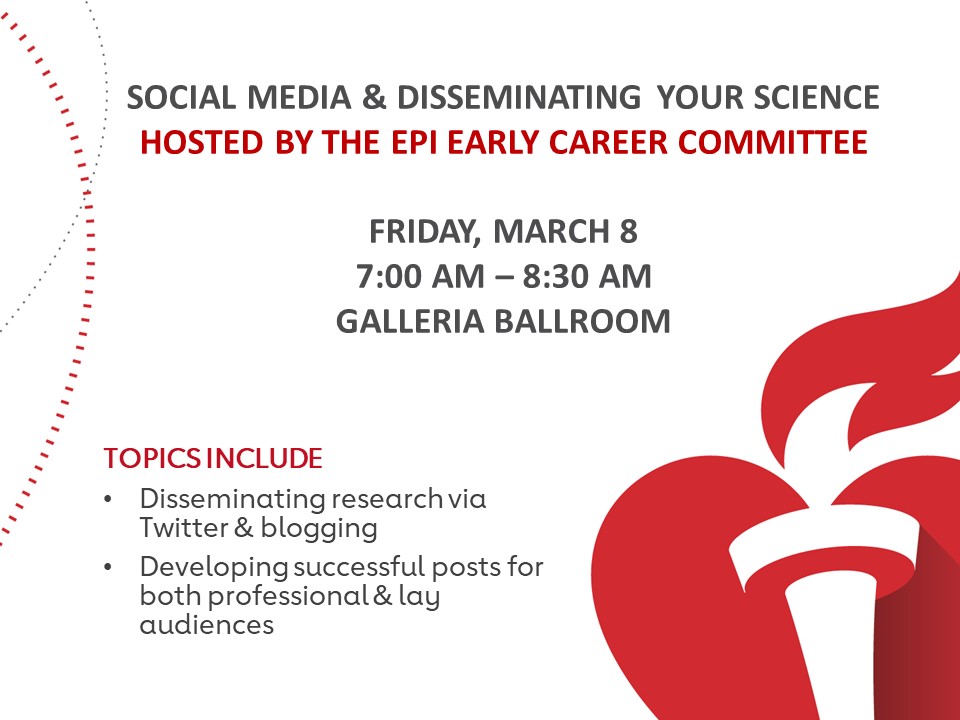

The AHA Epidemiology and Prevention and Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health Scientific Sessions is quite different from AHA Scientific Sessions. Smaller in size and more focused, with few concurrent sessions and ample coffee breaks, I enjoyed attending the numerous Early Career sessions. They varied in topic and format: “Connection Corners” were short round-table discussions twice a day with focused conversations on ‘beefing up your CV’, the grant writing process, developing a catchy elevator speech, and leveraging non-NIH funding. Both the EPI-Prevention and Lifestyle councils had lunchtime panels at the end of their annual business lunches, and had the audience asking questions about avoiding burnout in academia and global collaboration in cardiovascular research.

To end the week, the Early Career Council outdid themselves with the early morning ‘fire-side’ chat with Drs. Emelia Benjamin, MD ScM from Boston University School of Medicine, Norrina Allen, PhD from Northwestern Medicine, Jean-Pierre Després, PhD from Laval University in Quebec, Chiadi Ndumele, MD MHS from Johns Hopkins Medicine, and Lenny Lopez, MD MDiv MPH from UC San Francisco.

Drs. Emelia Benjamin, Jean-Pierre Depres, Chiadi Ndumele, Lenny Lopez, and Norrina Allen (left to right) provide eye-opening mentoring advice to early career investigators at the EPI Lifestyles Scientific Sessions 2018 in New Orleans, LA.

If you missed this morning session, no worries! I have you covered. The panel conversation, led by Dr. Emelia Benjamin, started with finding your niche as an early career investigator, and developed into a great discussion on building a mentoring team and planning your own path.

Using Sli.do to anonymously ask questions allowed for an unbiased view of what the audience was thinking. And overwhelmingly were questions along the lines of:

- What do you do if your mentor selects a niche for you that doesn’t excite you?

- How do you separate your niche from your mentor?

- What can you do to fix a fall-out with your mentor?

I found these questions concerning! To me, they reflect a mentee perspective that 1) once you’re assigned a mentor, you’re stuck with them; 2) your mentor is the be-all-end-all guide in your career path; and 3) you must do everything your mentor tells you.

My first response to this perspective is: we’ve got to shift this mindset! If your relationship with your mentor is that of a duckling and mother goose, something has got to change. A mentor that “assigns” a research niche to you is either a Tormentor or is responding to your lack of initiative. If the former, you should find a new mentor. Your institution will have a number of resources including a faculty affairs office or an ombudsman and possibly a mentoring program that will help you find a mentor that best fits with your needs.

If the latter, you’ve got some work to do! But the career panel provided some great advice on how to get started. (So do Vineet Chopra, MD MSc, Vineet M. Arora, MD MAPP, and Sanjay Saint, MD MPH in an article titled “Will you be my mentor?” published in JAMA last year).

Make the most of your time

Mentors have a number of responsibilities and how they have made their own career path and achieve work life balance is a great indicator if you will be a good fit. Do you aspire to a career like theirs? Do you admire their work-life balance? They might make a great life or career mentor for you.

Just as you expect your mentor to give you their full attention when discussing your goals, you must respect their time as well! That means giving thought to your research goals, planning the steps to get there, and using their expertise and experience to provide direction and improve your process.

Set up a meeting with your mentor and prepare an agenda beforehand. Know the topics you’d like to cover, whether their input on goals and milestones, plans for research projects, or ideas to brainstorm on. Preparing an agenda shows respect for both of your times and keeps you on track for a productive meeting. Jot down action items and follow-up after the meeting.

