In Part 1, I shared common experiences between myself and other BIPOC physicians in medicine and cardiology. In this piece, I will dive into the importance of why increasing diversity and inclusion in cardiology is so urgent. Cardiology is a coveted specialty and can incentivize a power dynamic that does not often include BIPOC. I would argue that for a progressive program, creating an inclusive workforce will help programs progress, be innovative, and positively impact patient care in the community. This change will be a win-win for all.

When reflecting on this topic, I am reminded of an African American woman who was crying on the cath table the other day, with a look of fear and helplessness. This was not long after a report of a physician of color, who was infected with COVID19, reported that her symptoms were dismissed, and later died. If a physician feels unheard, how can a woman of color who is not a physician feel safe? The cath team did a great job of comforting her, but it was hurtful to see her in such fear.

African Americans are significantly affected by heart disease risk factors; in fact, together these conditions contributed to >2.0 million years of life lost in the African American population between 1999 and 20101, with heart disease being the leading cause of mortality in African Americans. Unfortunately, there is a lack of African Americans in the physician workforce considering African Americans make up ~ 13% of the U.S population, but only 4% of U.S. doctors2. According to the Harvard Business Review, increasing the numbers may improve health outcomes. They described a study in Oakland that assigned African American male patients recruited from barbershops to African American and Non-African American physicians. What they found was that African American patients were more inclined to agree to more invasive and preventative services than those with non-African American doctors. This is not an argument for a segregated system, but certainly increasing the numbers and learning from colleagues can help BIPOC patient outcomes.

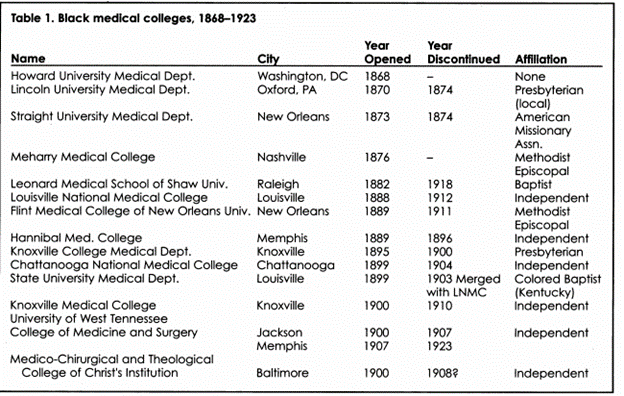

One historical change in medicine that impacts care in the African American community is likely rooted in the Abraham Flexner Report3. An African American medical student applying to medical school in 1900 had 10 choices which declined to approximately a quarter of that by 1920. The Flexner Report, which was meant to trim the medical workforce to only those with the greatest quality of training, decided that only two medical schools that trained African Americans (Howard University and Meharry Medical College) were worthy of staying open. His devastating comments terminated the rest4. My cousin, Dr. Hubert Eaton, wrote about this dilemma in his book Every Man Should Try5. He graduated from the University of Michigan School Medical School in 1942 and his father went to Leonard Medical School (see Table 14). He found his father’s exam scores and noted they matched his own. He was perplexed that Leonard was shut down and he wondered: Who validated the Flexner report? Why was one individual able to create this modernity in medicine without any scrutiny?

By building diversity and increasing contact between those who have shared experiences, the field of cardiology could improve BIPOC patient trust and compliance as well as reduce cardiovascular disease outcomes. This change could lead to lower hospital admissions and increase prevention efforts. Many BIPOC is inspired by giving back to the community and being involved in community engagement. This community service is via BIPOC oriented organizations (e.g., The Divine 9 fraternity and sororities, the Boule, The Links, Incorporated, etc.) as well as the Black Churches. As BIPOC cardiologists, we have the ability to teach important primary prevention to thousands of people and the message is stronger if that provider looks like the community they represent.

Cardiology is a prestigious field and as such should aim to set an example for leadership across the country. We know that inequities exist in all aspects of cardiovascular disease and one way to combat this issue is to build a diverse workforce. When we lost community physicians after the Flexner report, we lost the community itself; the field of cardiology has the resources to restore this relationship and improve heart disease outcomes.

References:

- Carnethon et al. Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017: 136(21)

- Research: Having a Black Doctor Led Black Men to Receive More-Effective Care by Nicole Torres. Harvard Business Review 2018

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Science and Health Publications, Inc.; 1910.

- Savitt. Abraham Flexner and the Black Medical Schools. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006: 98 (9)

- Every Man Should Try by Dr. Hubert Eaton

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”