3 Tips for Incorporating Coauthor Feedback

When we review a paper, we often forget how we feel in the role of author. Along the same lines, when we read over drafts coauthors’ send us, we forget how we act in the role of editor.

Suggested changes seem personal.

Tip #1: Get your head right

We often have coauthors at different institutions and finalize manuscripts via email. Receiving criticism, constructive or otherwise, is never pleasant but receiving criticism over email opens the situation up to miscommunication.

Why?

When we write or read an email, our current mood influences how we perceive it.

Incorporating coauthor feedback is a key step in the science writing process, and seeing it as an integral part of the final product and not a burden to be borne can help you orient yourself. Approach the process constructively and with an open mind.

“You cannot grow if you are not willing to change, to accept new perspectives on life or to change your habits.” – Steven Aitchison

Tip #2: Consider the type of feedback

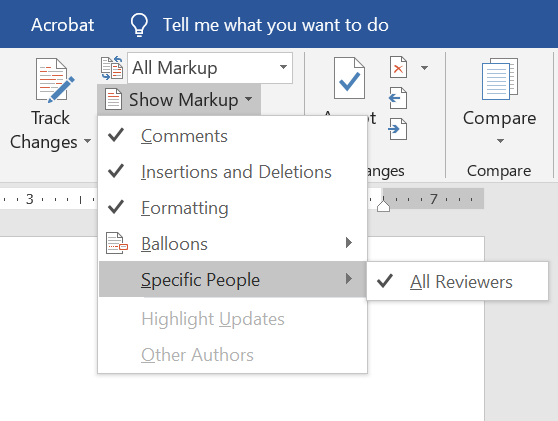

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

and then “Specific People”.

As you read through feedback, I’d like you to think about them as 4 types of feedback.

- Clarifying content

- Modifying style elements

- Correcting grammar

- Changing wording

Simplifying wording often leads to clarifying content. Modifying style elements, such as use of “First,…” “Second,…”, “…; however…”, or by changing passive to active voice, often modify writing style but may also increase or decrease writing clarity.

Kristin Sainini teaches the online Coursera course “Writing in the Sciences” and uses assignments like “Give a short word that means the same thing as “utilize””. Here’s a table of words that can be simplified.

| Instead of… | Use… |

| Accordingly, | So |

| Address | Discuss |

| Afford the opportunity | Allow |

| Advantageous | Helpful |

| Due to the fact that | Due to, since |

| Determine | Decide, figure, find |

| Demonstrate | Show |

| Evident | Clear |

| Evidenced | Showed |

| In lieu of | Instead |

| In regard to | About, concerning |

| Magnitude | Size |

| Notwithstanding | In spite of, still |

| Numerous | Many |

| Preclude | Prevent |

| Provided that | If |

| Provides guidance for | Guides |

| Represents | Is |

| Similar to | Like |

| Subsequent | Next |

| Subsequently | Then |

| Sufficient | Enough |

| Therefore | So |

| Utilize | Use |

| Viable | Practical |

| Warrant | Call for |

CAPTION: Not all of them involve fewer words. Some are just more common in spoken language, and so better understood. [Source]

Correcting grammar is often straight forward, but may be stylistic. Double check with a style guide or online grammar guru like Grammarly. If you’re both right, feel free to keep your own. Consistency throughout the manuscript – both in writing style and grammar choices – is important.

If they are suggesting a change in wording, think about why. Is it a simpler word? Is it more correct?

If you write with the same coauthors frequently, you may find certain people predominantly provide a certain type of feedback.

Then, think about the purpose of an edit. Why do you think the coauthor made that suggestion?

If the suggestion is a stylistic change that doesn’t clarify content or simplify wording, then it’s an edit that shifts your writing style towards their own. These are edits that, in my opinion, you are not “required” to make. But if you know your writing could benefit from some streamlining, look at what these edits are. Are they moving the main subject from the end to the beginning of the sentence? Adding transitions? Cutting out unnecessary words? These are changes you can make in your own writing style to improve communication.

However, keep in mind when you are providing feedback on someone else’s writing that these comments aren’t always helpful. Instead of trying to mold someone’s words into your own, assess writing for clarity and purpose.

If a coauthor changes a word that changes the meaning of a sentence – that’s a big problem. Definitely don’t change anything that results in a false statement, but acknowledge that if someone on the project didn’t understand what you were trying to say, a reader definitely won’t. That sentence needs to be clarified. Spend time on these edits to make sure what you’re trying to say is coming across.

Tip #3: Stand up for yourself

Hopefully you have a great group of mentors, and at least one is in your coauthor group.

Don’t hesitate to have a frank conversation with your mentor about manuscript editing. They have much more experience than you, and have encountered many different frustrating situations. Some of the best advice I’ve gotten is to “choose your battles”. Not only does that mean to let some things go, but think about what you’d like to stand up for.

Being able to edit someone’s writing without replacing their writing style is difficult. Not all coauthors, no matter how senior, are able to do so.

Recently, a colleague in my lab group asked for advice on how to handle conflicting coauthor feedback. My mentor brought up a good point: many times, in academia we don’t feel like we are “doing our job” if we don’t come up with a suggestion. As the “commenter”, we feel satisfied with ourselves for contributing. But as the recipient, we consider all feedback and suggestions as changes to make.

Having straight forward discussions about what changes benefit the paper as a whole not only improve your communication skills, but your independence.

What challenges have you encountered in this area?