It was 4 am one winter night on call when I got paged:

“Youngish diabetic female, mid-thirties, chest pain for a few hours. Unremarkable ECG. Let me send troponins and see. Doesn’t seem cardiac.”

“Doesn’t seem cardiac”

Dismissed, just like that, because she was young, and because she was a woman.

A proper listen to her symptoms revealed that this could indeed, be cardiac. She was admitted, her troponins were raised, a coronary angiography done a few hours later showed an occluded principal obtuse marginal branch which was stented. She was symptom-free the same day.

Fortunately for her, a definitive culprit lesion in her coronaries could be identified, that was amenable to stenting and thus treated. For the majority of women with non-obstructive coronaries, presenting with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA)1 or ischemia with no obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA), investigations would very likely have stopped right there, with that normal coronary angiography. Dismissed.

CVD in women

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of mortality among women across the globe.2 Despite improved treatment algorithms and the enormous strides made in cardiovascular care, women continue to have worse clinical outcomes than men, partly owing to them being underdiagnosed, understudied and undertreated.

One size does not fit all: A spectrum of differences

The inherent biological differences between men and women, in addition to the socio-cultural attributes of gender, mean that women have very different characteristics of ischemia in terms of symptoms, triggers, and aetiologies.3

Symptoms: While chest pain is the predominant presenting symptom in both men and women in acute coronary syndrome (ACS), historically, women have been known to present with more “atypical” symptoms such as neck pain, fatigue, dyspnea or nausea, often triggered by emotional stress but even this time-honored notion has been challenged by a recent study that found that typical symptoms were more common among women and have greater predictive value in women than in men with myocardial infarction.4

Co-morbidities: Women with ACS are known to be older, with a clustering of risk factors and greater prevalence of co-morbidities.3 Particularly, diabetes, smoking and a family history of ischaemic heart disease have been shown to have a stronger impact on event rates among women.3 Younger women with ACS have been found to have a worse pre-event health status (both physical and mental) in comparison to men.5

The age paradox: Premenopausal women are thought to be relatively protected against CVD compared to similar-aged men, owing to favorable effects of estrogen on cardiovascular function and metabolism. Intriguingly though, recent studies report an increase in hospitalization rates of ACS among young women, despite a decline among younger men. The mechanisms behind these differences remain a fairly understudied area.

Delayed presentation: Women are also known to present later, frequently attributing their symptoms to a non-cardiac-related condition such as acid reflux, stress, or anxiety.2,3 This inaccurate symptom attribution, in addition to a lack of awareness of risk, and barriers to self-care in general, lead to a delay in seeking treatment, contributing to poorer outcomes.

Different etiologies: By virtue of an obstructed coronary artery, my patient got lucky in terms of prompt diagnosis and treatment. In about 10% of all patients, and in about a third of women, such a culprit coronary lesion cannot be identified on angiography.2,3 Furthermore, microvascular angina affects close to a half of patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries.7 This coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) is defined as the presence of symptoms and objective evidence of ischemia in absence of obstructive coronary artery disease, with blood flow reserve and/or inducible microvascular spasmAngina with no obstructive coronary arteries is twice as prevalent in women as in men, 7 and might also contribute to the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which is also more commonly observed in women.9

Women are still under-studied in clinical trials

In the face of such a formidable gender disparity in CVD, women continue to be under-represented in some areas of cardiovascular clinical trials, particularly in ischaemic heart disease and heart failure drug trials, the most common cardiovascular conditions affecting women. In fact, a number of pivotal cardiovascular drug trials of 2019 had less than a quarter of women enroll.12-15 Interestingly, the PARAGON-HF trial, where 51.7% of patients were women, found a heterogeneity in treatment response: women with HFpEF responded better to valsartan-sacubitril, with a 28% reduction (rate ratio 0.73) in the primary endpoint.

In a compelling 2018 editorial, doctors Pilote and Raparelli explore the practical reasons for under-enrollment of women in cardiovascular drug trials, notably male-patterned inclusion criteria and gender-related barriers to screening and participation in trials, such as caretaking roles and low socioeconomic status. While proposing interventions to mitigate this issue (childcare and such support for women during time spent as a research participant, inclusion criteria that consider sex differences in pathophysiology, prespecified subgroup analyses, etc.), they warn that such under-representation of women could lead to sex-biased outcome measurements and missed opportunities to transfer results in clinical practice.

The issue, in essence, is not just about researching CVD in women: even within this large cohort, differences in symptoms, presentation and outcomes, heterogeneity related to age, ethnicity and geographic locations exist. Why younger women with ACS tend to have unfavorable prognoses is an as-yet unanswered question, with huge scope for research, as is microvascular dysfunction, known to be more prevalent among women.

What can be done?

