AHA Scientific Sessions 2021 was an exciting event with many educational opportunities to gain career development strategies to increase scientists’ productivity and effectiveness at work and in life. As an early career scientist, I often wonder how some of my colleagues, both early career and more seasoned investigators, can be so successful in their ability to publish papers or receive grants while maintaining a perfect balance with their personal lives. In a fantastic session titled “Strategies for Career Success by Highly Effective Scientists”, panelists, including Dr. Elizabeth McNally, Dr. Pilar Alcaide, Dr. Jil C. Tardiff, and Dr. Pradeep Natarajan, shared and discussed strategies that highly effective scientists use to increase efficiencies at work and at home to maximize productivity. This session offered a broad overview of strategies for early career scientists. However, in this first installment, I will present my perspective on leading an effective research lab, which applies to early career investigators (ECIs) in transition periods in their careers. I have detailed several guiding tips towards leading a successful research lab in the following.

Leading an effective team

For many transitioning from a graduate or postdoc role to their first academic appointment, the idea of launching your own lab can bring both feelings of excitement and uncertainty. We know there are many possibilities for success. Still, the path to a well-functioning and healthy lab can be overwhelming. Here are some tips on planning ahead and moving forward with your lab even when resources run low:

Make the most of your resources: Regardless of the resources that may have been available in your lab in graduate school or as a postdoc, opportunities afforded to you in your new environment may be very different, and your expectations may need adjustment. Importantly, before jumping in your work with a team, familiarize yourself with the elements in your new environment that mirror your previous setting and the factors that may challenge the work you intend to do. For instance, your start-up package may not allow you to recruit graduate students or postdocs, but you may find an excited group of undergraduates who may be ready to work with you. Importantly, you should move forward with the resources at your immediate use. Additionally, you may be able to position yourself with new colleagues and their labs to borrow equipment or tools that can help offset your limitations and avoid significant delays in building your lab and moving analyses forward. Finally, remember that both you and your students are on a clock; moving forward with available resources will ensure the success of all parties in your lab.

Recruiting: Choosing the best team will depend on the project’s needs and available resources. With each candidate, carefully read their resume/CV to access their availability timeline, degrees attained, and grades in relevant subjects. At every step of the recruitment process, foster diversity and inclusion to gain the best candidate who can offer a wide range of skills and experiences that can inform the team’s work. References are helpful but limited as the environments that may have garnered success or failure for the candidate in one group may differ in the next. Also, assess the candidate’s strengths and weaknesses, keeping in mind the projects that may be a good fit for the candidate. You may also want to include your team in the interview process with a new candidate and gain oral feedback on how they see the individual fitting with the project needs and the lab culture. Finally, even if a candidate accepts the position, try not to consider the person recruited until they arrive for their first shift. It’s not uncommon for candidates to show enthusiasm at the interview stage but fail to come to start the work. You will also want to be mindful that the first three months of work is a trial period where the new recruit will acclimate to the lab and demonstrate the quality of their work, which may or may not need to be adjusted to the expectations of the lab. This period is an excellent opportunity to learn more about the candidate’s skills and personality, perspectives, how quickly they overcome learning curves and establish fit within the group.

Avoid decision paralysis and get moving: Realistically, a mountain of decisions need to be made when starting a lab. New faculty are thrust into many firsts: first projects, first lab members, first major purchases, etc. Feeling completely unprepared at this level of independent responsibility is the norm. Regardless, the sheer number of decisions can be paralyzing, especially when combined with perfectionist personalities, common among scientists. In a letter to young scientists at Science.org, Somerville et al. recommend that ECIs just need to start doing something to overcome decision paralysis. It is the only way for the lab trainees and its leader to get moving. Additionally, in those moments of doing, you can build realistic expectations about the actual needs of your research and the team and what is feasible to be conducted in a given period. The lab will feel most successful when expectations are checked, and outcomes are realistic.

