Registry Based Randomised Clinical Trials: A New Era in Randomised Trials

Adequately powered, appropriately designed and prospective randomized clinical trials are considered to be the gold standard for evidence generation for evaluating efficacy and safety of a treatment interventions, especially when compared to non-randomized or under powered trials1. The strength of these clinical trials design rely on selection bias being eliminated by the randomization process. In particular, a double-blinded randomization, where neither researcher nor participant know the exact intervention they are receiving minimizes bias2. However, randomized clinical trials suffer several limitations inherent in their design and thus international guidelines frequently require two or more supporting randomised trials3. Many of these trials suffer from the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria leading to questions about the trials real-world application4. Furthermore, large clinical trials are expensive and require considerable resources. Due to which, patients are sometimes subjected to treatment strategies that have not been verified for their safety or efficacy and for treatments.

In recent times, the interest is shifting towards registry based randomized trials as a novel way to conduct clinical trials. This concept allows a clinical trial to use existing data collection method and can provide enhanced patient enrollment. A randomized clinical trial needs identification of eligible patients, consenting, clinical characteristics at baseline, treatment randomization, and clinical outcomes. A registry by default collects many of these elements and by incorporating randomization, a prospective randomized trial can be included within the registry features. This will allow selective yet consecutive recruitment and automated follow up of the study participants.

Registry based randomized clinical trials (RRCT) are effective to assess hard clinical endpoints in large participant cohort and is particularly suited for open-label evaluation of commonly used therapeutic interventions5. RRCT may be limited in trials with interventions that need comprehensive safety assessments, pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic modelling and require strictly defined end points6. However, linking of numerous functionalities to a clinical registry might still be possible. Furthermore, RRCT design reduces cost and regulatory burden associated with trials6.

The RRCT concept was first instrumented within the SWEDEHEART ((Swedish Web‐System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) registry7 from Sweden in TASTE (Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Trial8. In which manual thrombus aspiration was prospectively evaluated as an adjunctive treatment to PCI for AMI with all-cause mortality as the primary end point. The registry was used to identify STEMI patients suitable for inclusion and the treating clinician further confirms the eligibility of the patient and obtained consent. All-cause mortality was routinely collected from the national population registry. No patients were lost to follow-up for the primary end point owing to automated, personalized identification number tracking. The main finding from the trial is that routine thrombus aspiration before PCI in patients with STEMI did not reduce the rate of all-cause mortality at 1 year or the composite of death from any cause, rehospitalization for myocardial infarction, or stent thrombosis at 1 year. Comparing it to the TAPAS (Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial, a single-centre trial that was not designed for the evaluation of clinical outcomes, thrombus aspiration was associated with a significant 40% relative reduction in all-cause mortality at 1 year9. In contrast to TAPAS, the TASTE trial was a large, multicentre study designed to have statistical power for the evaluation of all-cause mortality8. From the TASTE experience, the strength of RRCT is clear. Furthermore, the cost of such a trial is subsidized by the existing registry and willingness of investigators to participate for minimal monetary compensation.

SAFE PCI for women using NCDR CATH-PCI Registry10, DETOzX-AMI (Determination of the role of oxygen in suspected Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial using SWEDEHEART registry11, MINOCA-BAT (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03686696) (Randomized Evaluation of Beta Blocker and Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Treatment in MINOCA Patients) using SWEDEHEART & CADOSA (Coronary Angiogram Database of South Australia) registries are few other examples of such RRCTs.

The need for novel approaches to minimise the limitations of the randomised clinical trials are quite evident. The integration of clinical trials and real-world practice is critical to determine which interventions are efficient. In this context, the prospective RRCTs are a powerful and highly cost-effective tool to establish clinical evidence that might not otherwise be appropriately evaluated.

References:

- Jones DS and Podolsky SH. The history and fate of the gold standard. The Lancet. 2015;385:1502-1503.

- Altman DG and Bland JM. Treatment allocation in controlled trials: why randomise? BMJ. 1999;318:1209.

- Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM and Smith SC, Jr. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. Jama. 2009;301:831-41.

- Furberg CD. To whom do the research findings apply? Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2002;87:570-574.

- Yndigegn T, Hofmann R, Jernberg T and Gale CP. Registry-based randomised clinical trial: efficient evaluation of generic pharmacotherapies in the contemporary era. Heart. 2018;104:1562.

- James S, Rao SV and Granger CB. Registry-based randomized clinical trials—a new clinical trial paradigm. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2015;12:312.

- Jernberg T, Attebring MF, Hambraeus K, Ivert T, James S, Jeppsson A, Lagerqvist B, Lindahl B, Stenestrand U and Wallentin L. The Swedish Web-system for enhancement and development of evidence-based care in heart disease evaluated according to recommended therapies (SWEDEHEART). Heart. 2010;96:1617-21.