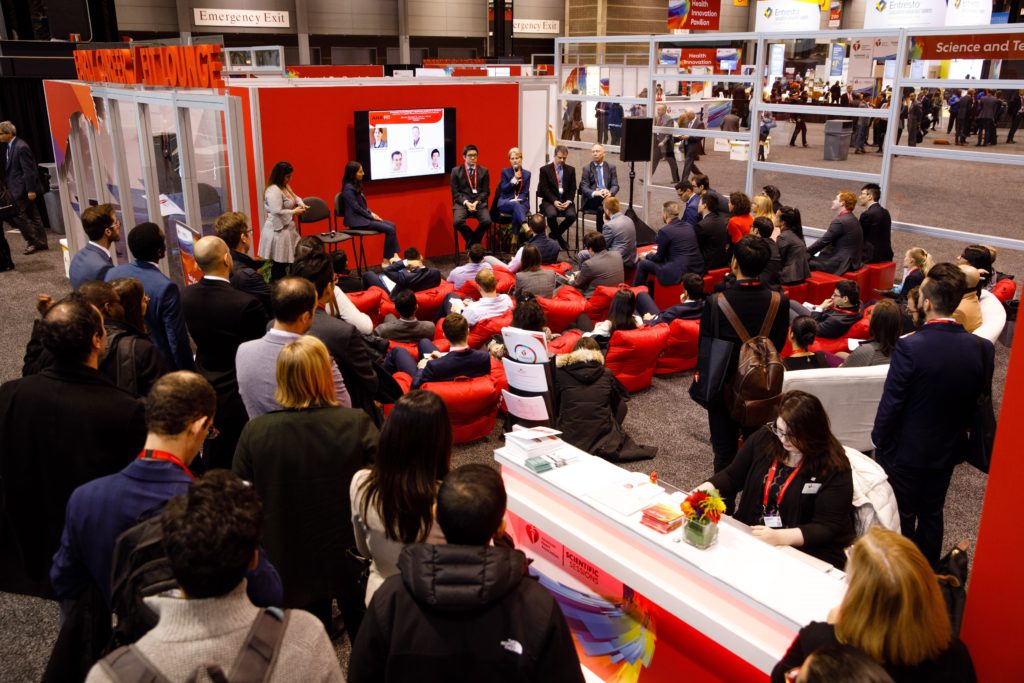

With February being national heart month, and the American Heart Association’s #GoRedForWomen campaign soaring at its highest, it seems like a good time to reflect on what can (and should) be done for women with CVD. Because there is plenty left to do.

Raise awareness: It’s vital that both women and men are aware that heart disease is as big a killer in women as in men. The AHA’s signature women’s initiative Go Red for Women (https://www.goredforwomen.org/) and the sub-initiatives of Wear Red Day are great platforms dedicated to increase women’s heart health awareness. The Women’s Heart Alliance (https://www.womensheartalliance.org/) is another organization working to promote gender equity in research, prevention, awareness and treatment.

Enroll more women in clinical trials: it’s important to identify barriers accounting for the low inclusion of women in clinical trials, and actively intervene to overcome them.

Women’s Heart Health Clinic: a number of programs have successfully initiated women’s heart health clinics, exclusively catering to the diagnosis and treatment of this often-underestimated patient group.

Get more women involved: at every level, be it as clinical trialists, advocates, physicians, nurses or other health-care providers.

As physicians, perhaps the best thing we can do for our female patients is to pay more attention. Don’t dismiss a symptom, because nothing should “not seem cardiac” until proven otherwise.

So, yes:

Listen to her.

Diagnose her.

Investigate her.

Study her.

Treat her.

And don’t just #GoRedForWomen in February. #GoRedForWomen throughout the year.

References

- Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): The Past, Present, and Future Management. Circulation. 2017;135(16):1490-1493.

- Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, Grines CL, Krumholz HM, Johnson Mnet al; American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916-47.

- Haider A, Bengs S, Luu J, Osto E, Siller-Matula JM, Muka T, et al. Sex and gender in cardiovascular medicine: presentation and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome. European Heart Journal (2019) 0, 1–14.

- Ferry AV, Anand A, Strachan FE, Mooney L, Stewart SD, Marshall L, et al. Presenting Symptoms in Men and Women Diagnosed With Myocardial Infarction Using Sex-Specific Criteria. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Sep 3;8(17):e012307.

- Dreyer RP, Smolderen KG, Strait KM, Beltrame JF, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, et al. Gender differences in prevent health status of young patients with acute myocardial infarction: a VIRGO study analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:43–54.

- Arora S, Stouffer GA, Kucharska-Newton AM, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Pandey A, et al. Twenty year trends and sex differences in young adults hospitalized acute myocardial infarction: the ARIC Community Surveillance Study. Circulation. 2019;139:1047–1056.

- 037137Jespersen L, Hvelplund A, Abildstrom SZ, Pedersen F, Galatius S, Madsen JK, et al. Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J 2012;33:734–744.

- Ong P, Camici PG, Beltrame JF, Crea F, Shimokawa H, Sechtem U,et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol 2018;250:16–20.

- Srivaratharajah K1 Coutinho T, deKemp R, Liu P, Haddad H, Stadnick E, et al. Reduced Myocardial Flow in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(7).

- Scott PE, Unger EF, Jenkins MR, Southworth MR, McDowell TY, Geller RJ, et al. Participation of Women in Clinical Trials Supporting FDA Approval of Cardiovascular Drugs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(18):1960-1969.

- Pilote L, Raparelli V. Participation of Women in Clinical Trials: Not Yet Time to Rest Our Laurels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(18):1970-1972.

- Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, Cohen DJ, Angiolillo DJ, Briguori C, et al. Ticagrelor with or without Aspirin in High-Risk Patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2032-2042.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, et al; DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995-2008.

- Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Bernlochner I, Wöhrle J, et al; ISAR-REACT 5 Trial Investigators. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019 ;381(16):1524-1534.

- Presented by Dr Judith S. Hochman at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions (AHA 2019), Philadelphia, PA, November 2019. https://www.ischemiatrial.org/system/files/attachments/ISCHEMIA%20MAIN%2012.03.19%20MASTER.pdf

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”