State of the Union: Cryoablation vs Radiofrequency Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in the United States

Background

The concept of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF) was pioneered by Michel Haissaguerre from Bordeaux, France. In their landmark paper, Haissaguerre et al. described that the majority of triggers for atrial fibrillation (AF) can be mapped in the sleeves of muscles that extend into the pulmonary veins, and ablating these triggers leads to freedom from AF 1. This approach ultimately evolved into pulmonary vein isolation which remains one of the most commonly performed electrophysiological procedures today.

Essentially, the two common approaches involve radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or cryoablation (CRA). In general, most of the catheter guidance in RFA is with the help of electroanatomical mapping, and point by point lesions are made by heating the tissue, but it has a longer operator learning curve. CRA requires more extensive fluoroscopic guidance and can create circular lesions in a single step using a balloon that causes cellular necrosis by freezing the tissue 3. Since these two techniques differ in the source of energy, fluoroscopy time, need for electroanatomic guidance, learning curve, and procedure time, an important question arises: what is the best energy source to perform catheter ablation?

Multiple randomized controlled trials and observational studies have attempted to answer this question. A recent meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials and 34 observational studies that included 7951 patients undergoing CRA vs 9641 patients undergoing RFA showed that over a mean follow up of 14 ± 7 months, CRA reduced the incidence of AF recurrence as compared with RFA (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.78-0.94; p=0.001) . While the rate of phrenic nerve palsy was higher in CRA, rates of other complications like pericardial effusion, tamponade, and vascular complications were lower as compared with RFA. Interestingly, CRA procedure time was shorter than RFA by almost 20 mins4.

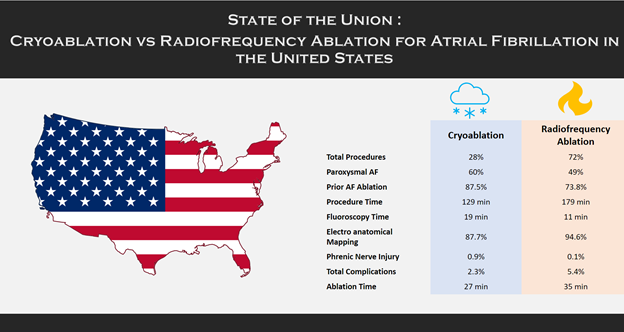

While this meta-analysis is based on results of multiple randomized and observational studies done under controlled settings, there is a paucity of real-world data comparing CRA vs RFA. This important question was addressed by Friedman et al in their analysis of Get With The Guidelines® – Atrial Fibrillation (GWTG-AFIB) registry 5 which gives a comprehensive understanding of the state of union regarding CRA vs RFA for AF (Figure 1)**.

GWTG-AFIB Registry

It is a large hospital-based quality improvement registry that is based on a partnership between the American Heart Association and Heart Rhythm Society and contains data on patients with AF or atrial flutter who have an overnight stay at a hospital in the United States 6.

Research Question

What are the differences in real-world patient and peri-procedural characteristics and in-hospital outcomes between CRA vs RFA?

Patient Characteristics

In total 5247 patients were included with 1465 undergoing CRA and 3782 undergoing RFA at 33 different sites. More patients undergoing CRA had paroxysmal AF (60% vs 48%) and no prior history of AF ablation (87.5% vs 73.8%) with similar CHA2DS2-VASc scores5.

Procedural Characteristics

The procedure times were shorter with CRA (129 min vs 179 min, p<0.001) but the ablation times were similar (27 min vs 35 min, p=0.15). There was an increase in fluoroscopy time with CRA vs RFA (19 min vs 11 min, p<0.001). The use of intracardiac echocardiography and electro anatomic mapping were less common with CRA; 87.3% vs 93.9%, p<0.001 and 87.7% vs 94.6%, p<0.001 respectively 5.

In-Hospital Complications

Phrenic nerve injury was more common with CRA (0.9% vs 0.1%, p=0.0001). Total complications were more with RFA (5.4% vs 2.3%, p<0.0001) however these were attributed to more volume overload and other events. The risk of any complication was less common with CRA (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25-0.79, p =0.0056).

Implications

This study gives an important insight into the contemporary practice of CRA vs RFA in the United States. Overall, despite the increasing popularity of CRA, RFA still remains the most common type of catheter ablation for AF. It appears that patients undergoing RFA are in general more complex with a history of prior ablation or persistent AF, and more likely to have co-morbidities like heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. These differences in the patient characteristics like history of persistent AF may explain the observed differences in complications with RFA. Another interesting observation from this study is that more RFA were performed at academic/teaching hospitals (91.7% vs 83.8%) and the likely explanation is that the procedure requires more time and expertise than is generally available at larger academic centers.

An encouraging observation from this real-world cohort of patients is that the rate of nerve injury was lower in both CRA (0.9%) and RFA (0.1%) arms as compared to the large randomized FIRE and ICE trial 3 (CRA 2.7%, RFA 0%) and comparable to the meta-analysis by Fortuni 4 (transient phrenic nerve palsy with CRA 3.2% and with RFA 0.05; permanent phrenic nerve palsy with CRA 0.6% and with RFA 0.04% ).

Future Directions

In future a comparison of longitudinal outcomes like recurrence of AF, quality of life, AF symptoms, incidence of heart failure, incidence of stroke, incidence of thromboembolic complications, AF related hospitalizations, cost of care and mortality, between CRA and RFA will be important.

Figure 1: Comparison of patient and periprocedural characteristics and in-hospital complications between cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation from Get With The Guidelines® atrial fibrillation registry.

**This study was funded by a GWTG-AFib Early Career Investigator Award.

References

- Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous Initiation of Atrial Fibrillation by Ectopic Beats Originating in the Pulmonary Veins. New England Journal of Medicine 1998;339:659–666. doi:10.1056/NEJM199809033391003.

- Wellens Hein J. J. Pulmonary Vein Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2000;102:2562–2564. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.102.21.2562.

- Kuck K-H, Brugada J, Fürnkranz A, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Chun KRJ, et al. Cryoballoon or Radiofrequency Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;374:2235–2245. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602014.

- Fortuni F, Casula M, Sanzo A, Angelini F, Cornara S, Somaschini A, et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing Cryoballoon Versus Radiofrequency as First Ablation Procedure for Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2020;125:1170–1179. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.01.016.

- Friedman DJ, Holmes D, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Frankel DS, Knight BP, et al. Procedure characteristics and outcomes of atrial fibrillation ablation procedures using cryoballoon versus radiofrequency ablation: A report from the GWTG-AFIB registry. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2021;32:248–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.14858.

- Get With The Guidelines- AFIB Registry. WwwHeartOrg n.d. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/get-with-the-guidelines/get-with-the-guidelines-afib (accessed March 15, 2021).

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”