Self-Compassion: A Potential Antidote for Physician Burnout

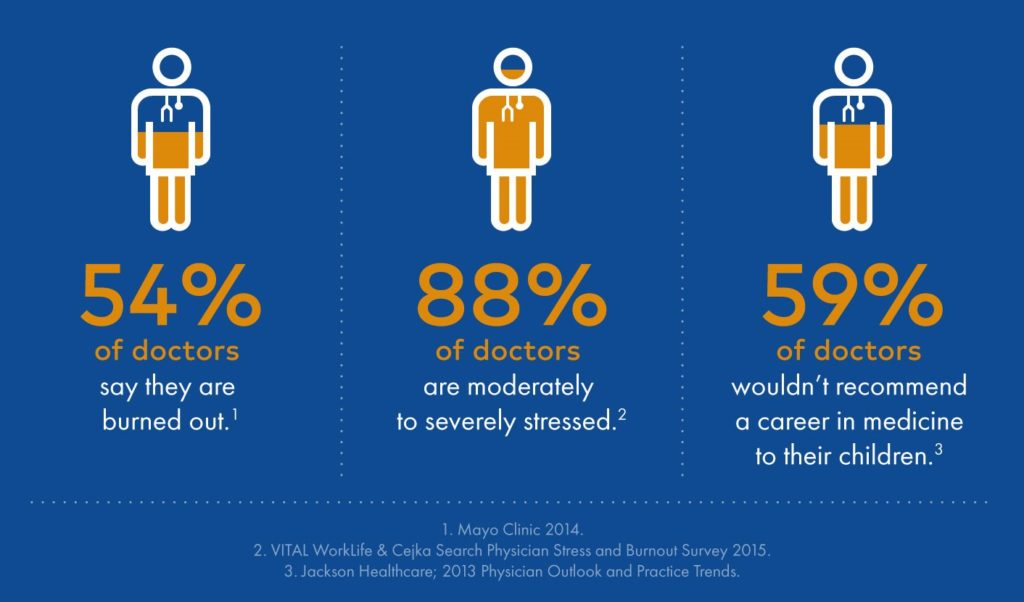

Physicians have been facing a crisis for years: Burnout. As defined by the 11th Revision of the International Classifications of Diseases (ICD-11), burnout is a syndrome of chronic occupational stress that is not managed successfully. It is further characterized by physical and emotional dimensions which include: 1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; 2) increased feelings of isolation, “separateness”, negativism, or cynicism related towards one’s job; or 3) reduced professional efficacy. (1) A recent survey found that more than 1 in 3 cardiologists in the U.S. report experiencing burnout. Women and mid-career cardiologists experience even higher rates of burnout. The data tells a similar story for the broader healthcare professional community: 35-54% of U.S physicians and nurses and 45-60% of medical students and residents have been reported to experience burnout (2). Burnout creates a perpetual state of exhaustion truly impairing physician’s ability to care for others in a safe, effective, and efficient matter which heightens negativity that may already be pervasive in one’s life. This cycle opens the door to harsh self-judgment or self-criticism and feelings of low self-esteem as well as depression. We not only have to break the cycle of burnout but also need to address the deep struggle of a harsh inner critic. Self-compassion can serve as a potential antidote for physician burnout.

The Need for Self-Compassion as a Physician

Compassion is defined as a sympathetic concern for the suffering of others. (3) As physicians, we know compassion. Compassion, empathy, and altruism play a key role in the patient-physician relationship. It is the cornerstone of our communication. Burnout, with its characteristic loss of empathy, can challenge even the strongest presence of humanism in our patient-physician relationships. Despite the exhaustion, many physicians are able to push through burnout for the sake of patient well-being. However, we are often most challenged to treat ourselves with the same level of compassion as we treat our patients or others. Burnout can accelerate feelings of professional inadequacy that can lead to a state of deep suffering: negative thoughts about one’s self, one’s professions, and one’s workplace. Additionally, it can become isolating with a tendency to feel alone in our suffering. While physicians may not always be aware of their level of self-criticism, it is, in many cases, ubiquitous among physicians.

For many physicians, self-criticism can be a strong source of motivation. The trade-off, however, can be quite harmful. Self-criticism deepens the stress-induced threat-based system in our brain that actually directs the harmful stress response back to ourselves (the source of our criticism). Perpetual self-criticism is closely linked to chronic stress, burnout, and depression. Self-compassion can break the cycle of self-criticism. Recent studies on self-compassion have revealed a direct relationship between self-compression and feelings of greater well-being. Self-compassion is the act of directing compassion towards oneself when dealing with a failure, a personal struggle or negative thoughts about oneself. Self-compassion leads with kindness and understanding instead of self-criticism and self-judgment in response to personal shortcomings (4).

Defining Self-Compassion

Dr. Kristen Neff, a pioneer in the field of self-compassion research, defines self-compassion in three components:

- Self-kindness – characterized by approaching oneself with warmth and understanding versus self-judgment, anger, or negative emotions when confronted with feelings of failure or inadequacies. Self-kindness sits at the core of self-compassion.

- Common humanity – the understanding that when a mistake happens or something does not go our way, it is part of a shared human experience rather than a state of “isolation”. Often times we can feel as though we are the only ones experiencing negative outcomes overcome by an overwhelming sensation of “why me”. Self-compassion recognizes that these outcomes are a part of a shared human experience.

- Mindfulness – the state of being aware of the present moment is an essential part of self-compassion. It steadies the mind to be present and helps curtail negative reactivity from one’s emotions. It is a non-judgmental state of mind where one can observe his or her emotions passively such that we avoid becoming “over-identified” by our emotions (4).

Self-compassion has been identified as an effective way to enhance well-being and reduce burnout for healthcare professionals (5). Ultimately, the practice of self-compassion is a skill. For physicians, it should be considered one of the essential skills for our personal and professional health. The more we practice self-compassion the more compassion we will have to give our patients. For more information about how you can incorporate self-compassion in your life check out the resources listed below.

References:

- Burnout an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Disease. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases Accessed: 1/10/2020

- Mehta, LS et al. Practice factors affecting cardiology wellbeing: The American College of Cardiology 2019 Burnout Study. Presented March 28, 2020. ACC 2020.

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/compassion Accessed: 1/10/2020

- Neff, K. (2011) Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Neff, KD et al. Caring for others without losing yourself: An adaptation of the Mindful Self-Compassion program for healthcare communities. Journal of Clin Psychol. 2020;1-20.

Resources for physicians to learn more about self-compassion:

- “Self-Compassion for Caregivers” by Kristen Neff https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJ9wGfwE-YE&feature=youtu.be

- An Exercise to Change Your Critical Self-Talk by Kristen Neff https://self-compassion.org/exercise-5-changing-critical-self-talk/

- Self-Compassion by Kristen Neff https://self-compassion.org/

- Center for Mindful Self-Compassion. https://centerformsc.org/

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”