25 Useful Tips for Establishing a Writing Routine

I am a notorious writing procrastinator. As a graduate student, I consistently used stress and the doom of pending deadlines to drive my writing practices. While I rarely missed deadlines, this writing process was exhausting and often left me reluctant to initiate new writing tasks. Determined to break the cycle, I began integrating a writing routine into my schedule as a postdoc. At its core, a writing routine is a commitment, a promise to adhere to regular writing habits to more effectively tackle large writing tasks. However, a writing routine can be so much more than a tool. By carving out time and a sacred space in which to write, these practices can bring back joy to the task of writing. Don’t get me wrong. It’s not easy. Developing a solid writing routine requires commitment, practice, and revision (as you identify and modify what works for you). After six years of working with a writing routine, I am still far from perfect and stray all the time from good practices, especially when a deadline appears deceptively distant. However, writing routines have changed my feelings about writing and I would encourage everyone to give them a try. I recently ran a Writing Routine Workshop where I asked the class about their strategies for maximizing their writing productivity. So, if you are starting a writing routine or looking for ways to improve the routine you have, here are 25 new ideas to try out.

- Define your writing time. Determine what time is best for you and block off this time on your calendar. Some people write best in the morning after a cup of coffee. Other people write best in the evening when life is a bit quieter.

- Establish a writing area. Set yourself up for writing success by creating an environment that allows you to write productively.

- Identify and eradicate distractions. Major distractions include cell phones and the internet. Among workshop participants, techniques to minimize distractions varied widely. Among the methods shared: put down your cell phone, turn off your cell phone, and close all of the windows in your internet browser. One individual even said they turn off their WiFi router to avoid distractions — yikes.

- Pick out some good tunes or move to a quiet space. Some people require absolute silence, while others write best while listening to music. Figure out what helps you get in the zone and incorporate this into your routine.

- When you are stuck, go for a walk. Sometimes getting up and moving around can help you develop new ideas or break up long writing sessions.

- Exercise. For many people, exercise and writing go hand in hand. Some people come up with their best ideas while jogging. Try it out!

- Treat yourself! After you write a substantial amount text or for a considerable amount of time, reward yourself with a snack, a drink, or some time on the internet.

- Gamify your writing. Keep track of how many words you write each day and try to write as much or more each subsequent day.

- Use productivity apps or the Pomodoro Technique to stay focused for short writing bursts.

- Non-science writing before science writing. “Warm-up” first by writing about non-science topics before writing about science.

- Read to inspire. Read an inspiring paper or grant before writing.

- Write now, edit later. Write freely and then edit later.

- Form a writing pact with friends. Start a writing routine with a friend, then hold each other accountable.

- Write with others. Similarly, you can form a writing team. Commit to a time and place (even over Zoom works) to write together. Encourage each other to stay the course.

- Force yourself to write by creating artificial deadlines. Promise to send a draft to a friend or mentor and adhere to this promise.

- Quiet that inner negative voice. Don’t get discouraged and toss out what you just wrote after you write. First, acknowledge that you are writing the first draft and that it won’t be perfect from the very beginning. Second, figure out what you don’t like about what you wrote and work to make it better. Third, seek feedback from others if you cannot figure out what you don’t like about what you wrote because sometimes you need an outside perspective.

- Coffee or tea. Caffeine is sometimes the stimulant people need to get started. The ritual of preparing a cup of coffee or tea can also function as a trigger to begin the writing process.

- Break it down. Break up your large (seemingly impossible) writing task into smaller accomplishable pieces. Then create a schedule to space out deadlines and help you finish the writing task.

- Build writing bridges. At the end of your writing time, note down what you want to write next. A writing bridge will help you start writing again and excite you to continue.

- Just sit there and write. Commit to your writing time. Even if you are stuck, make yourself sit there and write. If you are having an uninspired writing day, start by with an easier writing task like the materials and methods (for a paper) or the personal statement (for a grant).

- Get out of the lab. On par with avoiding distractions, sometimes it’s just best to write in a space with fewer distractions.

- Snack writing. Acknowledge that you cannot set aside large swaths of time for writing and begin writing in small snack-like pieces. Write while eating lunch. Write down notes while waiting for a spin or a reaction to occur.

- Outline it! If you don’t know where to start, begin with a rough outline and gradually expand on areas until you have a coherent first draft.

- Awake writing vs. sleepy writing. There are times when we are all tired and unable to write our best. On these days, focus on more manageable writing tasks like preparing outlines or writing documents that require less mental energy like figure legends or the equipment document of your NIH grant.

- Adapt your writing routine as needed. On average, it takes about 66 days for a daily practice to become a habit. Be kind and honest to yourself. If your writing routine is not working for you, adjust it to fit your needs. Most importantly, try to stick with it.

Additional resources

1. Peterson TC, Kleppner SR, Botham CM (2018). Ten simple rules for scientists: Improving your writing productivity. PLoS Computational Biology 14(10): e1006379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006379

2. Gardiner M and Kearns H (2011). Turbocharging your writing today. Nature 475: 129-130. doi:10.1038/nj7354-129a

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

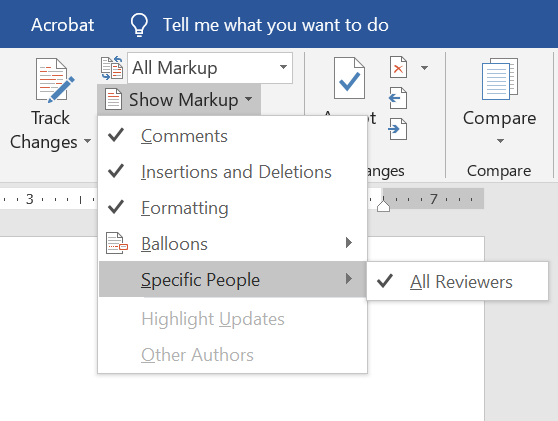

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,