Let’s add Stress Reduction as the 8th step in the American Heart Association’s “Life’s Simple 7”

February is Heart Month! An entire month dedicated to heart disease awareness in our community. During this month, we also educate the community on why heart disease is a women’s biggest threat. After all, heart disease takes more lives than all cancers combined. Globally, that equates to one woman dying every 80 seconds. More recently, research has revealed an emerging heart disease epidemic in young women resulting from uncontrolled risk factors such as obesity, blood pressure, elevated cholesterol and diabetes.

The good news is that 80% of heart disease can be prevented through risk factor management – this journey begins with a baseline assessment with a clinician. Starting this journey early is critical – research has demonstrated that if a woman can reach 50 without developing a major risk factor for heart disease, her lifetime risk for heart disease is only 8%. By contrast, women who have 2 or more risk factors for heart disease at 50 have a 50% risk of developing heart disease.

Heart month is a great time to start your journey to #knowyournumbers. The three most important numbers to check are:

- Blood Pressure

- Cholesterol

- Blood Sugar (A1C)

It’s also a great time to review your diet and exercise plan with your physician.

Furthermore, in women, an increasingly important aspect of cardiovascular health is the presence of psychological, psychosocial, and emotional stress. Well-established epidemiological data has shown that psychological risk factors such as anxiety, depression, work-related exhaustion, or perceived home stress are significantly associated with heart attacks in women (1). Another large study of young women presenting with heart attacks revealed that women reported higher amounts of perceived stress before their heart attacks symptoms compared with men. Overall, women reported worse baseline physical and mental health before heart attacks compared with men (2). Therefore, an important assessment of a woman’s current emotional health status is imperative in my initial cardiac workup, particularly for women.

