Written by Isaiah A. Peoples MD, MS, Christy N. Taylor MD, MPH, and Nasrien E. Ibrahim MD

The current climate in America has taken the rose-colored lens off society and allowed the world to see the gross disparities faced by Black Americans and other marginalized groups. Initiated by the multiple murders of unarmed Black Americans by police officers to the unprecedented dissimilarities in the death rate of Black and brown people due to COVID-19. This has given pause to the medical community; forcing us to reflect on the ever-increasing health disparities facilitated by institutional racism, which has sadly been perpetuated in medicine including in heart transplants. This is partially reflected by the low number of hearts being transplanted to people of color even when medically indicated. Often the factors of financial and social “requirements” are what lead to many being turned down for transplantation. These are young patients, Black patients, brown patients, patients with young children, patients without financial means, patients without caregivers, patients neglected in the healthcare system; souls that will haunt us forever. Our healthcare system is broken.

Heart transplantation is one of the greatest innovations in medicine to date. Helping patients with end-stage heart failure (HF) and New York Heart Association IV symptoms have a second chance at life, hiking the Grand Canyon, or keeping up with their young children- nothing comes close. However, along the continuum of HF from the prescription of guideline-directed medical therapies (GDMT) including internal cardioverters defibrillators to advanced therapies including heart transplant, Black patients are undertreated.

Transplant selection is a complicated process where ethics, emotions, and implicit biases occasionally muddle the process further. A study by Dr. Khadijah A. Breathett and colleagues examining racial bias in the allocation of advanced HF therapies found Black women were judged more harshly by appearance and adequacy of social support.1 In transplant selection there are non-modifiable factors as well as modifiable factors to consider, with modifiable factors carrying the greatest risk for bias and inequitable listing and organ allocation decisions. Patients too sick to survive, for example, a patient with multi-organ failure intubated and on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or patients with active cancer have absolute contraindications- these are non-modifiable. Age cut-offs vary across transplant centers, but in all cases, the same standards must be held for all patients to ensure equity.

Modifiable risk factors are where decisions are more likely to be influenced by implicit biases and where the greyest zones exist. When patients are asked to identify social support systems do we consider a group of church members who agree to care for the patient in a rotating fashion adequate support or does a family member or partner need to be identified? What about patients with insurance but limited finances to the extent co-payments are unaffordable? Do we expect patients to fundraise or does the transplant institution assist in some costs for a prespecified number of patients each year? Do we expand insurance coverage? What about undocumented patients, patients without insurance, and patients in prison? What about patients with substance use disorders? Are we morally obligated to assist them to ensure future transplant candidacy? Modifiable is where things get murky.

