Big data, machine learning & artificial intelligence — how BCVS19 showed me that basic cardiac researchers needs to take these more seriously.

I had one main goal this year when I attended BCVS19 in Boston: go to sessions I normally wouldn’t.

Basic cardiac researchers, myself included, can sometimes have a very narrow field view. We tend to focus on the workhorse of the heart, the cardiac myocytes. For a long time, other cell types were completely overlooked. Only recently have big conferences, like BCVS19, started to have more sessions focused on the unsung heart heroes like fibroblasts, inflammatory cells and even fat. These are now the norm now, which is definitely how it should be.

At BCVS19 this year, sessions such as “Beyond Myocytes and Fibroblasts: Forgotten Cells of the Heart” and “The Future of Cardiac Fibrosis” provided myocyte-free perspectives that are desperately needed. While I was excited to experience these talks, I noticed there’s another area that is critical to the future of cardiac research that I’ve been overlooking.

The last couple sessions touched on how to handle big data, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) both in basic research and clinical settings.

Based on session attendance, I wasn’t the only one who had been overlooking these topics.

Now, this low turnout could be because these sessions were towards the end of the conference, but I’m not sure that’s actually the case. Either way, I’m glad I decided to make it because I found myself wanting to know more about pretty much everything that was discussed, which is basically the whole point of going to conferences, right?

The “Advances in Cardiovascular Research — New Techniques Workshop” was a panel of experts fielding questions from the audience. I was most struck by the information Dr. Megan Puckelwartz from Northwestern provided about her experience doing human whole genome sequencing experiments. Among many things, Dr. Puckelwartz mentioned that universities need to prepare themselves for the future of genomic research because most institutions don’t have the storage capacity needed for this analysis. The scale of data storage needed is massive, but few institutions are ready. Advances in genomic research are fast approaching personalized medicine becoming a reality, but we can’t harness the power of these experiments if we don’t have anywhere to store the data.

More people should be talking about this and discussing concrete solutions.

On the last day of the conference, on a whim I decided to attend the “Machine Learning, Big Data and AI in Heart Disease” session, which was worth it.

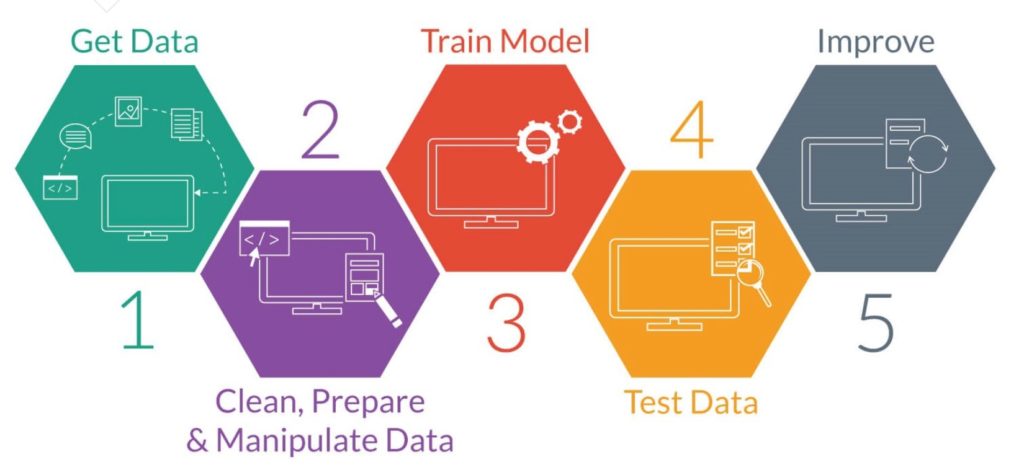

Simplified model of how machine learning works. Source: https://machinelearning-blog.com/2017/11/19/fsgdhfju/

Kelly Myers, the chief technology officer from the Familial Hypertension (FH) Foundation talked about their work focused on creating an algorithm to better diagnose FH patients from their national registry/database called CASCADE. This was desperately needed because even though 1 in 250 people have FH, only ~15% of patients with FH have been identified, mostly because current biomarkers aren’t sensitive enough. With their machine learning algorithm and collaborating with several institutions and physicians, they’ve been able to identify 75 factors that fit into six distinct categories that are predictive of the disease. Looking at lab results alone isn’t enough — more information is needed but this wouldn’t have been understood without a machine learning approach.

Dr. Qing Zeng, the Director of the Biomedical Informatics Center at GW School of Medicine also talked about her AI/ deep learning approaches focused on improving the cardiac field. She mentioned that using deep learning approaches is advantageous due to their ability to model highly non-linear relationships. She also discussed that the main challenge in applying this approach to clinical data is that it’s not a magic pill — clinical data is highly complex. There are many missing values and researchers have to present the data in a way physicians will accept/understand. Because Dr. Zeng’s work was focused on creating a model that could predict if heart surgery was worth it for patients who were deemed “frail”, the cooperation from the cardiac surgeons is key.

When asked “Have you asked surgeons if your score aligns with their opinion about whether a patient should have surgery?” Dr. Zeng responded: “This is tough, we would like to compare what we recommend against what humans expect, but cardiac surgeons aren’t willing to give us a score, so we have a hard time pinning down it actually means to evaluate this against humans.” To make AI/deep learning studies relevant, the researchers and physicians need to figure out how to communicate.

Overall, I learned a lot from these sessions because they highlighted how far the field needs to grow in these areas. Looking forward to BCVS20 next year to see if we’ve figured out a way to work through these growing pains.