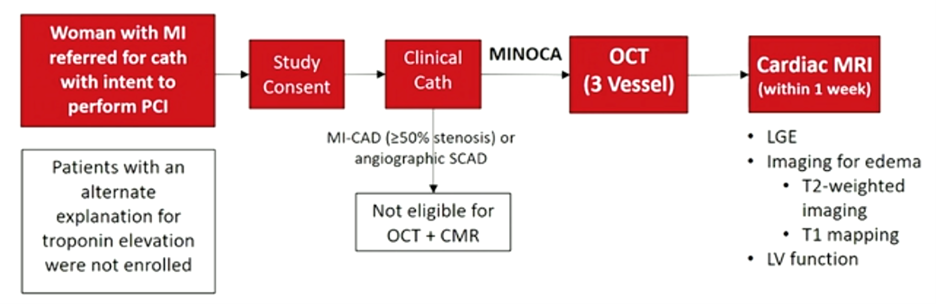

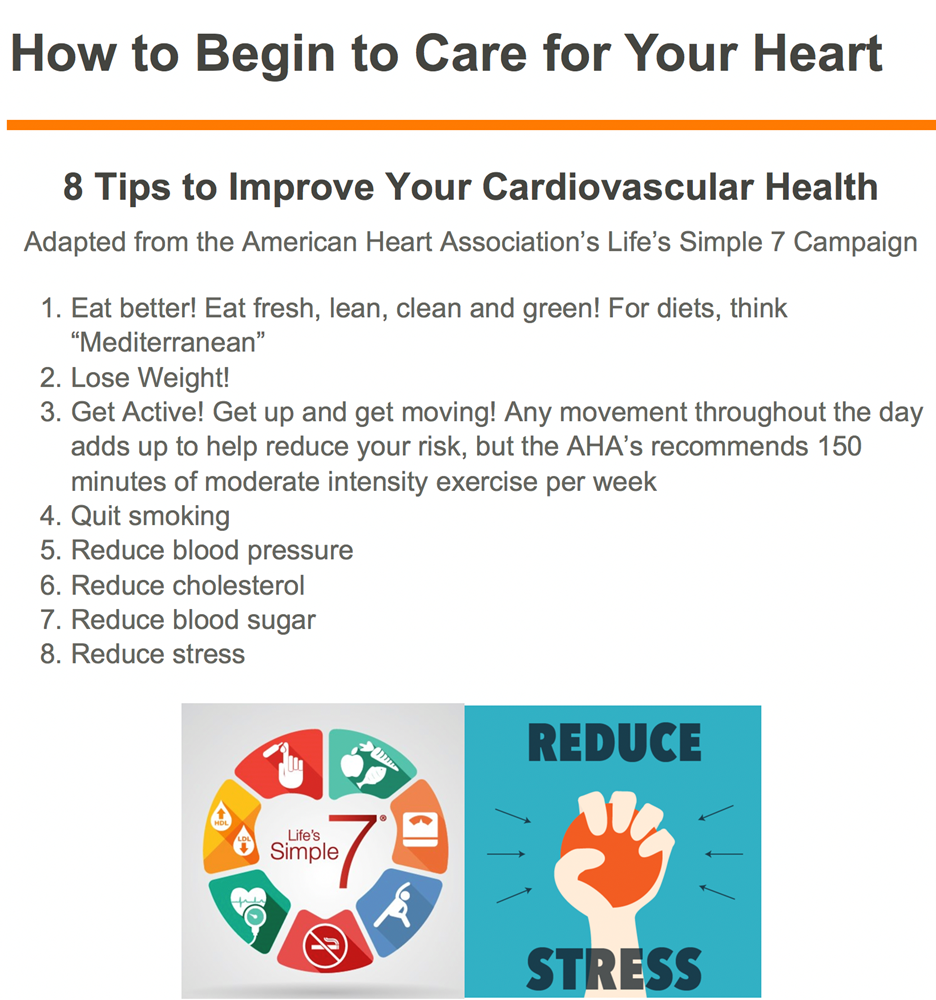

During the initial consultation and subsequent follow-up visits, I focus on learning details about my patients’ lifestyle habits including eating patterns, physical activity/exercise routine, sleep hygiene, and stress levels. The key is to begin the discussion to open the door to awareness of how one’s lifestyle could be setting them up for the greater cardiovascular risk. The American Heart Association (AHA) has created a campaign for workplace health called “Life’s Simple 7” which defines ideal cardiovascular health in terms of seven risk factors (Life’s Simple 7) that people can improve through lifestyle changes: smoking status, physical activity, weight, diet, blood glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure. While I have leaned on AHAs “Life’s Simple 7”, I have added a very important 8th step to reduce cardiovascular risk in my patients: Reduce Stress.

When it comes to my women patients, I have found that they are usually suffering from a compounded impact of accumulated stress from both families, interpersonal relationships, and/or work. To help improve mental health, I recommend practicing the 4-7-8 breathing technique, prioritizing self-compassion, and focusing on gratitude. These simple steps help to create the mindfulness that helps mitigate stress and its potential impact on the heart.

The 4-7-8 breathing technique popularized by Dr. Andrew Weil in the West is based on the ancient Indian yogic breathing technique called Pranayama. This technique can slow down the nervous system that controls the “stress response” and in turn enhance the relaxation response in the body and the heart. It is easily accessible for my “busy” women patients as it can be performed from any location without any equipment. The goal is to ensure your exhalation is twice as long as your inhalation.

While there are officially 8 total steps to use this technique, I often ask my patients to simply inhale for the count of 4 in the nose, hold for a count of 7, and exhale for a count of 8 through the mouth.

Self-compassion is another effective way to enhance well-being and reduce burnout. Self-compassion is the act of directing compassion towards oneself when dealing with a failure, a personal struggle, or negative thoughts about oneself. Self-compassion leads with kindness and understanding instead of self-criticism and self-judgment in response to personal shortcomings. Recent studies on self-compassion have revealed a direct relationship between self-compression and feelings of greater well-being.

Gratitude is another way to return kindness to one’s life. It is the quality of being thankful. The creation of a gratitude practice in one’s life may take many different forms: journaling, meditation, active daily reminders or even prayer. The common theme is opening the emotional heart to recognize and appreciate the simple pleasures in life which may be overlooked during times of stress. It is about cultivating a sense of thankfulness for what you have rather in your life no matter how small or simple.

Last year prior to a women’s heart disease awareness lecture series I delivered, I created a handout adapted from AHA’s “Life’s Simple 7” and added the additional 8th step: Reduce Stress. [See caption below] The details of how to actually begin that journey of self-awareness of perceived stress as well as important stress reduction techniques can now be found in this blog and hopefully will find their way to our patients.

Reference:

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S et al. INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): a case-control study. Lancet. 2004; 364:937–952.

- Xu X, Bao H, Strait K et al. Sex differences in perceived stress and early recovery in young and middle-aged patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015; 131:614–623.

- Life’s Simple 7. https://heart.org/en/professional/workplace-health/lifes-simple-7. Accessed 2/14/2021

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”