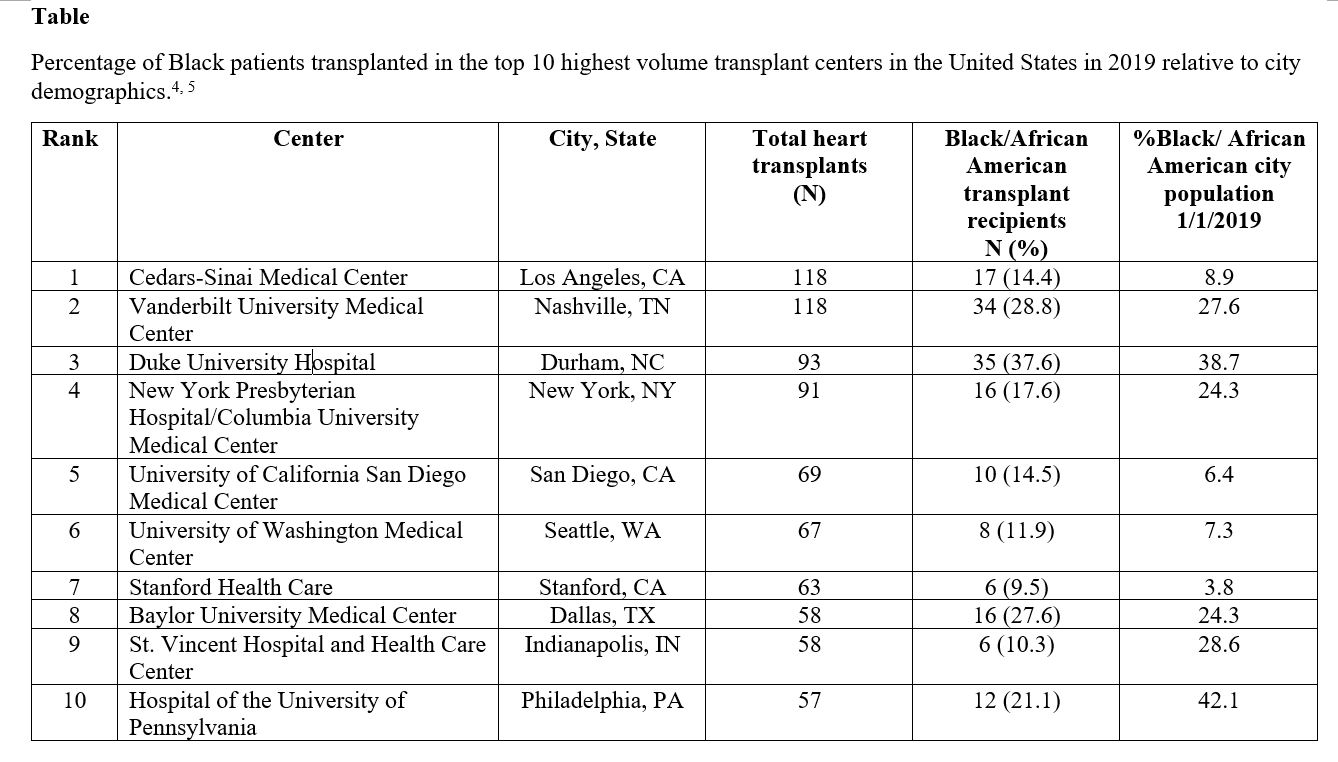

We wanted to examine the percentage of Black patients who received heart transplants in the highest volume transplant centers in the United States relative to the demographics of the cities where these transplant centers reside; we looked at 2019 data for sake of completeness (Table 1). We recognize this is merely a snapshot in the history of transplant programs from a bird’s eye view, that cities may have multiple transplant centers, Black patients may prefer certain centers, and finally, the city demographics are from 7/1/2019 and may differ if we had year’s end demographics. HF is more prevalent and is associated with higher mortality and morbidity in Black individuals than in white individuals2 and once it has developed, Black patients have more events and worse health status compared to white patients. As such, the proportion of Black patients transplanted at each center should in theory at the very least match demographics of the city where the transplant center is located, but without granular data, we cannot be certain.

What we are certain of is the need for improving the care Black patients with HF receive. The first and most important is earning trust amongst Black communities and reestablishing the doctor-patient relationship through community engagement. This will allow us to inform Black communities about the transplant process and when a transplant should be considered and what to expect. We must develop GDMT optimization programs in Black communities to reduce morbidity and mortality, identify patients who need device therapies, and identify those who do not improve and require evaluation for transplant earlier since Black patients are sicker when listed and more likely to die waiting with longer wait times.3 Additionally, transplant centers should be tasked to develop outreach programs to Black, Hispanic, minoritized, and marginalized communities and perform a prespecified number of transplants in patients who lack financial means based on transplant center volume. Implicit bias and antiracist training for all team members involved in transplant selection must be required and transplant selection teams must be diversified by concerted efforts in hiring diverse faculty but also improving the diversity of the pipeline. And for modifiable factors, rigorous efforts such as substance treatment programs and involvement of weight loss clinics must be attempted consistently with our moral obligation to assist patients in becoming eligible for transplant.

Heart transplant is one of the most incredible things in medicine, we must ensure it is accessible to all by dismantling the oppressive systems in place that have made access to organs inequitable. Black Lives Matter in Heart Transplant Too.

References

- Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Yee RH, Knapp SM, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera-Theut K, Zabala L, Stone J, McEwen MM, Calhoun E and Sweitzer NK. Association of Gender and Race With Allocation of Advanced Heart Failure Therapies. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3:e2011044-e2011044.

- Sharma A, Colvin-Adams M and Yancy CW. Heart failure in African Americans: Disparities can be overcome. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2014;81:301-311.

- Lala A, Ferket BS, Rowland J, Pagani FD, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Horowitz CR, Pinney SP, Bagiella E and Mancini DM. Abstract 17340: Disparities in Wait Times for Heart Transplant by Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Circulation. 2018;138:A17340-A17340.

- United States Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 accessed 12/20/2020.

- United Network for Organ Sharing https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/center-data/ accessed 12/20/2020.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”