2021 Chest Pain Guidelines from AHA21

2021 Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain was released in October 2021 and discussed in multiple sessions during AHA21. It was a collaboration between cardiologists, interventional cardiologists, cardiac intensivists, epidemiologists, and emergency medicine specialists. The team has focused on a symptom rather than a disease, making this approach unique. In the U.S, chest pain is the main reason for about 6.5 million emergency department encounters and the second reason patients seek medical attention in an emergency room. Only 5.1 % of ED visits with chest pain were found to have an acute coronary syndrome. It is imperative to distinguish between life-threatening and benign causes. The new guideline has provided recommendations and algorithms for assessing chest pain based on contemporary evidence. This short blog will summarize the top take-home messages.

In the new guideline, authors refrain from using the term “atypical” chest pain. They have argued that this term may be misinterpreted as benign in nature. They have changed the atypical term to non-cardiac, which is more specific in addressing underlying diagnosis. The guideline emphasizes the uniqueness of chest pain in women. It is estimated that cardiac causes of chest pain are underdiagnosed in this population. Since women are more likely to present with accompanying symptoms, health care professionals should consider these symptoms while obtaining a history. An electrocardiogram should be obtained and reviewed for the presence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction within 10 minutes of ED arrival. Furthermore, in patients with intermediate to high clinical suspicion for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a supplemental electrocardiogram on leads V7 to V9 is needed to rule out posterior MI. Cardiac troponin is a biomarker of choice for detecting myocardial injury. Authors recommend against the measurement of creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK, CK-MB) and myoglobin for diagnosis of acute myocardial injury.

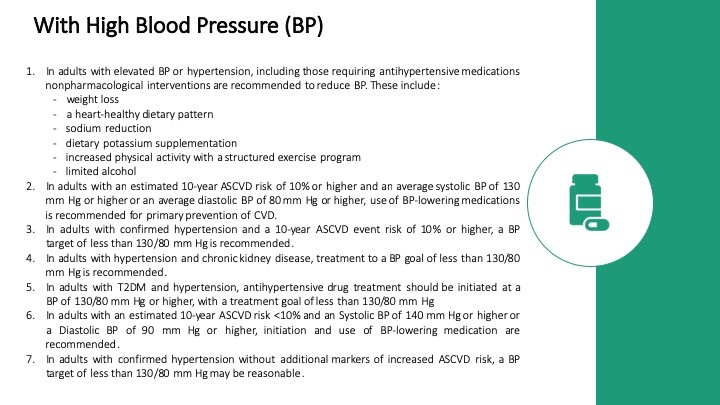

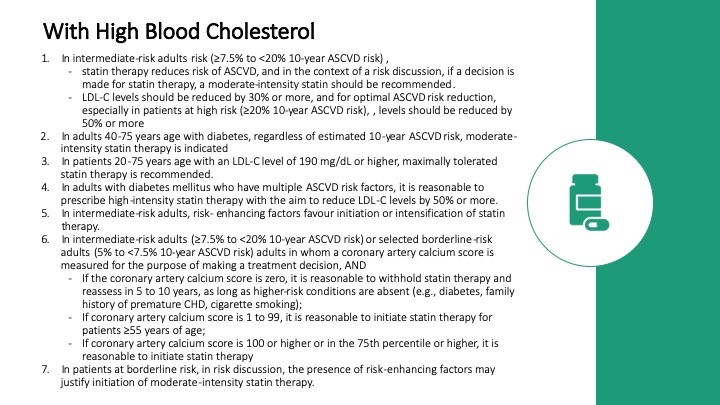

The guideline panelists have revised the term coronary artery disease (CAD). Previously, CAD was defined as the presence of significant obstructive stenosis (i.e., ≥50%). This revision has broadened the term CAD to those with identified non-obstructive atherosclerotic plaques on prior anatomic and functional testing. This approach may prevent those with non-obstructive CAD from getting overlooked and deprived of optimized preventive measures. The guideline also provides recommendations on selecting optimal diagnostic testing for patients with chest pain. A health care professional should first consider the pretest likelihood of CAD before selecting a cardiac test modality. The guideline emphasizes the lack of need to pursue any diagnostic test in those with low CAD risk. A coronary artery calcium score may be appropriate for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk stratification. In patients at intermediate-high risk of CAD, based on age (≥65 years of age vs. < 65 years of age) and suspicion of a degree of coronary obstruction, the guideline recommends further anatomical testing. Coronary computed tomography angiography is favored among patients at a younger age or less obstructive CAD suspicion, while stress testing is preferred among older patients or more obstructive CAD suspicion. The goal of CCTA is to rule out obstructive CAD or to detect non-obstructive CAD. If an evaluation is required, it will also provide further information about the anomalous coronary arteries, aorta, and pulmonary arteries. Ischemia-guided management is the goal of stress imaging. It can provide information when prior CCTA is inconclusive and about myocardial scar tissue and coronary microvascular dysfunction.

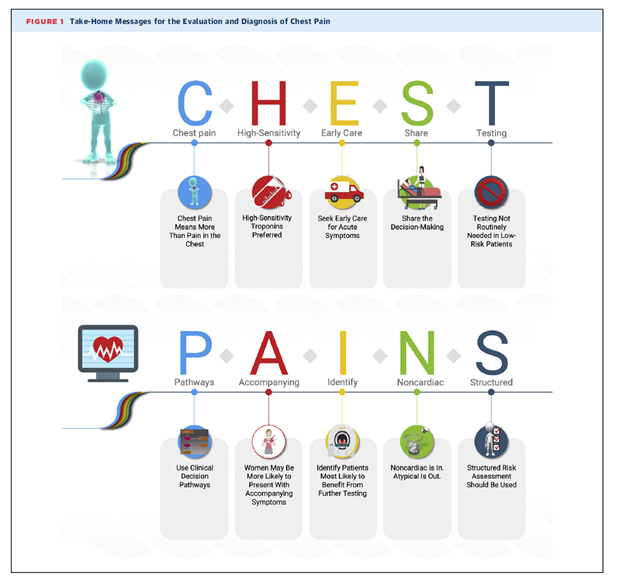

The term CHEST PAIN represents the take-home message of the guideline, as shown in the figure. Each alphabet has a meaning. C: Chest pain means more than a pain in the chest, H: High sensitivity troponin is preferred. E: seek Early care for acute symptoms. S: Share the decision-making, T: Testing not routinely needed in low-risk patients. P: use clinical decision Pathways. Accompanying: women may be more likely to present with Accompanying symptoms. I: Identify patients most likely to benefit from further testing. N: Noncardiac is in, and atypical is out. S: Structured risk assessment should be used.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”