For roughly the past 15 years, I essentially have eaten the same breakfast every morning – a bowl of oatmeal with a sliced banana. And every morning, as I wait for the oatmeal to heat up in the microwave, I do push-ups and sit-ups. It has come to the point where my body reflexively moves towards the small area in my living room right after I push the “Start” button on the microwave. This activity takes all of two minutes and is often rather automated. But during busy stretches on inpatient services, these are sometimes the only two minutes of dedicated physical exercise over the course of a long day.

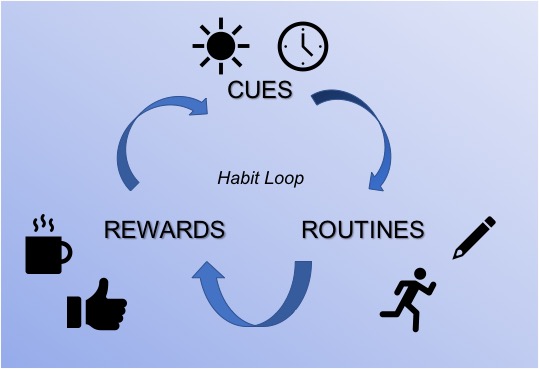

I just finished listening to the audiobook, “The Power of Habit” by Charles Duhigg, and while I never had put much thought into it, I realized my morning ritual is indeed a habit, and just one of many I have throughout my day. In the audiobook, Duhigg expounds on the central role that habits have in our daily lives — essentially comprising a sizeable percentage of our days and forming a large part of our identity. Habits, once formed, become automatic responses to the various triggers we encounter in our day, and often, we carry them out mindlessly. He describes the three components of the habit loop:

- Cue: The trigger that prompts the action. This can be a location, a time of day, a person, an emotional state, or another action.

- Routine: The actions or thoughts that occur in response to a given cue.

- Reward: The physical or emotional satisfaction that results from the habit loop.

The continued repetition of the habit loop leads to a craving for the Reward, which links the Cue to the Routine and promotes the automaticity of this loop.

For good habits, such as my breakfast pushup routine, this can be beneficial and can help structure physical and/or mental well-being or productivity during the day. For bad habits, however, this can clearly be troublesome.

As early career trainees, we often find ourselves complaining that we don’t have enough time in the day to do the things we want to do – exercise, read, write, cook, etc. However, while there are definitely difficult stretches, there are indeed opportunities to do all of these things. And perhaps one effective way is to incorporate them into a habit loop.

For instance, a Cue that everyone experiences daily is waking up in the morning. Consider using this opportunity to link this Cue to the Routine of going for a jog. Reward yourself with your favorite breakfast afterwards (oatmeal & banana, anyone?) or listen to the newest episode of your favorite podcast during the jog.

A particularly challenging habit to develop is giving yourself time to write about your science, as was discussed by senior AHA Early Career Blogger, Bailey DeBarmore, in a recent blog post. Find a way to schedule this Routine into your week by attaching it to a Cue (e.g., Saturday morning) and a Reward (e.g., favorite cup of coffee, checking off that box on your to-do list).

These routines are notoriously difficult to instill at first, and it takes several weeks to develop them into a true habit. But with time, as they become more automated, these good habits become easier to perform. The “Power of Habit” is rife with case examples of the role of habit in our daily lives, and the very brief overview above is just a small sliver of what was covered in the book. However, it inspired me to deconstruct the habits that form my days and encouraged me to re-engineer them into habits that can help me feel better and more productive in my busy schedule as a physician-scientist trainee.

What good habits can you cultivate in this new year?