This past August, the phrase “Representation Matters” commonly graced entertainment and popular culture headlines. Why? In what was ultimately called “Asian August,” several major movies starring Asian-American actors were appearing in theaters, led by the first American film to feature an all-Asian cast in 25 years – “Crazy Rich Asians.” This fervor was inspired by over two decades of under-representation of Asian-American culture in the entertainment industry.

As I am an Asian-American, this particular movement did indeed resonate with me in my personal life. However, I regrettably was not mindful about it in my professional life. Throughout my training, I felt that I had worked with, learned from, and/or befriended men and women of a wide variety of colors, beliefs, and socio-economic backgrounds. Perhaps it was because I was fortunate to train in programs that were diverse, but I don’t necessarily recall reflecting on the diversity nor the benefits of diversity.

In early December 2018, Dr. Hannah Valantine visited our campus at UCLA to deliver our Medicine Grand Rounds lecture, and she was kind enough to meet with many of our faculty and trainees. A renowned physician-scientist and advanced heart failure/transplant specialist, Dr. Valantine is the NIH’s first Chief Officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity. She led an outstanding, eloquent, and (of course) evidence-based discussion on the importance of improving the diversity in academic medicine. She highlighted the emphasis that the NIH is placing on this mission, and the resources her office has developed to not only educate professionals on the issues at hand, but also a toolkit they have created to help promote diversity at our institutions, including how to create a diverse talent pool and perform unbiased talent searches.

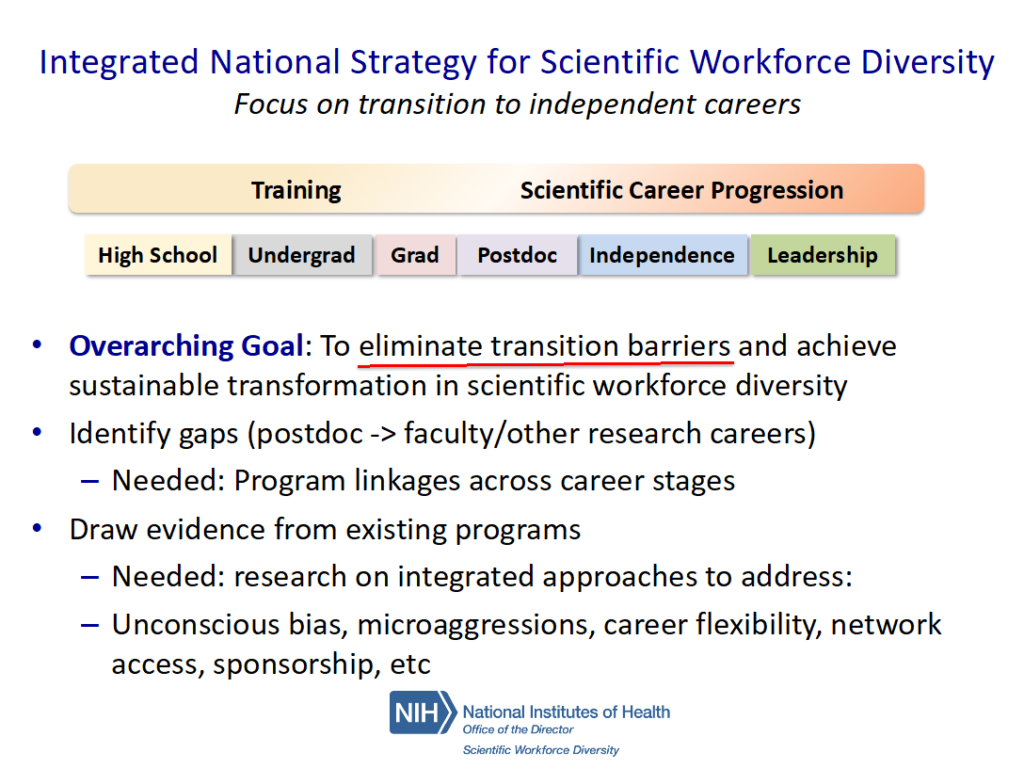

Dr. Valantine presented data showing that while there has been improvement in diversity of trainees early in their training, there remains a significant “transition barrier” for diversity upon entering the junior faculty stage of an academic career (between “Postdoc” and “Independence” in the slide below).

Further, she also mentioned data supporting the improved performance of more diverse groups. In an article from Nature this past year, the subjective and objective benefits of diversity were featured. Interestingly, in an analysis of over 9 million scientific articles, one group found that research “papers written by ethnically diverse groups were cited 11.2% more than were papers written by non-diverse groups.”

With clear reasons for why we should work to focus on a culture of equity and diversity in our scientific workforce, I realized that I will soon be at a stage where I will be choosing the members of my research team. In the spirit of the New Year and with the help of tools provided Dr. Valantine, I have made the following “resolutions” to myself to help prepare myself as I embark on organizing a research team in the future:

- Discover and explore my implicit biases: There are online resources/tutorials on implicit bias, including an excellent one from my home institution, UCLA, as well as tests you can take to discover your own implicit biases. Regrettably, after my first test, I already learned that my results suggested, stereotypically, “a moderate association for ‘Male’ with ‘Career’ and ‘Female’ with ‘Family.’”

- Be mindful of the benefits of diversity when present: Whether in a research group or the team I am rounding with in the hospital, I plan to acknowledge these benefits when present, whether aloud or to myself.

- Follow the NIH Scientific Workforce Diversity blog: It is an excellent reminder of reasons and ways to create an effective & diverse scientific team.

In one of her excellent blog posts from last year, Dr. Valantine wrote:

“Our nation is presented with the unique opportunity of connecting an increasingly diverse talent pool of scientists with the full range of biomedicine careers encompassing basic discovery to health applications, a critical part of the NIH mission to advance human health.”

I am grateful that the NIH has placed high priority on this mission, because indeed, Representation Matters, and in the field of academic medicine, representation can lead to better science and better treatments for our patients.