When I decided I wanted to take the steps, in January of 2019, to pursue a residency in neurosurgery in the United States, I did what most of us do, I went to Youtube and saw how other people have studied. After a couple of days watching various videos, I felt overwhelmed since most of the videos entailed studying >9 hours, having a dedicated period exclusive for studying, and some of them suggested doing them during medical school.

All of those suggestions were not possible at the time for me, I had just graduated from medical school in December of 2018, and I had accepted a full-time job at Cedars-Sinai. Though I did question if I was going to be able to manage a full-time job on research and study for this life-defining exam, in the end, I pulled it off, and I took step1 in October of 2019 and step2 CK in may of 2020.

Before starting with my personal story of how I studied and managed my time to finish both USMLE while working, I just want to give you peace of mind to all of you that are not in the ideal situation of studying full time or that cant dedicate enormous time of study due to personal responsibilities. All roads lead to Rome; everyone is in a particular economic, social, and educational situation and what each one of us must do is to adapt and make the most out of our conditions!

So, let’s begin.

What was your approach to work and study at the same time?

When I faced this challenge, the first thing I did was to talk to my boss, Dr. Nestor Gonzalez, and my coworker Juan Toscano. I let them both know that while I was going to fulfill my job to the best extent of my abilities, they should know that I was also dedicating all my spare time both at work and outside from work to study.

I believe it’s crucial to the people you work with know what you are going through, and to me, this was extremely helpful, as there were times my coworker took over simple tasks and was very understandable to give me as much time as I could to study. Since my boss knew that I was taking this exam, I was able to take 2 weeks off before my exam date to dedicate 100% of my time to study.

For how long and how did you prepare for step1 and step2?

I started my step1 preparation on the third week of January 2019, when I started my job. During the first three weeks, I tried to get a sense of how my day to day was going to be at work, identify which hours would be ideal for studying either after work, before work, and also determine what the best time to do questions was, watch videos, read the first aid, etc.

After finishing the First Aid’s first pass (not extremely thorough, just a glimpse to see and get familiarized with the material), I outlined 3 phases of the study.

- The first (from Feb-April) would be dedicated to learn and review the theory, so 90% of my study day was to read the first aid, watch pathoma/Kaplan/sketchy, and a 10% was to do questions from different banks.

- The second (may-sept), Was dedicated 90% to Uworld and their respective review, and 10% to review the FA, pathoma, or any gap in my knowledge.

- The third and last (last week of sept-first of October), I only did questions. These were the 2 weeks my boss gave me to dedicate full time to study. I was able to do during this first week > 4 blocks a day with their respective review, and the last 5 days, I did practice 7 blocks as if I were taking Step1 (based on the recommendation of my friends Sandra Saade and Andre Monteiro), which was extremely helpful to gain endurance.

Total study time for Step1: From February-October

For step2 was easier to get organized since I would follow the same schedule and balance of work/study. I took a month’s break from step1 and started to study for step2 at the end of November. I studied from November until May 28, 2020 (one day after my birthday).

The approach was pretty similar to that of step1 with the caveat that I started from day 1 to do questions, and I also took one week off from my vacations to dedicate full time to prepare step2. The pandemic changed my preparation timing since we had to deal with the Prometric cancelations due to covid.

How was a regular workday during step1 and step2 preparation?

I would wake up at 6 am in the morning, and during the first 3 months, I commuted on the bus to my workplace, which was approximately 2 hours away. During these bus rides, I would read first aid; of course, I needed some noise-canceling headphones. I would highlight or repeat the things that I thought were most important. By the time I got to work, depending on the time, I would do 10 questions from any qbank before starting to work at 9 am. Usually, I would leave work by 4-4:30 pm to head back to my place.

On the way back, the commuting was equally long, sometimes a bit longer depending on traffic, so by the time I got to my home, I would have already read first aid on average 3 hours/day from Monday-Friday. I used to get home at around 7:00-7:30, cook dinner and my lunch for the next day, and after an appropriate break watching friends (I had just started to watch it), I would start my night study routine at 9:00 pm. From 9 pm until 1 am, I would watch pathoma, Kaplan, or sketchy videos. My goal from Monday to Friday was to study at least 6 hours per day, and I usually slept from 1 to 6 am (since med school, I had slept 5 hours a day)

In March, to make my commute more manageable, I got a bicycle, so I was biking halfway to work and the other half on the bus. This allowed me to get some exercise done, which I realized I was missing, and helped me to be more relaxed during this study/work period. From March until mid-June, I followed the same routine of reading first aid or doing my Anki cards on the bus and then studying at home until 1 am (or if I felt tired before 1 am). Some days, I had some spare time at work, so I tried to get some study done either by reviewing questions or reading the first aid.

