Many of my fellow bloggers here at AHA Early Career Voice are clinicians, and we’re all busy, and we all see the value in research. I wanted this post to speak to everyone who feels they’re spinning the plates of patient care, research, personal life, and having something to show for it all (besides broken china). Figuring answers from someone who makes it look easy would be a good place to start, I shot my colleague, Stephen Juraschek, MD PhD, an email.

And you thought juggling was hard…

“Are you going to AHA EPI?”, I ask him on an afternoon phone call. “Yeah! Have you been to New Orleans before?” No, I reply. He hasn’t been either. We’re both excited to reconnect with colleagues in epidemiology and lifestyle prevention at the annual specialty conference held in March. This year it’s in New Orleans. Next year is Houston.

Connected by our time at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research, we talk about what distinguishes a clinical investigator from an epidemiologist, and how he straddles both worlds. An internal medicine doc at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Stephen sees patients twice a week, and spends the rest of his time analyzing data, writing papers, and collaborating with colleagues.

I thought of Stephen for this feature post because I’m continuously impressed by the volume (and quality) of publications he produces. PubMed notes 64 articles authored by Stephen since 2008. A dual MD-PhD, he’s also got around 1,136 citations for his papers on diabetes, hypertension, the DASH diet, ARIC, and more. At AHA Scientific Sessions last November in Anaheim, California, Stephen presented his recent research on the DASH diet (read more in my post “Incorporating Scientific Sessions into Everyday Life”). In the few months since, he’s had 3 more first author papers go to print.

When asked how he balances work as a clinician and his research, he had some good pointers. While having protected research time from his K-award certainly helps schedule wise, his desire for his “research to be complimentary to what [he does] with patients in clinic” makes the straddle more seamless. While the topic, like blood pressure, may exist in both his worlds, the skills used are very different. “In clinic,” he starts, “you’re focused on that one patient, assessing priorities for that one visit. When you’re doing research, it’s macro, it’s population based.” The question that seems to drive Stephen is the desire to “understand diseases on a larger scale” and doing research to “move the needle of health towards benefitting more people”.

Switching gears, I launch into my next question.

“What do you feel are the keys to success as an early career investigator, whether from the clinical perspective or the research perspective?”

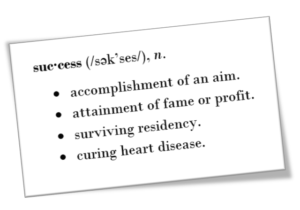

Without skipping a beat, he responds: “It depends on how you want to define success.”

The key to success depends on how you define it.

And that is so true. We’ve all read an article or two about work-life balance, setting goals, planning out your career, and the like. But Stephen lays it out simply: “Reflect on what makes you happy,” he recommends, “and think about what gets you excited.” Personally, as a doctoral student, the task of finding a dissertation topic (or that I don’t have one yet) is daunting. It’s easy to push it to the back of my mind and focus on coursework and current research projects. I don’t kick myself for doing that, though, because I have a plan. I choose my research projects and experiences carefully, with the goal of exposing myself to many different advisors, working styles, topics, and methods. An older student reflected on how she came upon her dissertation topic – when she tabulated all the projects she had worked on up to that point, they all centered around one topic. But she didn’t see the pattern until she sat down and thought it through.

Stephen identified his passion earlier as making a lasting impact on others in a positive way. Expanding on this idea seen in many researchers, clinicians, and public health professionals, he notes that “for some people, that is excellence in patient care…and [for] other people it’s policy and implementation and integration of scientific discovery…and for others, it’s doing the science.” His current role as physician-epidemiologist is clear in his passion: “I strive to include clinical excellence in my professional trajectory, and at the same time, incorporating scholarship and generating novel insights from data to guide our care.”

He notes that, like many of us, his trajectory hasn’t been a straight shot. Our conversation morphs into one of mentorship, as he describes his strategy as finding projects he feels passionate about, and then finding other people passionate about that, too. But when he first started as a trainee, that strategy often meant finding a mentor passionate about something, and then trying that passion on for size. Working with different people on a number of projects helped him identify what worked for him, what didn’t, and let him refine his writing process because, quoting a colleague Joe Coresh at the Welch Center: “to write a good paper, you have to write a lot of papers.”

After going through my first peer-review publication process just recently, I was heartened to hear Stephen admit that despite his now-refined writing process, his first paper did not go so smoothly. A math major in undergrad, Stephen relates that while his quantitative skills were great, it took him his first few papers to get the hang of the scientific writing process.

“Research is a very humbling process,” he tells me. “There are always going to be people who find issues with your work, or think there is a better way to say something. It can be discouraging. I remember being a trainee and just wanting to throw in the towel sometimes. But persevering through the process, knowing that the process is meant to make the product better, is a key mentality to have in research. Every time I’ve written a paper, I feel I have a better sense of what the message should be.”

He brings up a larger issue. When we see a successful person, we don’t often see the struggle behind the success. Learning from difficult experiences is often what catapults someone into success, and you can learn from their experience, too. You just have to ask.

Last month I wrote about “Making Epidemiology Make Sense for Clinicians”. Along the same lines, we wrap up our phone call with a final thought – how can clinicians and epidemiologists come together?

“Clinicians should feel empowered to make observations and ask practical questions.” Often, researchers are entrenched in data, not the day-to-day aspect of medicine, and “it can hamper the research process to not ask the right questions.”

When clinicians and epidemiologists partner together, they can leverage data to answer questions in a way that is very useful in the practice of medicine.

What plates are you spinning? I know I’ve got a few on board.

Bailey DeBarmore is a cardiovascular epidemiology PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on diabetes, stroke, and heart failure. She tweets @BaileyDeBarmore and blogs at baileydebarmore.com. Find her on LinkedIn and Facebook.