. Still, this represents a change from previous guidelines which provided limited options for treatment of HFpEF.

- ICD or CRT is still recommended for primary prevention in certain cases

This guideline continues to recommend an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in a subset of patients, particularly those whose LVEF remains less than or equal to 35% despite being on maximally-tolerated GDMT (there are nuances to this that we will not get into here). Similarly, as before, the guideline also continues to recommend cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) for patients who have an LVEF less than or equal to 35%, sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block with a QRS duration of at least 150 ms, NYHA class II-III symptoms.

- New recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis

The new guideline provides class I recommendations for checking serum and urine immunofixation electrophoresis and serum free light chains in patients (which would help diagnose AL amyloidosis) in patients for whom there is clinical suspicion for cardiac amyloidosis. Similarly, there is a class I recommendation for bone scintigraphy to evaluate for transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis in patients for whom there is sufficient clinical suspicion for amyloidosis (left to the clinician’s judgment). Genetic testing is also recommended if a patient is diagnosed with TTR amyloidosis. For the first time, the guideline provides a class IB recommendation for the use of tafamadis in patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. And finally, the guideline gives a class IIA recommendation for use of anticoagulation in patients with concurrent atrial fibrillation and cardiac amyloidosis, regardless of CHA2DS2-VASc score.

“The views, opinions, and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness, and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke, or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

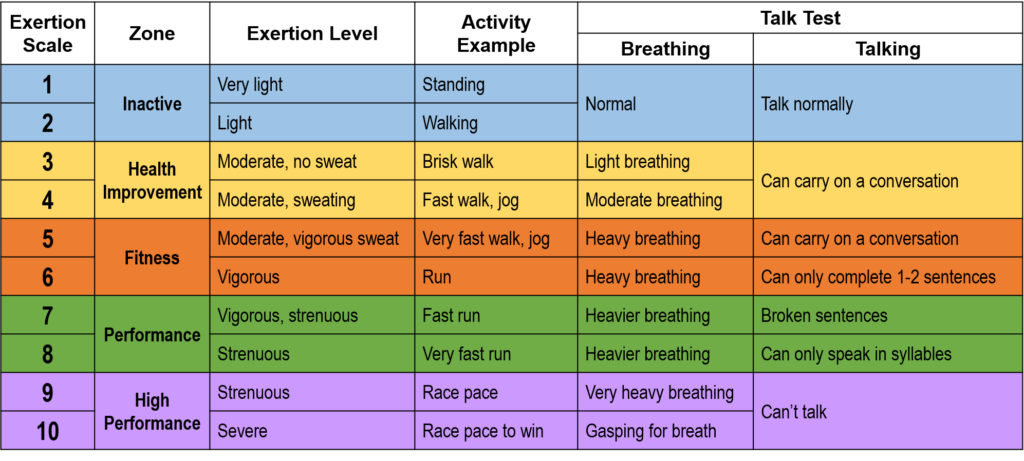

When I was a nutrition intern in 2014, I would excitedly tell patients that walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week doesn’t have to be a daunting goal. In fact, research showed that accumulating bouts of 10 minutes conferred cardiac benefits.

When I was a nutrition intern in 2014, I would excitedly tell patients that walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week doesn’t have to be a daunting goal. In fact, research showed that accumulating bouts of 10 minutes conferred cardiac benefits.