Setting Expectations for AI Models in Medicine

Artificial intelligence is a hot topic in every field, and these algorithms are being widely used in scientific research. Particularly in my field of genetics and genomics, machine learning methods are invaluable for gleaning insights from large amounts of highly dimensional data. But there are many things to consider before applying AI and ML in a clinical setting, when real people are on the other end of the predictive model. It is important to set expectations for what AI can and cannot accomplish and what is needed for a broad application of AI in medicine in the future. In the session “Hype or Hope? Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Imaging”, presenters gave a great overview of the applications of AI, its limitations, and the advancements that are needed for a wide application of AI in medicine.

Dr. Geoffrey Rubin described many different scenarios in which AI can be deployed. Specifically, he talked about how AI can be used in predictive analytics to make test selection and imaging more efficient, in image reconstruction to reduce noise, in image segmentation to identify regions of interest and provide quantitative analysis, and in interpretation to derive unique characteristics that cannot be measured directly, identify abnormalities, and create reports. In addition, Dr. Tessa Cook explained in greater depth how AI can be used as clinical decision support to incorporate diverse data types and aid in proper test selection. Dr. Damini Dey also discussed how AI can improve diagnosis and prediction, characterize disease, and personalize therapy. Overall, it is important to determine where AI can provide the greatest value while introducing the least amount of risk.

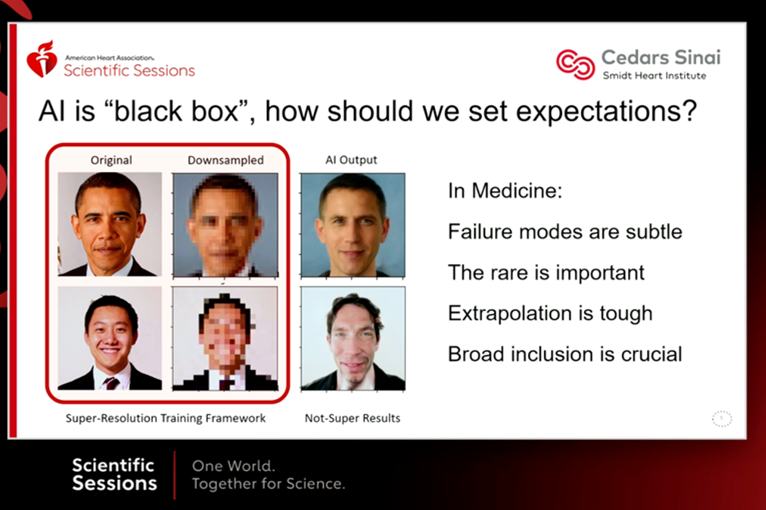

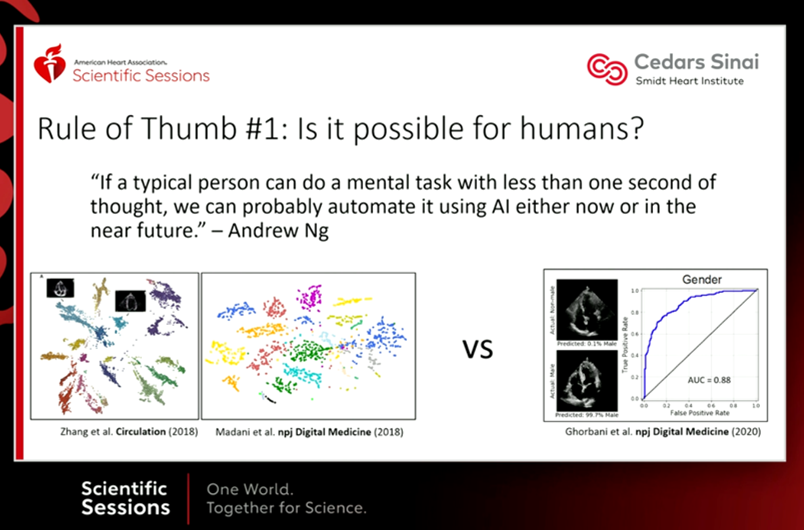

However, there are many limitations to AI and ML models. First, as Dr. David Ouyang noted, because these models are trained by humans, they can only perform tasks that a human could theoretically do. AI just performs these tasks faster, more consistently, and at a larger scale. He noted that these models are not effective unless trained on broad underlying datasets, and that unless explicitly programmed, they do not accurately weight rare significant events. AI models can easily become uninterpretable black boxes, keeping experts from recognizing where they are failing. Dr. David Playford emphasized that due to these and other limitations, AI models are not yet clinically accurate in all areas.

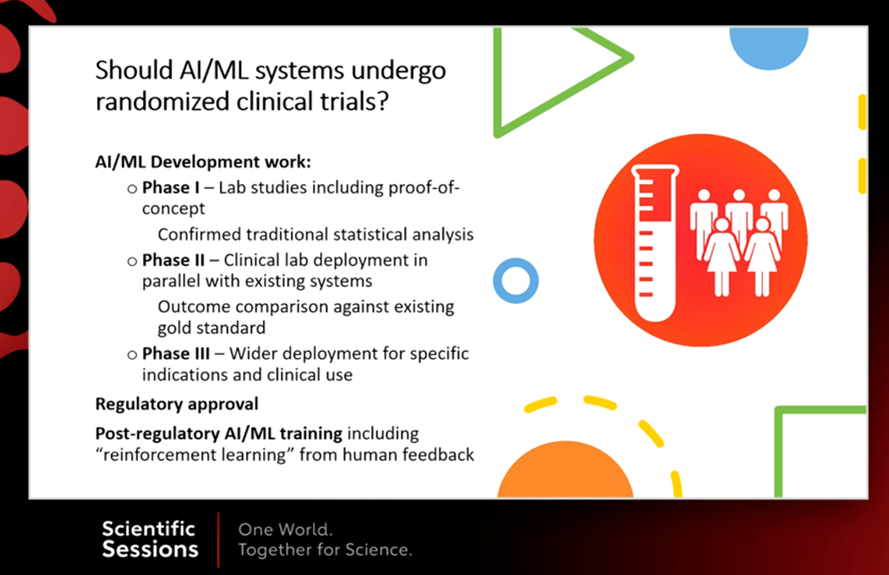

There are many steps that must be taken before AI models can achieve wide use in clinical settings. Dr. Ouyang suggests standardized baselines and open access to measure advancements among tools. Dr. Cook implements a “trust and value” checklist to assess how each tool was trained and tested, as well as what it can and cannot do, before using it for clinical decision support. Dr. Playford advocates for randomized trials to establish proof-of-concept and compare outcomes to the current standard of care. Most importantly, steps must be taken to reduce bias in AI models, which can negatively impact the care of underrepresented populations. Multidisciplinary collaborative teams can ensure that the data aligns with the clinical question being tackled, diverse yet consistent training datasets are being used, and methods such as transfer learning are implemented to produce more accurate predictions on previously unseen datasets. While AI can be an important tool in clinical decision making, it is ultimately the responsibility of each physician to ensure that AI tools are serving their patients as effectively as possible.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”