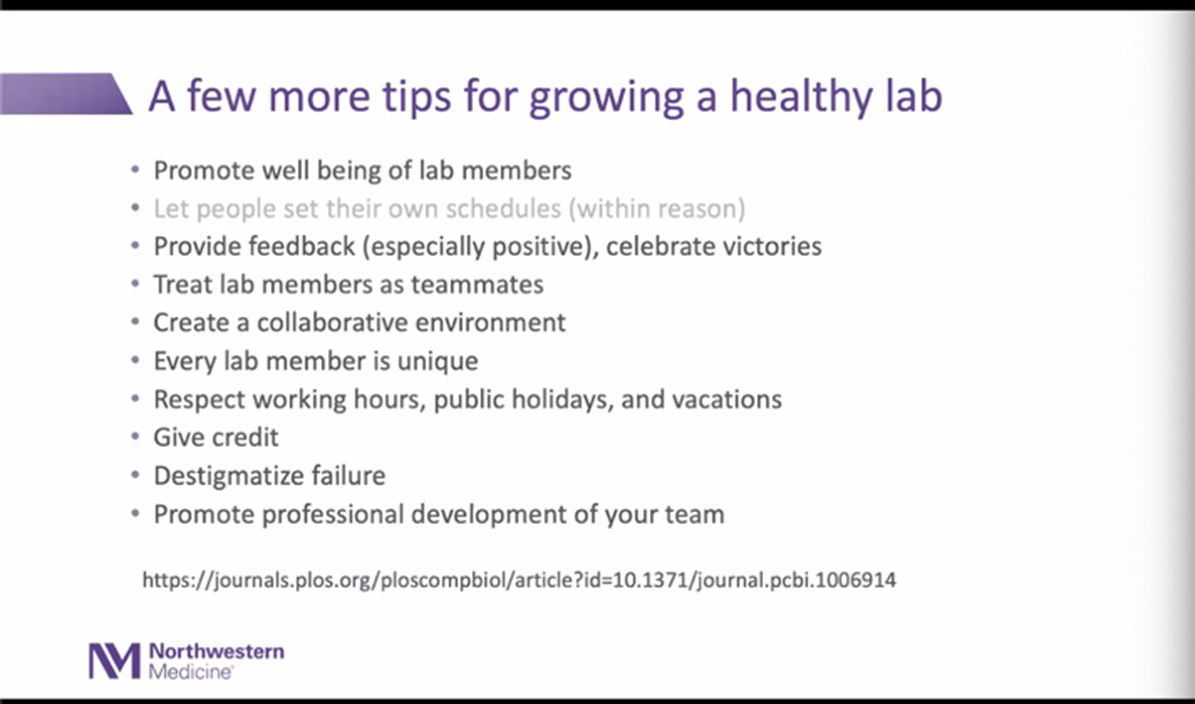

Setting your lab culture: The most successful labs are a product of the brilliant minds that share membership. Importantly, successful labs share a common understanding of how they can be an environment that will generate positive training experiences for all and productivity. Through shared vision and expectations, lab members are made to feel like they belong, that their work is valued, have a sense of autonomy, and know how to succeed. You may have had the opportunity to work with several labs before becoming independent, or you may only know one lab family. Whatever the experience, it is likely there were scenarios where things worked extremely well – you gained hands-on training, communication was well established, feedback on performance was constructive, you felt that your efforts lead to presentations or publications that would support your career advancement — and other experiences that could have used improvement. Drawing on your past experience can help define how you want to manage your lab and the expectations that your trainees expect from each other and you for overall success. At Nature.com, Hagerty et al. wrote about setting clear lab expectations. These could be a lab manual with values and daily expectations or periodic lab meetings discussing lab culture. Topics like socialization, conflict resolution, and inclusions can be presented with a plan for how expectations can be manifested daily. Setting the tone of lab culture should be deliberate and can build on your own experiences. As the leader, you should make your aspirations clear and be a regular example of your team’s expectations. Additionally, with regular assessments, you will notice what works and what doesn’t. You can revise your lab manual and adjust your culture with the inclusion of your team. Dr. McNally also provided some other excellent tips for growing a healthy lab:

Take care of yourself: Last but certainly not least, it’s important to state that while a lab can definitely run on its own (especially if established well), the lab leader must also set means for self-care and feedback. ECIs should utilize their own advisors/mentors to discuss the progress and nature of their labs and do so regularly. You should also engage with colleagues or other individuals outside the lab to discuss problems that may arise and have an external perspective on resolving issues. When something does go wrong, give yourself a break from the situation and allow the matter to breathe and dissipate before coming to firm solutions. Sometimes, firing people will have to happen, and it’s ok to recognize that it is a difficult decision to make. Remember that even as a leader, you are human and have emotions in many of your investments, especially your research lab. Finally, learning to say “No” to opportunities that may overextend or add little benefit to your team and yourself may be the best solution to maintain a healthy and well-functioning research lab.

I hope you found these guides useful for planning and building your future research lab. Perhaps these tips helped improve your current lab. Next time, I will touch on another valuable topic to ECIs and their success.

References:

https://www.science.org/content/article/three-keys-launching-your-own-lab

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07383-0

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”