Judy T. Zerzan, MD MPH and coauthors discuss “managing up” and how to take responsibility for your half of the mentor-mentee relationship in “Making the Most of Mentors: A Guide for Mentees.”

Earlier this year, Dr. David Werho wrote about sponsorship versus mentoring in his 2-part article “When Mentoring Isn’t Enough”. Read Part 1 and Part 2 to learn about why dependability pays off, how to diversify and be the protégé you want, and why it’s worth it to do your homework.’

One is the Loneliest Number

Another solution to mentor woes is creating a mentor network. Over and over, the panel expounded on the advantages of having both a primary mentor and a mentoring group. This structure is explicit in career development grants, where the primary mentor supports your career development initiatives, and the content and methods experts support your training goals. Content and methods mentors in your network can also help you explore different areas in your field as you work to identify your research niche.

A mentor network means different researchers with different backgrounds and different perspectives. Bouncing your research ideas off them results in contrasting views, some that will jive more with you, and some that will make you think. Instead of being molded into a “mini”-me mentee, a mentor network helps you build the scaffolding upon which you’ll grow into your own independent researcher.

I’ll touch more on this idea later, but here’s a great read from Yan Shen, Richard D. Cotton, and Kathy Kram for the MIT Sloan Management Review. Even if you are post-tenure, you still benefit from a strong mentoring network! Read more from Kerry Ann Rockquemore in “Posttenure Mentoring Networks.”

Identifying a Niche

The pre-established theme of the Friday morning early career session was how to “Identify Your Niche”. While much of the discussion centered around mentoring and its supportive role in finding your niche, there was also focused advice on how to find your way.

The panel emphasized that as an early career investigator, it’s imperative to utilize this time to identify and achieve the additional training you see as important to your overall career goals. While this may be in the form of a post-doctoral position or a K-award, it can also be informal in the research projects you pursue and the skills you acquire.

Dr. Emelia Benjamin, who provides mentoring support to early career faculty at Boston University, gave us 2 homework assignments to help us plan our way.

First, reflect on where you’ve been and where you’re going. A 1-page personal statement makes a powerful addition to your CV, and the journey to this final product will help you learn to tell your story as a connected arc, rather than a zig-zag path jumping from topic to topic. The evolution of your research niche from project to project is hardly evident in your publication list, but through narration and self-reflection you can illustrate your approach to the scientific process and summarize where you might go next. Not only will you provide a picture of your research goals and personality to anyone reading your CV, but you will likely have a few “Aha!” moments discovering connections between projects you hadn’t seen before.

Second, diagram your mentoring network. It’s important to visualize this – are all of your mentors above you? Below you? Horizontal to you? Peers? Are they in the same division, institution, or all distance? A mixture is key, but the components of that mixture depends on your research and career goals. Dr. Chiadi Ndumele from Johns Hopkins Medicine shared his take on 5 valuable types of mentors to have:

- Methodological mentors are those you go to for questions and feedback about approach.

- Content or clinical mentors are those you go to about patient care of content expertise.

- Life mentors are those whose work-life balance is one you admire.

- Career mentors help you step back and see the big picture, particularly the asks you should say no to.

- A brainstorm mentor plays devils advocate and is a great sounding board to bounce ideas off of that also bounces back.

Dr. Emelia Benjamin utilizes the theories from Kathy Kram, Monica Higgins, and David Thomas on “Creating Developmental Networks” and “Reconceptualizing Mentoring” with her early career faculty at BU. Take a cue from her, and use this worksheet, Define your Developmental Network, to identify the gaps in your mentoring network, and take the first step to filling them.

Dr. Emelia Benjamin utilizes the theories from Kathy Kram, Monica Higgins, and David Thomas on “Creating Developmental Networks” and “Reconceptualizing Mentoring” with her early career faculty at BU. Take a cue from her, and use this worksheet, Define your Developmental Network, to identify the gaps in your mentoring network, and take the first step to filling them.

Bailey DeBarmore is a cardiovascular epidemiology PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on diabetes, stroke, and heart failure. She tweets @BaileyDeBarmore and blogs at baileydebarmore.com. Find her on LinkedIn and Facebook.

![Caption: A key Healthy People 2020 goal is to “create social and physical environments that promote good health for all”. You can learn more [here]. Image Source: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health](https://earlycareervoice.professional.heart.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2019/03/SDOH_fromHealthyPeople2020.png)

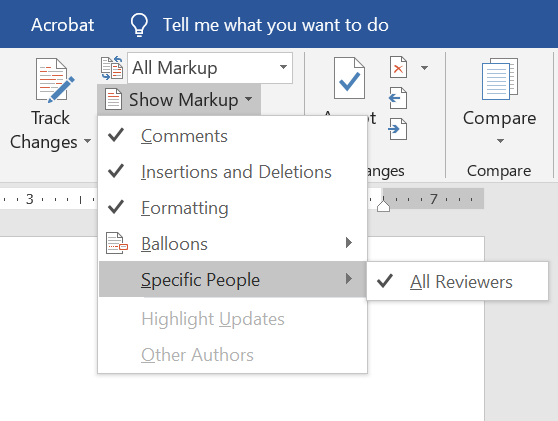

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

Dr. Emelia Benjamin utilizes the theories from Kathy Kram, Monica Higgins, and David Thomas on “Creating Developmental Networks” and “Reconceptualizing Mentoring” with her early career faculty at BU. Take a cue from her, and use this worksheet,

Dr. Emelia Benjamin utilizes the theories from Kathy Kram, Monica Higgins, and David Thomas on “Creating Developmental Networks” and “Reconceptualizing Mentoring” with her early career faculty at BU. Take a cue from her, and use this worksheet,