- Lagerqvist B, Fröbert O, Olivecrona GK, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Alström P, Andersson J, Calais F, Carlsson J, Collste O, Götberg M, Hårdhammar P, Ioanes D, Kallryd A, Linder R, Lundin A, Odenstedt J, Omerovic E, Puskar V, Tödt T, Zelleroth E, Östlund O and James SK. Outcomes 1 Year after Thrombus Aspiration for Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371:1111-1120.

- Svilaas T, Vlaar PJ, van der Horst IC, Diercks GFH, de Smet BJGL, van den Heuvel AFM, Anthonio RL, Jessurun GA, Tan E-S, Suurmeijer AJH and Zijlstra F. Thrombus Aspiration during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:557-567.

- Hess CN, Rao SV, Kong DF, Aberle LH, Anstrom KJ, Gibson CM, Gilchrist IC, Jacobs AK, Jolly SS, Mehran R, Messenger JC, Newby LK, Waksman R and Krucoff MW. Embedding a randomized clinical trial into an ongoing registry infrastructure: Unique opportunities for efficiency in design of the Study of Access site For Enhancement of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Women (SAFE-PCI for Women). American Heart Journal. 2013;166:421-428.e1.

- Hofmann R, James SK, Svensson L, Witt N, Frick M, Lindahl B, Ostlund O, Ekelund U, Erlinge D, Herlitz J and Jernberg T. DETermination of the role of OXygen in suspected Acute Myocardial Infarction trial. Am Heart J. 2014;167:322-8.

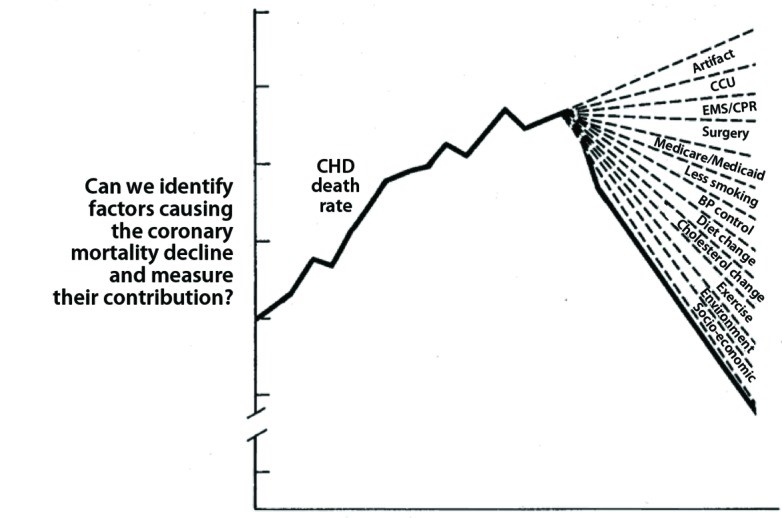

Cardiovascular disease is famously known as a disease that “rose from relative oblivion to the uno numero killer worldwide.” Globally, there were an estimated

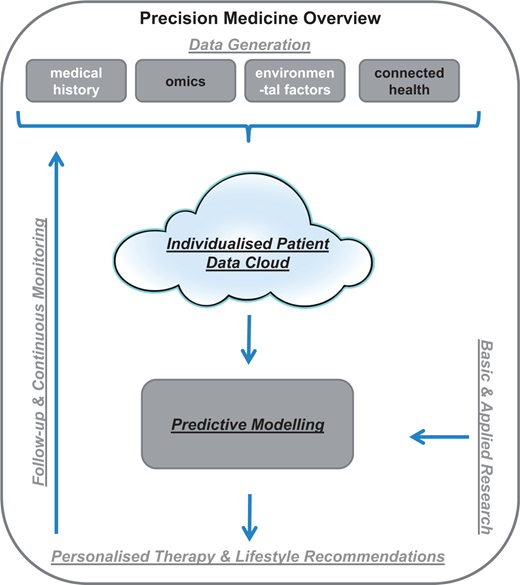

Cardiovascular disease is famously known as a disease that “rose from relative oblivion to the uno numero killer worldwide.” Globally, there were an estimated  Precision medicine represents a new approach where patient care is targeted towards prevention and cure considering individual differences of patients. The goal is to identify what’s best for a particular patient than what benefits the average population. As figure to the left shows, it is aimed to achieve through the accumulation of personalised data (clinical, biological, environmental & genetic) and computed predictive models that will inform logical therapy for each patient2.

Precision medicine represents a new approach where patient care is targeted towards prevention and cure considering individual differences of patients. The goal is to identify what’s best for a particular patient than what benefits the average population. As figure to the left shows, it is aimed to achieve through the accumulation of personalised data (clinical, biological, environmental & genetic) and computed predictive models that will inform logical therapy for each patient2.