E-cigarette use is a health concern, but long-term consequences remain unknown

Recently, I happened to take a route home that led me through my local high school as the students were dismissed for the day. There was some traffic because of dismissal as students traveled home in their vehicles or were picked up by parents/guardians. As I inched along the path to the main road, the car ahead of me was being driven by a student, and I noticed he was vaping. With two small kids, I don’t get the privilege of observing teenagers too often, so it made me pause a bit to witness this. When I think back to my high school days, cigarette smoking was one of the salient issues with youth and substance use, and there were huge campaigns to limit tobacco use among adolescents. I was all too familiar with the D.A.R.E (drug abuse resistance education) program at every step of my education as an adolescent! But today, cigarette smoking is less common among adolescents than nearly 20 years ago.

As a cardiovascular epidemiologist, I’m aware of the available evidence and conflicting messages we receive about the costs and benefits of e-cigarette use among adults. But what is the message for youth? Is vaping as addictive as cigarettes, and does it offer similar health threats? And if so, are there programs in place to limit vaping? One thing is for sure, compared with our knowledge and evidence on decades of cigarette smoking, e-cigarette use and vaping research are still in their infancy, but a more explicit message is making its way through all the vapors.

The increasing use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS)) and vaping products among youth continues to be recognized as a significant public health challenge. Severe cardiopulmonary disease and related deaths have been associated with the use of electronic cigarettes. To emphasize the importance of stronger public health policies and guide therapeutic strategies on the short- and long-term risks of vaping, the recent AHA scientific statement provides background on the cardiopulmonary consequences of e-cigarette use (vaping) in adolescents. Vaping may pose longer-term health threats like nicotine addiction and cardiopulmonary damage.

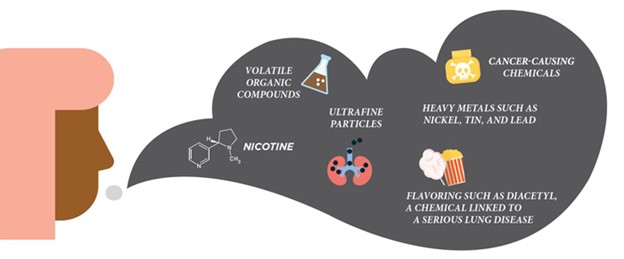

Figure 1. What is in E-cigarette Aerosol? CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/Quick-Facts-on-the-Risks-of-E-cigarettes-for-Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults.html

Vaping involves heating a liquid — typically containing nicotine or cannabis, flavorings, and other substances and additives — to produce an aerosol inhaled through a battery-powered device. E-cigarettes have grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry since entering the U.S. market in 2007 as a potential smoking cessation tool. Still, they also appealed to youth – with fruity flavor additives and nicotine salts, making it less harsh on the throat and easier to use by adolescents. Over the years, e-cigarette use among US teenagers showed a 19% increase between 2011 and 2018. Vaping is still prevalent among adolescents, but we have seen a decline in 2019, some of which may be due to reduced access or disease-related concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that in 2020, at least 3.6 million US youth, including about 1 in 5 high school students and about 1 in 20 middle school students, used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. Notably, public health has made significant strides over the past decade in lowering the prevalence of cigarette smoking among adolescents to its lowest rates in history – fewer than 6% of high school students have smoked a cigarette in the past 30 days, and fewer than 3% report being daily users. Although the benefits won’t be realized for about 30 years, this accomplishment is enormous and portends reductions in smoking-related disabilities and death for generations to come.

On the other hand, the big question is whether e-cigarettes and vaping will have a deleterious effect on youth. In November 2019, we saw the impact of acute vaping-associated lung injuries and confirmed vaping-related deaths linked to vitamin E acetate – a chemical additive in the production of e-cigarette products. These events warned that additives could be involved in adverse health effects of vaping. Besides nicotine, vaping liquids contain vegetable glycerin and propylene glycol, which are on the FDA’s generally recognized as safe (GRAS) list. However, these components were not evaluated for inhalation toxicology. Like vitamin E acetate, these GRAS components may be associated with adverse health outcomes once inhaled. Thus, the long-term effects of vaping on the lungs in youth and young adults are worrisome and need to be better understood.

Studies have found higher rates of wheezing, greater prevalence of asthma, and increased incidence of respiratory disease in youth who were e-cigarette users. Among young adults, e-cigarette use is associated with higher arterial stiffness, impaired endothelial function, increased blood pressure, heart rate, and sympathetic tone, increased levels of oxidative stress biomarkers, and pro-inflammatory white blood cells that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Subclinical cardiopulmonary disease can likely start early in adolescence among youth who vape. Overall, lung development continues into the early 20s. Therefore, adolescents who vape are potentially stunting or altering their lung development, limiting their full lung function potential, and increasing their risk of pulmonary disorders.

Statistically, the population health risk of vaping-related disease among adolescents depends on the prevalence and frequency of vaping. Many adolescents experiment with vaping or may vape only occasionally or socially, conferring in possible low health risk. But as informed by evidence from cigarette use, vaping for 20+ days per month may suggest a degree of dependence and greater health risks. Youth may also multiply their risk by smoking other substances like marijuana. Collectively, continued research into the cardiopulmonary health consequences of vaping in youth needs to weigh the contribution of marijuana smoking or vaping with e-cigarette use.

Primary care and public health strategies should protect young people and limit unnecessary exposure.

The AHA scientific statement concludes with several major recommendations for reducing and preventing youth vaping:

- Developing better measures to reduce youth access, including strict age verification at places of sale

- Prohibiting the marketing of e-cigarettes to youth

- Education of healthcare stakeholders, students, and their parents regarding realistic concerns about e-cigarette use

The recommendations do come with some controversy. Dr. Neal L. Benowitz mentions in his commentary of the scientific statement that “to limit access [among youth] could be even stronger if e-cigarette sales were limited to adult-only tobacco specialty stores.” He also offers that AHA’s recommendation to ban e-cigarette flavors, including menthol, is concerning because it would “reduce use by smokers wishing to switch, particularly since tobacco flavorings are constant reminders to former smokers of cigarette smoking.”

In conclusion, there is still plenty that we do not know yet about the effects of e-cigarettes and vaping on cardiopulmonary health. Evidence is building and suggests that efforts need to be taken to reduce possible long-term risks, especially for youth and those who were previous non-smokers. The evidence is not nearly as rich as the generations of work done to understand the harms of cigarette smoking. Still, clues taken from that long history help set the framework of the approaches and guidelines needed to protect public health. Although risk reduction is highly recommended, the evidence is still in its infancy. It is crucial to recognize that the science and guidelines regarding e-cigarettes and youth is a challenging process. The key to this process will be balancing the concerns about health risks to youth with the potential benefits of smoking cessation in adults.

References:

Wold LE, Tarran R, Crotty Alexander LE, Hamburg NM, Kheradmand F, St. Helen G, PhD; Wu JC; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Hypertension; and Stroke Council. Cardiopulmonary consequences of vaping in adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published online ahead of print June 21, 2022]. Circ Res. doi: 10.1161/RES.0000000000000544

Fadus, M. C., Smith, T. T. & Squeglia, L. M. The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: Factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 201, 85–93 (2019).

Lyzwinski, L.N., Naslund, J.A., Miller, C.J. et al. Global youth vaping and respiratory health: epidemiology, interventions, and policies. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 32, 14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-022-00277-9

“The views, opinions, and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness, and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke, or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”