From June-September, I wanted to increase my study time and try to use any free time to study. This routine of study/work with no other activities was highly tiring and stressful, and I knew that I needed something for my mental health, so I decided to join the gym. During this period, I wanted to use my time on my bicycle rides which were more than 50 min a day, so I converted all the pathoma videos into mp3 so I could listen to pathoma while I was riding my bike. Then I would do Anki or read FA on the bus, and at work would still review any question I didn’t finish the night before. Anki became my favorite and most used application, as during any break, at lunchtime, waiting for a meeting to start, or on the bus, I would do a couple of cards, and in the end, this helped me a lot. After work, I would get home at the same time (around 7 pm), eat dinner, and study until 9 pm. Then I would go to the gym and disconnect myself from anything related to the step. After my workout, I would study again until 1 am. Since I was increasing my study time during my former free time, I was trying to aim to have more than 6 hours of study a day, even though I had added the gym to my schedule.

I continued this pace until September before my 2 weeks of dedicated, with a few modifications. The closest I was getting to the date of my exam on October 8, I cut back even more from my free time, so once I finished listening pathoma, I transformed to Mp3 all the videos from Boards and Beyond (per Sebastian Gallo suggestion), and I would listen to them instead of listening to music, during my bike rides, while walking and even at the gym. This passive learning was a way of trying to make the most of the time during a working day.

I took 2 weeks off work, and I had the most significant visit at the worst time, from my mother Patricia, but it did give me an energy boost to finish up my studies. I stayed with my aunt Cristina and uncle mike in San Diego for the 2 most stressful weeks of my life so far, where I was studying from 9 to 11 hours a day before the test.

For step2, things were more manageable since I moved 15 min away from the hospital, and not commuting for more than 3 hours a day improved my life and study style a lot. My working schedule did not change, but my study times did. Since I was living so close to the hospital, I arrived at 6:40 am to the hospital and headed to the library to do a block of uworld and study until 9. I would work until 4:30 pm and then head to the library until 9:00 pm to keep doing questions or reviewing questions and then heading to the gym until 11-11:30. I would head back to my place and go to bed at around 12:30 to 1 am and then repeat the same schedule before the pandemic hit.

When the pandemic hit, we were sent to work from home. To adapt to working and studying in the same place as my roommates, that weren’t particularly quiet, I shifted my schedules to go to bed at 6:00 pm and wake up and begin my day at 11:00 pm. This allowed me to have enough space and time to study from 11:00 pm until my workday began at 8 am. After finishing work at around 4 pm, I would run 3 miles while listening to mp3 of MedEd, then had dinner and go to bed. After 3 cancelations from Prometric, I was able to schedule my step2 for the end of May.

How was your schedule on the weekends?

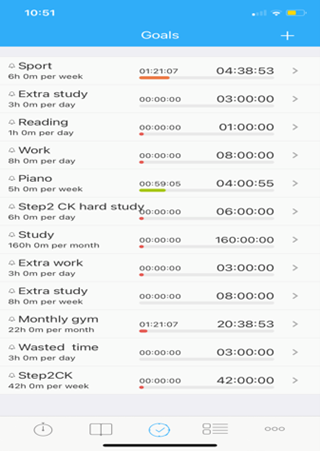

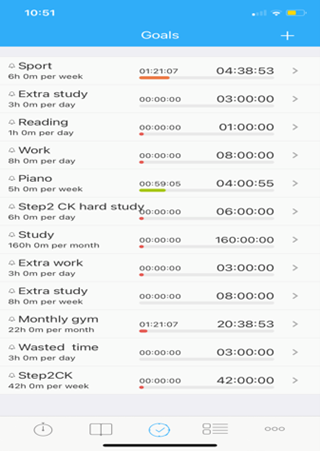

My weekends were the days that I studied the most and tried to make up for the study that I could not finish during the week and the sleep I did not get. I would do grocery shopping, take care of my place, and all the labor that entails with being an adult. I would study 8—9 hours on Saturday and Sunday. My goal per week was to study at least 42 hours. Some weeks were more brutal at work, or I was tired and couldn’t finish my 6 hours daily on the weekdays, making the weekends the perfect time to make up for the time that I did not study. The weekends were ideal for taking any assessment, whether Uworld Self-assessment or NBME.

When I joined the gym, I had another activity to do on the weekends, and I wish I had done it sooner to improve my mood at earlier stages of my study preparation.

How did you manage your time?

In the beginning, I was using just a regular clock and writing down how much I was studying per day on an excel sheet. This helped me keep track of how much I was studying, so I would stop the clock every time I grabbed my phone or took breaks. Then I found an app that changed my time management forever that is called aTimeLogger, which allowed me to set goals per day, week, and month depending on the activity that I was doing, that basically were studying, working, exercising, and wasting time (yes, to visually see how much time one wastes on Instagram, Facebook, youtube, is disturbing and helped me to reduce this screen time especially during quarantine).

