American Heart Association and California Walnut Commission Joint Initiative to Support Walnut Research

Picture from https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/go-nuts-but-just-a-little

Earlier this year, The American Heart Association and the California Walnut Commission (CWC), a non-profit organization funded by mandatory assessments of the growers, announced a special award to support early career scientists pursuing human clinical or epidemiological research on walnut consumption.1 This presents an exciting opportunity to engage early scientists interested in improving public health outcomes through walnut research. This initiative with the American Heart Association opens new opportunities to increase our scientific knowledge of the benefits of walnut consumption in heart and brain health. With the ongoing efforts to pursuit a healthy lifestyles through a healthy diet, we find ourselves with nuts being inclusive in the many diet options we see these days.2-3

Walnuts provide 190 calories per one-ounce serving, which is equivalent to 1/4 cup, which is equivalent to approximately 12-14 walnut halves or a handful. They are also a good-fat food with 13 grams of polyunsaturated and 2.5 grams of monounsaturated fat of the 18 grams of total fat in one ounce of walnuts. Other benefits include its 2 grams of fiber per one ounce serving, important for heart health, gut health, and weight management. Walnuts are a rich source of Vitamin B6, Magnesium, Melatonin, Copper, and Manganese.4 The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends the consumption of unsaturated fats over saturated fats, thus supporting the consumption of nuts, and walnuts.5 These further present a healthy option as a non-animal source of proteins. The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association document on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular disease risk supported its inclusion due to cardiovascular benefits associated with walnut consumption in the studies.6 Given the ongoing burden from heart attacks and strokes, we will continue to see a shift towards optimization of dietary patterns as modifiable risk factors in the prevention of cardiovascular disease.

There are many benefits from the consumption of walnuts. There is an increasing body of knowledge as a result of the studies targeting health outcomes. Study findings suggest benefits in diastolic function in young to middle-aged adults. 7 Based on results from prospective cohort studies, the consumption of peanuts and tree nuts (2 or more times/week) and walnuts (1 or more times/week) has been associated with a 13% to 19% lower risk of total cardiovascular disease and 15% to 23% lower risk of coronary heart disease.8 Most recent studies suggest that walnut consumption may benefit cognitive performance and lead to improvement in memory in adults.9 Other studies report maintenance of weight loss and self-reported satiety.10

Despite these research findings, additional studies are needed to further advance our understanding of the complexity of plant protein vs. animal protein comparisons.11 While many epidemiologic and intervention studies have evaluated their respective health benefits, it has been difficult to isolate the role of plant or animal protein on cardiovascular disease risk. The potential mechanisms responsible for specific plant and animal protein effects are multifaceted.11 Further investigations should test the effects of long-term consumption of nuts on cardiometabolic events.

A better understanding of its benefits may also contribute to higher consumption of walnuts. Especially when Americans do not meet the recommendations in the consumption of seafood, nuts, seeds, and soy products.5 Nuts have been shunned away for many years due to the perception as high-fat foods and promoters of weight gain. Work remains to be done to change this perception of weight gain associated with nuts, and walnuts.

The initiative as a result of joint efforts between the American Heart Association and the California Walnut Commission will provide the booster needed to support research and science on walnuts. A better understanding of its mechanism of action, benefits, and people’s perceptions of nuts, and walnuts perhaps may contribute to their increased consumption for heart and brain health, among other outcomes.

Applications open in October, for more information visit: https://professional.heart.org/en/research-programs/application-information/career-development-award

References:

1.American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). California Walnuts and American Heart Association announce first joint funding award. EurekAlert! https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/589498. Jan 5, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2021.

- Uusitupa M, Khan TA, Viguiliouk E, et al. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes by Lifestyle Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2611. Published 2019 Nov 1. doi:10.3390/nu11112611

- Chiavaroli L, Viguiliouk E, Nishi SK, et al. DASH Dietary Pattern and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):338. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.3390/nu11020338

- California Walnut Commission. Walnuts Support Overall Wellness. https://walnuts.org/wp-content /uploads/2021/07/P0274-NutritionFactsHandout_8.5×11-1.pdf. 2021. Accessed August 15, 2021

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

- Ros E. Eat Nuts, Live Longer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(20):2533-2535. doi:10.1016/ j.jacc. 2017. 09.1082

- Steffen LM, Yi SY, Duprez D, Zhou X, Shikany JM, Jacobs DR Jr. Walnut consumption and cardiac phenotypes: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31(1):95-101. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2020.09.001

- Guasch-Ferré M, Liu X, Malik VS, et al. Nut Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(20):2519-2532. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.035

- Chauhan A, Chauhan V. Beneficial Effects of Walnuts on Cognition and Brain Health. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):550. Published 2020 Feb 20. doi:10.3390/nu12020550

- Rock CL, Flatt SW, Barkai HS, Pakiz B, Heath DD. Walnut consumption in a weight reduction intervention: effects on body weight, biological measures, blood pressure and satiety. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):76. Published 2017 Dec 4. doi:10.1186/s12937-017-0304-z

- Richter CK, Skulas-Ray AC, Champagne CM, Kris-Etherton PM. Plant protein and animal proteins: do they differentially affect cardiovascular disease risk?. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(6):712-728. Published 2015 Nov 13. doi:10.3945/an.115.009654

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

Dr. Pearson’s own mentors reflected his insatiable curiosity. As a student, he drew from a broad mentoring team that left lifelong impressions of the qualities of good mentor. While excellent teaching was important, more so was the “utterly frank” assessment and advice they provided him. He states, “from them I learned that the primary role of a mentor is to provide an honest, encouraging perspective on the mentee’s ideas, plans and experiences. While some mentors may be tempted to acquiesce or tell mentees what they want to hear- that is abrogation of their responsibility of a mentor.” Such frankness can be tough in today’s academic environment, so to help cultivate this skill, Dr. Pearson’s University of Florida developed the

Dr. Pearson’s own mentors reflected his insatiable curiosity. As a student, he drew from a broad mentoring team that left lifelong impressions of the qualities of good mentor. While excellent teaching was important, more so was the “utterly frank” assessment and advice they provided him. He states, “from them I learned that the primary role of a mentor is to provide an honest, encouraging perspective on the mentee’s ideas, plans and experiences. While some mentors may be tempted to acquiesce or tell mentees what they want to hear- that is abrogation of their responsibility of a mentor.” Such frankness can be tough in today’s academic environment, so to help cultivate this skill, Dr. Pearson’s University of Florida developed the

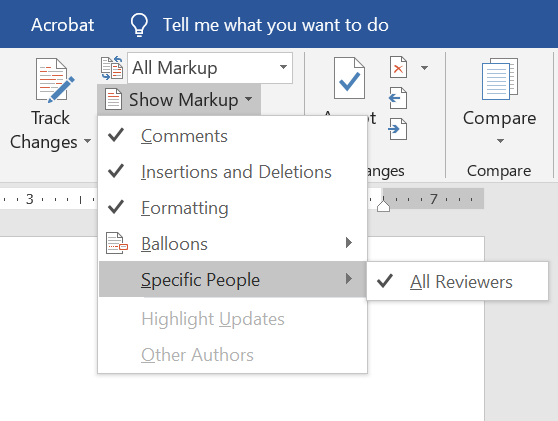

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,

So, you’ve taken a deep breath and opened up the document with coauthor feedback. Plan to make several sweeps through the document. If you have comments from several people in one document, consider isolating each author. If you’re using Microsoft Word, you can do this by going to the Review pane, selecting “Show Markup”,