The Robotic Technology in Interventional Cardiology

The past few years have witnessed amazing advances in the robotic technology leading to its widespread utilization in both research and clinical aspects across multiple fields, including the cardiovascular field! I have recently attended a few conferences and the footprint of the robotic technology has been remarkable in each of them, emphasizing the great interest in the progress and utility of technology in our field. I decided to talk about robotic technology in interventional cardiology, the advantages and limitations of its use, and how I see it impacting the future of interventional cardiology.

- How long have we used robotic technology in the cath lab?

Robotic technology has been used in surgical specialties and radiation therapy since the mid-1990s. Then, robotics systems for endovascular interventions were developed and have been utilized for different percutaneous interventions, including simple and complex coronary and peripheral interventions, as well as other structural heart disease procedures, including atrial septal defect closure.

- Do we have scientific evidence-based trials assessing the robotic technology in interventional cardiology?

There are many prospective trials looking at robotic technology in both coronary and peripheral interventions. The two major studies are:

- PRECISE (Percutaneous Robotically Enhanced Coronary Interventions) trial: 164 patients with relatively simple lesions (>87% ACC/AHA type A/B; lesion length 12.2 6 4.8 mm), the investigators reported clinical success of 97.6%, technical success of 98.8% and > 95% median operator radiation reduction. Based on the results of this study, in 2012, the FDA approved the CorPath 200 System as the first robotic system for PCI.

- The RAPID (Robotic-Assisted Peripheral Interventions for Peripheral Artery Disease) trial, a prospective single-center, safety and feasibility study demonstrated the utility of the CorPath 200 system for robotic peripheral interventions. The study demonstrated 100% device technical and clinical success. No significant adverse events related to the device were reported, and based on this study, the CorPath 200 system received FDA approval for peripheral interventions.

- Advantages

- One of the main advantages of the robotic system in the cath lab is the reduction of radiation exposure for both the operators. The hazards of radiation are well-known and studies have demonstrated that the use of robots led to a reduction in radiation exposure [1]. Operators using the robotic system can either be in the cath lab several feet away from the radiation source or even in a separate room, where they can control the joystick and use the control pad to adjust the robot movements to control wires, the guide catheters and other devices (balloon, stents, etc..).

- Robots also help avoid wearing heavy lead aprons and thus decrease the orthopedic problems that many operators suffer from in the long run, including back pain and arthritis.

- Moreover, studies have also shown that robotic system use is associated with good precision and outcomes [1].

- Robots have been increasingly utilized with around 100 hospitals in the US currently using robots in the cath lab. This quick and widespread utilization of this new technology demonstrates not only how safe and successful the robotic system is, but also how easy and user-friendly it is.

- Limitations

In my opinion, this tool was developed to help operators, but not to replace them. Like any tool, the machine can potentially stop working, for a technical reason or other reasons, and at the end of the day, it is the physician’s responsibility to deal with the situation and solve the problem. In addition, the use of robotic system is limited in the following:

- The use of robotics in STEMI or bifurcation lesions has not been well-established yet, although reports and smaller studies have shown it can be performed safely.

- There are technical limitations of the robotic system, and if a lesion could not be treated, manual conversion is recommended.

- Limited devices used by the current generation of robotic technology: use of over-the-wire balloons, intra-vascular imaging catheter, or mechanical circulatory support is not available with the current generation of robotics.

- How will robots change the future of interventional cardiology?

The robotic technology has been increasingly utilized in multiple hospitals across the world. With more experience with robotic technology utilization, more knowledge and future upgrade of robotic systems, I think this tool will be increasingly utilized and updated to conform to the needs of patients, operators and different kinds of procedures and interventions; in fact, the robotic system is being studied in the utility of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures! Moreover, the utility of the robotic technology could potentially enable experienced operators to remotely perform complex interventional procedures in patients in different hospitals in rural or urban areas, different states, different countries or even different continents!

With the rapid progress in technology in all fields of our life, I think it is very important to establish and encourage more collaborations between technology and medical sciences, especially in procedural specialties, where precision and safety can be provided by these advanced robotics systems for optimal outcomes. I look forward to seeing how these technologies will evolve and transform our practice in the future!!

I would like to thank my colleague and friend, Dr. Jeff Hsu, for his help on this blog and for being an awesome senior buddy!!

References

- Mahmud et al: Robotic technology in interventional cardiology: Current status and future perspectives. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv.2017 Nov 15;90(6):956-962.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ccd.27209

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

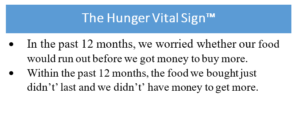

I know, we have to fit so much into each patient encounter that trying to fit in one more thing seems impossible. But a quick, simple strategy is to administer the

I know, we have to fit so much into each patient encounter that trying to fit in one more thing seems impossible. But a quick, simple strategy is to administer the

I instead work out in the hospital gym much more to try to stay active and have a positive outlet for when I am stressed. I often get asked, “what’s a good strategy for me to make it to the gym with our crazy schedule?” I’ve realized not everyone wants to go to the gym before work (which is my routine) but having small, achievable goals is the way to go. For example, try going one day before work, one day after work, and once during the weekend. You don’t need to go every single day to be healthy or stress-free. Having a few days per week in dedicated time slots will help create structure and not make going to work out feel like a chore.

I instead work out in the hospital gym much more to try to stay active and have a positive outlet for when I am stressed. I often get asked, “what’s a good strategy for me to make it to the gym with our crazy schedule?” I’ve realized not everyone wants to go to the gym before work (which is my routine) but having small, achievable goals is the way to go. For example, try going one day before work, one day after work, and once during the weekend. You don’t need to go every single day to be healthy or stress-free. Having a few days per week in dedicated time slots will help create structure and not make going to work out feel like a chore. me stay organized, but also my obsessive-compulsive personality LOVES to cross tasks off the list. If you get overwhelmed with the countless tasks you have to do, start keeping a list. This will help create structure, organization, and improve productivity.

me stay organized, but also my obsessive-compulsive personality LOVES to cross tasks off the list. If you get overwhelmed with the countless tasks you have to do, start keeping a list. This will help create structure, organization, and improve productivity.