As I said before, my goals were to reach a doable 6 hours per day or 42 hours of study per week and to do at least 6 hours of exercise per week for mental and physical health. Also to maintain a minumun of 5 hours of sleep per day which is used to be my normal sleeping time since medschool.

How did you balance your social life and working/studying?

Significant endeavors entail enormous sacrifices, so during this working/studying period for step1, I deleted all my social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and only kept Whats app to talk to my family and close relatives. Not having the distraction of social media on my phone helped me keep my objective clear, which was to pass with a good score step1/2, and that instead of grabbing my phone to check Instagram, I grabbed it to do Anki.

My social life was nonexistent during my study period. I did go out with my friend and coworker Juan maybe 6 times from January-December, and I saw my family a couple of times for brief moments. Since I had moved to a new country and new city, isolating myself from people was doable and extremely helpful to focus my energy only on studying and working. My first vacations during 2019 were for my dedicated 2 weeks for step1; they were not the ideal vacations but were necessary to study.

Any final suggestions for someone that is in a position similar to you?

These exams are complicated not only for the amount of time invested and information one has to learn but also the emotional pressure of having a test determining how feasible your dream of becoming a physician in the USA would be.

So, I would suggest:

- Committing thoroughly to studying and working, and trying to isolate yourself from most social engagements, talk to your family and friends; they will understand your absence in social engagements and not hold a grudge.

- Reducing, if possible, to zero social media from your phone and laptop. This helps you focus on the exam and not feel sad/anxious (which happened to me) because you see your friends and family partying or having fun while you are spending more time with Uworld than with another human being. Remember this is temporary; your life will get better after finishing the exams.

- Surround by people that are going through the same process and by those who already took the exam, we know how it feels, and we understand what you are and will go through. I have to say that talking out loud when I felt hopeless, tired, and overwhelmed was a vital pillar of this process of studying/working. So I want to give an enormous shout-out to my very patient friends and were there for me every step (Juan Velez, Sandra Saade, Sebastian Gallo, Andre Monteiro).

- Make time, even if little, to do your hobbies. In my case, it was going to the gym. It really changed my mood and gave me more mental stability, and to give yourself a break from studying.

- If you feel tired or burnout (because at some point you will), don’t be hard on yourself and take a break. I used to get very mad at myself when I was trying to study but could not focus, or I was falling asleep. Taking a break is also crucial to maintain sanity during difficult and extended periods of studying/working.

Last but not least is to look at the big picture and all that is at stake. While it is thought to work and study simultaneously, it taught me a lot of things, such as resilience, pushing my boundaries, and making the most out of a not ideal situation. When situations or conditions cannot be changed, one must adapt, and I’m glad I was able to deal with long commutes, working/studying, moving to a new country, and living alone for the first time in my life at the same time. In the end, it was worth it. I passed Step1 (239) and Step2 (236), and I’m thrilled that my dream to become a neurosurgeon is still intact.

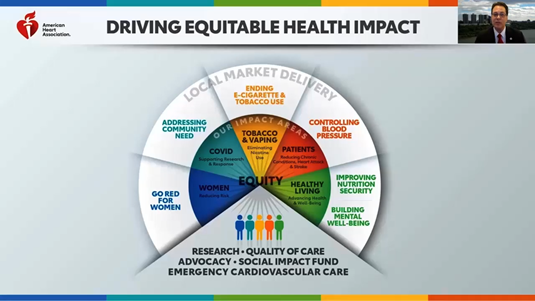

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

My name is Tony Prisco and I am a PGY-5 at the University of Minnesota in the Physician-Scientist Training Program. I am pursuing my fellowship training in cardiovascular diseases. I finished my PhD in 2014 focusing on mechanisms of angiogenesis induced by adult stem cells. Since then my scientific interests have transformed to mathematical studies, including fluid mechanics and artificial intelligence. The majority of my work since my PhD has focused on blood flow mechanisms in patients with mechanical circulatory support (ventricular assist devices and VA-ECMO). I had been hearing about various forms of artificial intelligence since at least 2014 but did not realize the potential clinical applications until I started my residency in 2016.

My name is Tony Prisco and I am a PGY-5 at the University of Minnesota in the Physician-Scientist Training Program. I am pursuing my fellowship training in cardiovascular diseases. I finished my PhD in 2014 focusing on mechanisms of angiogenesis induced by adult stem cells. Since then my scientific interests have transformed to mathematical studies, including fluid mechanics and artificial intelligence. The majority of my work since my PhD has focused on blood flow mechanisms in patients with mechanical circulatory support (ventricular assist devices and VA-ECMO). I had been hearing about various forms of artificial intelligence since at least 2014 but did not realize the potential clinical applications until I started my residency in 2016.